Quest’articolo è tradotto in italiano qui: https://tavolamediterranea.com/2020/05/08/baking-with-the-greeks-demeters-daughter/

Este artículo también está traducido al español aquí: https://tavolamediterranea.com/2020/06/13/horneando-con-los-griegos-la-hija-de-demeter/

The following post contains some naughty words, references to potentially naughty activities, and depictions of battle violence taking place on top of loaves of bread. Viewer discretion is advised.

There are many things in this life that make me happy, such as: dogs; coffee; pancakes; archaeology; a Deadmau5 concert; and reading in bed. Then there are things in life that compel and intrigue me, such as: bread; boats; and rabbit-holes… The first two subjects are understandable as we all like bread and we all have Dads who taught us to love marine exploration and shipping history,… but the last subject is fun for some but not for others: The research rabbit-hole. It’s the deep, dark tunnel that you go down when you start a simple conversation with someone about something… and then next thing you know it’s 2 am, you’ve got every book that you own open on the floor, and all of your archaeologist, linguist, and historian friends are blowing up your WhatsApp. A rabbit-hole is something that many academics, obsessives, and other ‘need-to-know-now’ folks go down when researching something obscure or trying to understand something completely. Sometimes we arrive at conclusions and other times we find ourselves no further along, unbathed and unfed for a week, sleeping in a pile of books. It often causes one to miss dinner or forget about social engagements… but in the end it’s a learning experience and boatload of fun! And this is exactly what happened a few weeks ago when my friend and fellow bread-nerd, Mordechai, contacted me with a query about a passage written by Dr. Joan M. Frayn — one of the most respected 20th century academics to have written about Roman farming, baking, and agriculture.

In her paper titled: “Home-baking in Roman Italy” (1978), and in reference to a so-called bread-roll, Frayn makes the following statement to explain how some Graeco-Roman breads were embellished or formed into sections before baking:

“The indentations could be made with the fingers, as Athenaeus (III, 108c) says that the lines were made on certain bread-rolls, with a knife, or with a reed, which Columella recommends for slicing fruit and vegetables and Apicius for cutting up foie gras.“

Joan M. Frayn, Home-baking in Roman Italy, pp. 32

Now this is a valuable paragraph in that it references what ancient Romans used to cut or portion foodstuffs with in the absence of a knife… but I think the manner in which Frayn structured this sentence sent us spinning for a bit, as originally we had thought that Frayn was inferring that the bread-roll she was referencing from Athenaeus (III, 108c) was also embellished using a reed. Alas, it was not the case and perhaps Frayn is simply missing an ‘or’ between the words ‘rolls’ and ‘with’. But the rabbit-hole didn’t stop here. I wanted to dig in to the actual text from Athenaeus (III, 108c) so I could get to the bottom of this ‘roll’ that Frayn was talking about. Once I dove into the original ancient Greek text further, in an effort to explore its relation to bread-making fully, and called in some archaeologist friends with experience in translating ancient Greek to cast an eye,… we were collectively off and running through a wonderful rabbit-hole that would result in a pretty good head-scratcher and today’s post and bread recipe.

Welcome to the Rabbit-Hole:

