Hey, good looking! Whatcha got cooking?

So… I took a break this week from preparing for this summer’s presentations and cooking workshops in Italy to get back into the kitchen where I could indulge in what I call ‘procrastibaking‘. This sometimes happens when I have a writing deadline or lot of laundry to fold; I decide that my time would be better spent baking ornate loaves of bread and that the work can wait. On most occasions, the procrastibaking pays off, though, and this week it certainly did.

This week I made Christian Orthodox holy bread “Prosphora” for the first time and it was a wonderful experience. You see, last weekend was Orthodox Easter and you would have to have been camping in a cave with no WiFi to miss the pageantry and festivities taking place both at your local Orthodox churches, and online, in honour of this annual religious holiday.

“Prosphoron” is the Greek word for the “offering” of leavened bread that is used in Orthodox Christian (Ukrainian, Russian, Armenian, Serbian and more) and Greek Catholic (Byzantine) liturgies. It is the focus of the Divine Liturgy for Easter Mass. This leavened holy bread, which differs from the western Catholic tradition of unleavened host, is comprised of two different slabs of dough which symbolize the dual nature of Jesus Christ: human and divine.

Prosphora, as plural, are prepared methodically in chronological steps that require cleanliness and include prayer throughout the kneading and rising processes. Sometimes the loaves are prepared domestically by women and sometimes they are prepared at the churches themselves by a designated member of the clergy. Once they are offered, the loaves are cut into sections by the priest during mass and these sections symbolize The Lamb (of God); the angels and saints; the faithful, and the Theotokos — the Mother of God.

Easter, and the Resurrection of Christ, is one of the most important religious celebrations for both the western and eastern Christian churches and the rites surrounding this pivotal day in their respective liturgical calendars involve — you guessed it — bread. And I’m sure it doesn’t take a rocket-scientist among you to figure out why I am interested in making Prosphora and exploring its history a bit deeper. It bears a morphological resemblance to something that is near and dear to my heart: the Graeco-Roman Panis Quadratus (Kodratoi).

I have always been curious about Prosphora and its familiar form and I am doubly as curious as to how it was actually made during the Late Roman period through to the Middle Ages. Many a baker and theologian have proposed that Prosphora is a direct Byzantine descendant of the Panis Quadratus, which we have many a physical example of from the 1862 excavations of the Bakery of Modestus at Pompeii, but is there any way to test this theory?

In a recent exchange with one of my readers, a fellow bread-enthusiast named Mordechai Honig, we discussed the image below. It is clear from this Roman sarcophagus relief that the typical ‘Panis Quadratus‘-style sectioned loaf, that we recognize from Pompeiian archaeological settings dating to 79 AD, had certainly made its way into iconography that depicts Christian events, such as The Last Supper, by the 3rd century AD. But is there a connection between Prosphora and the Panis Quadratus when it comes to production and form? Can we prove that Prosphora are derived from the Panis Quadratus, which is a form that is represented in both Roman and Greek archaeology, and can we state for certain that the two loaves were made in the same way and continue to be made this way today? There’s only one way to find out: experimental food archaeology (with some procrastibaking thrown in). Let’s bake some bread, shall we?

Baking with the Greeks: Prosphora

Ingredients (for 5 small loaves):

- 10 cups (1.5 kg) of white all-purpose flour

- 4.5 cups (1L) of tepid water

- 1/2 cup of leaven

- 1 tbsp salt (optional as some Orthodox churches don’t use it)

- Semolina flour or wheat bran for dusting

Preparation:

*A note to Orthodox readers: I did not prepare my loaves in a religious or ritual fashion as I am not Orthodox. I prepared these loaves to study their history, their role in the liturgy, and their production and form. No disrespect intended. As a Catholic, I’d support leavened holy bread too. 🙂

1.Begin by feeding your leaven (bread starter). It’s advised that you do this the night before you prepare the bread. Note: You shouldn’t use active dry yeast for this recipe as it’s typically frowned upon for this process as the ingredients should be as true to their original form as possible. You can buy starter from your local bakery or try making your own as well. Once your starter has been fed and activated, you can begin to prepare the Prosphora dough.

2. Add the leaven into a large mixing bowl and mix it into the tepid water with your fingers. Slowly add in the flour and salt (optional) and mix the dough with your hands until it forms a well-mixed mass. Cover with a damp tea-towel and let stand until it doubles in size.

3. Using a scale, pull off pieces of dough that weigh approximately 250 grams each. Each slab will be comprised of dough of this weight and you should have approximately 2.5 kg of dough in total. Using semolina flour or bran on a dusted surface, stretch and fold each portion of dough and form it into a round slab of dough. Fold any imperfections or seams under the loaf as you work the loaf into a round slab. Do the same with all ten slabs. Rest each slab on a well-floured surface or parchment paper, cover them with a damp tea towel, and let them rise in a warm place for an hour until they double in size. Note: Don’t stack the slabs yet!

4. Preheat your oven to 400 F / 200 C / Gas Mark 6.

5. After the dough slabs have risen, place five of them gently onto the baking sheet(s) that you will use to bake the loaves. Place the other five slabs on top of the first five so that you end up with 5 two-tiered loaves in total. Make sure that you leave adequate space between each tiered loaf to allow for spreading during stamping and oven spring in the hot oven. The loaves are now ready to stamp!