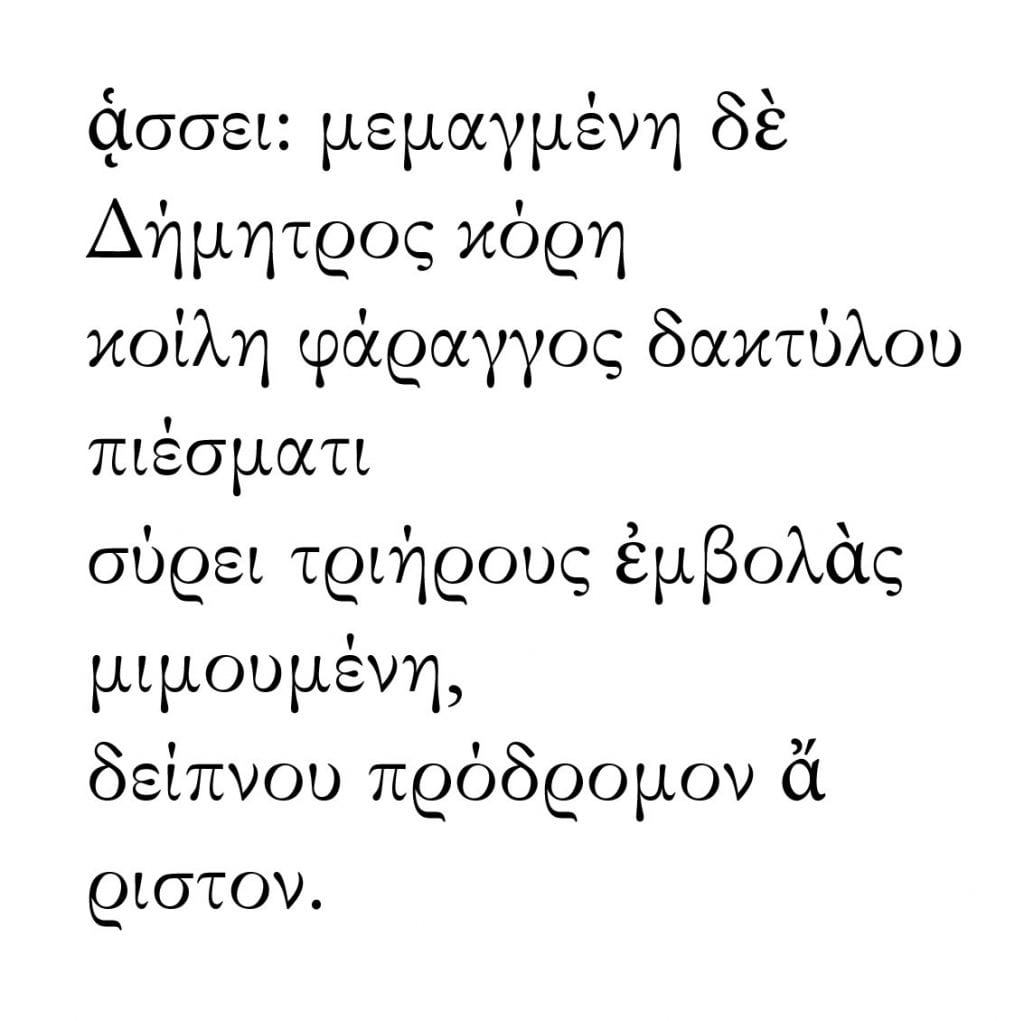

Let’s start by looking at the passage that Frayn referenced in Athenaeus (III, 108c). This is the passage in ancient Greek:

Initially, I ran each word through an online translator, both for Greek and ancient Greek, to see what words would jump out of the passage. In Gooogle translate, it looks like this:

“It is: drunk D Demeter’s daughter Hollow finger canyon pressing draws three embossed imitations, Dinner forerunner Friston.”

Haha! Oh dear… While there are some words that made sense, others did not translate well as is often the case with Google Translate. As I am not experienced whatsoever in reading ancient Greek, I called on archaeologists, Michael in Athens, Tiziana in Sarno, and Classical-era art preservationist, Jose in Barcelona, to cast an eye along with me to tell me what they got out of this passage themselves. While I left them to break the passage apart in their own cities, I searched online and in my books to see if there were any existing English translations that corroborated Frayn’s statement. On Bill Thayer’s Web Site (one of my favourite resources!)… we find the following translation, which is sourced from the Loeb Classical Library’s 1928 publication on this fragment:

“The kneaded roll, Demeter’s daughter, draws its hollow cleft along, made by the pressure of the finger to look like a trireme’s ram — the best introduction to a dinner.”

The Deipnosophistae of Athenaeus, Loeb Classical Library edition,

1928

Okay. This translation references a roll too… Perhaps this is where Frayn got her translation? Then I found this translation of the fragment which supports the assumption that the passage is in reference to a grain-product of some variety:

“Then comes the daughter of the bounteous Ceres, Fair wheaten flour, duly mash’d, and press’d Within the hollow of the gaping jaws, Which like the trireme’s hasty shock comes on, The fair forerunner of a sumptuous feast.”

The Deipnosophistae of Athenaeus – Delphi Complete Works of Athenaeus (Illustrated) (Delphi Ancient Classics Book 83), 2017

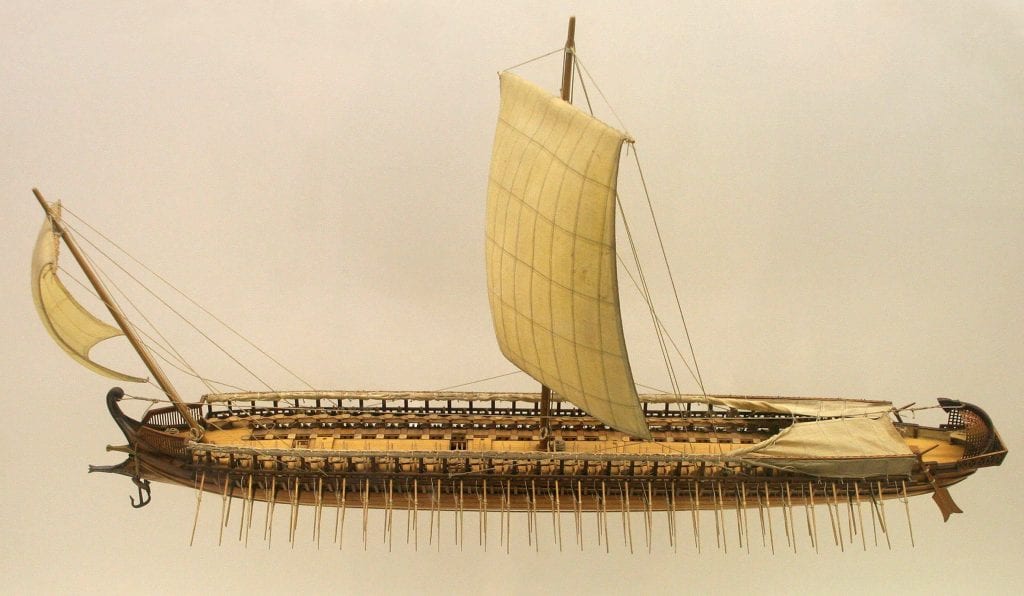

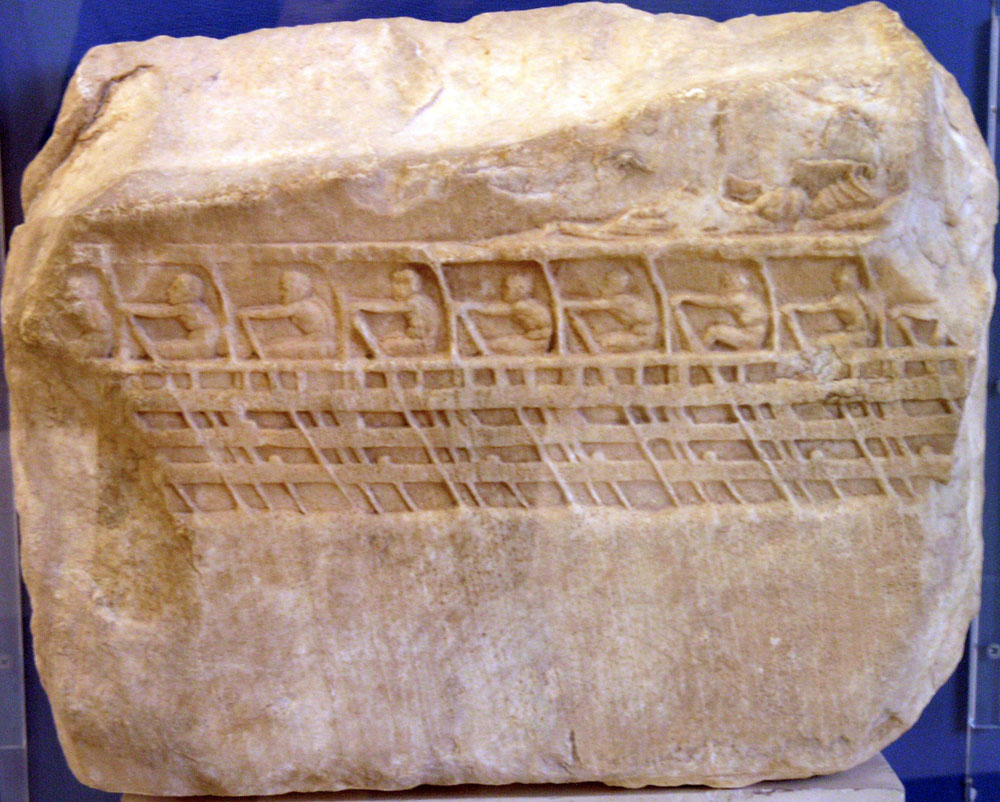

Hmm. Okay. The latter translation seems to be more elaborate than the first with all of its talk of bounteous Ceres, gaping jaws, and hasty shocks… And it appears that in this translation we have reference to kneaded flour and a fast-moving trireme: the man-powered warships used by the Greeks during Classical Antiquity!!! … Sounds like bread and boats to me, doesn’t it?… Yessiree! These were my exact initial thoughts when I flew out my chair and set out on a wild and crazy baking spree, baking loaf after loaf of a Graeco-Roman bread typology that was painstakingly shaped to resemble a trireme. But the rabbit-hole didn’t stop here.

As I was kneading away, Michael and Jose then responded and said, respectively, that they felt that the passage in Athenaeus (III, 108c) reflected statements such as: “The daughter of Demeter, wide chasm, uses a finger and drags the cleft to the ram of the trireme“; and “Demeter’s daughter, draws a trireme in relief by pressing the hollow cleft with the finger.” There was no mention of bread or rolls in their messages… just boats and fingers. How odd.

So, I then ran the passage through an ancient Greek online dictionary resources myself and I came up with this, with my own insertions in brackets:

“It is: Drunk Demeter’s Daughter (Kore/Persephone) hollow canyon finger press draws trireme embolus/blocker (ram) imitation; excellent precursor to dinner.”

Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, (III, 108c) (Translated through perseus.tufts.edu and Google Translate)

What?? … and I struggled to find a definitive reference to bread. And then Tiziana emailed and said that she read the statement as: “The girl of Demeter drags with the pressure of her finger a deep crack, which imitates the charge of a trireme.” Tiziana felt that the phrase was alluding to something sexual. Oh oh. Perhaps this passage is a bit more complicated than we had originally thought. This was somewhat vindicating to me, in a strange way, as four hours earlier, in the midst of my baking spree and before I received the email response from Tiziana, I had messaged a photo of one my test-loaves to an archaeologist friend, Cristina, with concerns surrounding the suggestive appearance of the loaves:

Okay. Calm down. I’ve already snuck a penis onto a loaf of bread on this site before. A vagina was bound to happen at some point, to be certain… And besides, Mordechai pointed out that the ancient Greeks also made a loaf of bread shaped like a phallus called olisbokollix… So let’s go down this rabbit-hole a little further, shall we? Why don’t we take a closer look at the section of text translated into English to see why Tiziana felt this way about the passage.

When we look at the context of the entire section of the Athenaeus (III, 108c) passage, as seen on Bill Thayer’s page’s interpretation below, for example, we can see that there is a bit more to this passage than the literal translation of the III:108c passage alone… something perhaps a little bit naughty in nature, as Tiziana suggested:

“Fish for frying are mentioned by Alexis in his Demetrius as well as in the play cited above. Compare Eubulus in Orthannes: ‘Every pretty woman who is in love resorts thither, as well as the runty lads who are nurslings of the frying-pan — wild Mohawks lounging in the cake-shops. In the same company, too, the squid and the maid of Phalerum, wedded to lambs’ entrails, skip and dance like a colt let loose from the yoke. The fan stirs up the watch-dogs of Hephaestus, rousing them to fury with the hot vapour from the pan, and the savour thus provoked leaps to the nostrils. The kneaded roll, Demeter’s daughter, draws its hollow cleft along, made by the pressure of the finger to look like a trireme’s ram — the best introduction to a dinner.“

Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, III, 108b, c

There’s something suggestive in those words indeed, but this isn’t the only way to interpret this fragment and we may not yet be seeing how all of these words work together in ancient Greek either… so let’s take another step back and get to the KORE of the issue.

Kore (also known as Persephone) is the Greek goddess of vegetation and grain. She is mostly associated with grain and is often viewed as the embodiment of it. Kore is referenced in the ancient Greek passage in this manner:

And on it’s own, these four words translate roughly to: “mix of Demeter’s daughter (Kore)“… and this is where we see the idea of ‘bread’ begin to take shape. This word below:

translates to the Greek word ” Memagmeni“. ‘Memagmeni/Memagmenon‘ translates to ‘Maneggiare‘ or ‘Impastata‘ in Italian. These two words translate to knead/kneaded in English. When we look at the phrase “mix of Demeter’s daughter (Kore)” we can now understand it to mean something similar to: “Kneaded Kore” which effectively means kneaded grain, but not necessarily a kneaded bread-roll. But the rabbit-hole doesn’t end here! I still think there’s more to this ‘Kneaded Kore’ conundrum than just dough shaped like a Greek warship….

We are reminded that Demeter is the Greek goddess of agriculture, annual cultivations, and harvests. Her Roman name is Ceres, which is why your morning bowl of Puffed Wheat is called CEREAL! The Homeric Hymn to Demeter (650 BC) tells us that Kore (also known as Persephone) was the daughter (the product) of Zeus and Demeter. Zeus being the god of the sky, thunder and rain; and Demeter being the goddess of the harvest. Kore is therefore assumed to represent wheat itself, or the wheat seed, that is planted and harvested annually. Kore was the abducted wife of Hades, the king of the underworld, and she was made thus one day while out innocently gathering flowers with her besties. She was damned to live permanently underground, in the dirt, until Zeus had it out with Hades and demanded that Kore come up out of the underworld as her mother, Demeter, had been so depressed after her abduction that famine had ensued all over the land. But because Kore had ‘sinned’ and had eaten pomegranate seeds while hanging out under the dirt with Hades (sounds a bit like Eve taking a bite of the fruit of knowledge after the serpent told her to do so…) Kore was only permitted to come up for two-thirds of the year, during planting and harvest, only to disappear again during the fallow months leaving the dirt barren. As Demeter was satisfied to see her daughter for two-thirds of the year, according to Greek mythology, she established a system of rituals at Eleusis called the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Let’s talk about the Eleusinian cult now. Demeter and Kore were the principal goddesses of the Eleusinian cult. The Eleusinian Mysteries (rites or rituals) were performed annually in Eleusis (near modern-day Elefsina, Greece) prior to autumn wheat-planting and were meant to mimic the annual cycle of the planting, harvesting, and ‘wintering’ of the wheat-fields through the re-enactment of the myth of Kore’s abduction. The earliest archaeological evidence depicting the Mysteries date to the 5th and 4th centuries BC.

Part of the autumn planting process involved the first-ploughing and preparation of the fertile earth for planting. Ploughing was necessary to open the earth again so that the seed may be planted and Kore will rise from the underworld once again. When we think of a ploughman as he is preparing the earth for the seed, what exactly is the plough doing to the earth? It is dragging a hollow cleft along until it reaches a point where some of the earth it is displacing is piled up at the head of the plough leaving an elevated mound of dirt at the fore of the cleft that it has hollowed out, much like the bow of a trireme. The earth is opened by the plough… within the hollow of the gaping jaws, Which like the trireme’s hasty shock comes on. The ploughman then drops the wheat seed into the cleft in the earth, in anticipation of the arrival of Kore once again when the wheat crops come in from this planting.

According to Mara Lynn Keller (1988) the Eleusinian Mysteries were rituals that did indeed carry strong overtones of sexuality and fertility. Keller refers to the following line in Homer’s Odyssey that draws a very clear connection between ploughing, sex, and fertility:

“…when fair-tressed Demeter, yielding to her passion, lay in love with Iasion in the thrice-plowed fallow land…”

Homer, The Odyssey, 8th c. BC

Are you thinking what I’m thinking? I think this loaf of bread, Demeter’s Daughter, has more to it than simply being a ‘kneaded roll’ or a loaf of bread that is shaped like a Greek warship. I think the manufacture of this loaf, and the Greek text used to describe its manufacture, may be a triple-entendre… One that alludes to bread-making, female genitalia and sexuality, and the sexual symbolism behind ploughing and fertilizing the land in ancient Greece.

So with that rather lengthy and winding run through the research rabbit-hole, why don’t we come up for air for a spell and make some ‘Kneaded Kore’ ourselves? I’d say by now you’re probably feeling a bit hungry! So strap the donkey to the rotary-mill and fetch a pail of water… here’s what you’re going to need:

Baking with the Greeks: Demeter’s Daughter

Ingredients (for 2 loaves):

- 4 cups / 600 gr of white (refined) flour

- 4 cups / 600 gr of whole wheat flour

- 1 cup / 235 ml of bread starter

- 3 cups / 700 ml of tepid water

- 2 tbsp / 20 gr of honey

- 3 tsp / 15 gr of salt

- Semolina flour for dusting

Preparing the dough:

- Combine the starter, water, and honey in a large mixing bowl and whisk it together to fully dissolve the starter and honey.

- Add the flour and salt together and combine it quickly so the salt disperses evenly.

- Add the dry ingredients into the liquid and begin mixing it together. Transfer to a clean work-surface to knead the dough until it becomes a cohesive mass.

- Cover the dough with a damp rag and let it rest for a few hours or until it doubles in size.

- Once the dough has rested, uncover it and cut it into two even portions.

- Dust a clean work-surface with semolina flour.

- Gently stretch and fold each portion of dough for a minute or two, or knead the dough to give it a bit more structure.

- Working with each half now: Gently flatten and elongate each half into an oval form, using your hands. The ends of the oval will be the bow and the stern of the ship.

- Roll each of the long sides of the oval gently towards the centre of the loaf; This creates a natural cleft down the centre that you can work further as you form the loaf into a trireme.

Forming the loaf:

- Pre-heat your oven to 200 C / 400 F / Gas Mark 6.

- Dust each loaf with semolina.

- Create the cleft in the dough (which is the hull or the walkway above the hull of the ship), in the fashion that the ancient Greek text says: ‘draws its hollow cleft along, made by the pressure of the finger to look like a trireme’s ram‘…

- To create the hull and stern of the ship, and something that resembles the ram, pinch the ends of the loaves into long, flat points.

Preparing to Bake:

- Transfer the loaves to a baking sheet or a baking stone.

- From here, you can trim the ram (bow) and the stern of the ship with kitchen scissors to give it a blunter edge.

- Take whatever you have lying around the kitchen that’s small and can withstand the heat inside the oven. Use it to prop up the stern and the bow of each loaf. Your bow should be higher than the stern. I used a cookie cutter and a measuring cup to act as supports during the baking or my trireme loaves.

- Bake for 45 minutes until the loaves are medium brown in colour and the crusts look solid and crunchy.

- Let them stand and cool for a few hours.

- Serve with olive oil, honey, robust red wine, sweet white wine, fresh cheese, or strong-flavoured aged cheese.

The end result of this recreation of Demeter’s Daughter (or Kneaded Kore) was a crunchy-crusted loaf with an airy crumb that proved that the rolling technique used to form the sides of the trireme allowed for a fairly even distribution of air-pockets in the loaf’s crumb. The texture was phenomenal resulting in a tough, crunchy crust with a soft, spongey crumb. The flavour of the loaf was hearty, nutty, and well-balanced between the honey and salt. The hint of honey gave it a warmth that was delightful when accompanied with fresh cheese, a strong aged cheese, or a robust red wine.

Furthermore, the consumption of this fine loaf of Demeter’s Daughter was made all the more enjoyable by my friends and I as we discussed the various takes and interpretations of the fragment in Athenaeus‘ Deipnosophistae that inspired this post… and the research rabbit-hole that it took me down for several days. There is great joy to be found in exploring and interpreting symbologies in the Graeco-Roman world be they scratched onto the wall of a taberna or pressed into the top of a loaf of bread… Interpretation is like the wizard behind the curtain of perception forming our ideas, our responses, and our theoretical frameworks from which we will interpret the world around us. Interpretation is in the eye of the beholder. It is the result of the various lenses we use to see and understand objects, landscapes, and texts in the present and in the past. Our families, backgrounds, upbringing, cultures, political and religious affiliations, gender, education, and philosophical leanings all affect the way that we perceive and process the world around us. And this is what makes interpretation and rabbit-holes like this one so much fun… and such an incredible learning process as well. For when we’re open to discussion and exploration, from starting with an initial question about a reed to going down the research rabbit-hole together to explore a passage about bread shaped like a trireme, we have an opportunity to learn a great deal, not only about ancient Greek bread forms or sexual symbolism in ancient Greek food culture, but about each other as well. And then when all the serious archaeological and historical interpretative debate is over and done with… we can get out our Greek warrior miniatures and play Battle of Salamis with our left-over trireme! Ramming speed!

Thank you for reading along and keep cooking it old school!

Join in the discussion! Come on over and follow Tavola Mediterranea on our Facebook page, Twitter, or Instagram. You can also leave a comment about this recipe below on this page. If you’d like to chat in person with me or about any of the other recipes, you can join me at one of the The Old-School Kitchen live events taking place at a museum or venue near you. More information about this year’s events can now be found on the Events Calendar page.

Are you familiar with Adjarian khachapuri from Georgia (the one in the Caucasus)?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JH2a45S8408

The 2 ways shown of making the shape are different from yours, but there is a similar boaty/sexy vibe to it.

No, I was not. But this looks amazing! Thank you for sending this! It’s proof of continuity! – Farrell

A very interesting article Catherine. Your loaf is very similar to the classic Portuguese bread roll known as ”papo seco”. I would love to say this translates as ‘dry breast’ but in this case ‘papo’ means crop/gullet. These rolls are usually made with ‘maminhas’ at each end which does translate as ‘nipple’, so maybe there is a sexual reference after all. Philip

I just discovered your blog, and have been indulging in ALL THE ARTICLES! It is wonderful, unique and so well done. Thank you!. Just wanted to note, that a similar bread still exists in Greece, it is called ???????? (pain-eer-lee), it has the very same boat structure, but it is filled with goodneess. <3

Yes! We had a great chat about this on the Facebook page after the post was originally posted. It’s beautiful to see these traditions still visible in Greek baking. https://www.facebook.com/tavolamed

– Farrell

They look like the Peinirli boat shaped delicacy, although the peinirli are filled with cheese (and in modern variations with other things like bacon etc etc). These were mostly part of the Minor Asian Greeks cuisine.

Yes! We had a good chat about this on the Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/tavolamed after the post was originally posted. Greek baking traditions are a beautiful thing!

Coming to this late, but it looks like a vulva, not a vagina. Simplified, vagina is inside, vulva is the outside parts. That bread looks amazing either way! (The things you stumble upon on the internet whilst looking for ancient Greek recipes for your home educated kids to make! 😀 )

You’ve got a point. 🙂 – Farrell

Really interesting and thank you for your work. Professors always said that the Eleusinian mysteries along with others were a complete mystery. That there are no written records that describe exactly what was practiced except by fragments such as harvest festival, or something to do with rebirth in spring or bloodletting of bulls etc. what you found in your journey makes sense and it is quite interesting. I don’t think there are any descriptors in Latin either of any of the mystery religions. Am I wrong?

You’re not wrong, and there’s a reason for that. Those who were initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries took fearful oaths to never speak of what they saw or heard, and to do so was punishable by death throughout the classical world. In Athens, a war hero who had a youth (IIRC) carrying a basket of fruit and playing a flute at a party was banished, because it was judged to be too close to some part of the Mysteries.

The secret, forbidden-to-be-spoken-of nature of religious mysteries is the cause of the modern definition of mystery.

This is your best post yet! It was wonderful to follow your leaps of intuition and deduction, and the accompanying photos were well chosen. I only wish that I had a working oven so I could taste the loaves myself,

Thank you Catherine! I was down this rabbit-hole for a good week or two so I am glad it worked out well in the end. 🙂