6. The most common variety of Orthodox bread stamps that you can find for sale these days are contemporary wooden stamps like the Greek stamp pictured above. You can find many varieties of Orthodox bread stamps for sale online and you may also be able to find them at Greek, Ukrainian, Russian, Armenian, or other Orthodox Christian bakeries in your area.

7. To stamp the bread, this is the method that I found worked the best: Dust the tops of the loaves and the stamp itself with plenty of bran or semolina. This will ensure that the stamp does not stick to the dough when you pull it off. It will also ensure that the impression will be deep and will hold during baking. Press the stamp firmly onto the centre of the top slab and push down until you can see both of the slabs beginning to bulge out from under the perimeter of the stamp. Remove the stamp gently and repeat this step for all 4 remaining loaves.

8. Once the loaves have been stamped, they can be baked. Don’t be concerned about how flat the loaves are after stamping, they will biunce back beautifully once some hot air gets inside of them inside the oven. Bake the loaves for 45 mins until they are golden brown.

9. Once the loaves are baked, remove them and let them cool. At this point, you may want to marvel at them and covet them as I did. Or, perhaps you may want to learn how to section them correctly as a priest would during an Orthodox mass. If you find that you cannot see the stamp impression clearly on your loaves after baking, dusted a bit more flour on the loaf and rubbing it into the creases with your fingers or a brush will make the design of the stamp more prominent. You can, of course, eat the loaves as well.

Making Prosphora was a deep learning experience and one that I had put off for quite a long time. I am so happy that I finally gave it a try. I had always been curious about the form of this loaf and how the stamping process worked and stayed in the bread during the baking process. The flavour of the loaves was what you would expect: fresh, simple and pure. Perfect for an offering on any altar, really.

Following the baking of these loaves I had one last step that I observed that was critical to helping me discern if this Eucharistic loaf had any production or morphological connection to the Panis Quadratus loaves that were produced prior to the dawn of Christianity. This step was the most important one for me as the crust and crumb would surely reveal similarities if the loaves were made in the same fashion. In the past, I have heard bakers, theologians and archaeologists state that they theorized that the Roman ‘Panis Quadratus‘, or Kodratoi in Greek, was made by placing two slabs of dough together, similar to how Prosphora is made today. This is what I discovered when I studied my finished loaves and it does NOT support the assertion that ancient Graeco-Roman Panis Quadratus was made in the same manner as modern, or ethnographically recorded, Prosphora is made:

1.The Roman Panis Quadratus loaves excavated from Pompeii and Herculaneum, pictured above, do not show vertical pulling of gluten strands along the horizontal seam-line that result from the slabs rising in the oven during oven-spring and pulling at each-other in sections where the dough has adhered during the stamping process. These gluten-strands, as indicators of ‘pulling’ during upward rising during the bread’s baking process, are not present on the horizontal seam-line of the 2,000-year-old carbonized specimens of Panis Quadratus, which were produced in 79 AD. These strands are present, however, on the Prosphora, pictured above, which are produced by pressing two slabs together with a fair amount of pressure beneath the stamp. Another differentiating factor presented itself:

2. The 2000-year-old Roman Panis Quadratus loaves excavated from Pompeii and Herculaneum, pictured above, do not show a continuous horizontal seam-line running through the crumb. This continuous horizontal seam-line is present, however, in the crumb of the Prosphora, pictured above, and it is produced by pressing the two slabs together with a fair amount of pressure beneath the stamp. Interestingly, this seam does not disappear after baking and the unbaked dough does not transform into a homogeneous and unvarying crumb once baked. The two separate slabs are indeed visible and detectable after baking.

These two differences in crumb and crust features gave testing the popular two-slab manufacturing theory of Panis Quadratus a thrilling and definitive outcome. One that I want to test further by examining the carbonized bread data from the lab at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli that I gathered this past November. It should be noted that I also tested the two-slab theory this week using whole wheat flour for this recipe and the same defining features occurred. What I’ve concluded through this archaeologically-based food experiment is that Panis Quadratus was not made by stacking one slab of dough on top of another. Panis Quadratus was comprised of one solid portion of dough, not two.

Lastly, this experiment also leads me to consider that this form, as popular as it was from Greece and Rome to Byzantium… may have been made in many different ways as it migrated from one place to the next. Mothers teaching daughters, bakers teaching apprentices, slaves teaching slaves. Bread migrated with people and so did technique. Depending on the resources available, this popular form could have been made in many varying ways to achieve the same desired outcome: a round loaf with an impressed surface and a horizontal seam-line. To determine if Prosphora is definitively an evolutionary descendant of the Graeco-Roman Quadrati/Kodratoi will require more research and reading. It is exciting, however, to consider that this form of loaf is still present in a part of the world today that the Panis Quadratus was likely also produced in 2,000+ years ago. And it is doubly as exciting that the Panis Quadratus form could have been used to model a holy bread during the dawn of Christianity. It isn’t just archaeology or ethnography that can shine a light on this subject either; the presence of bread in early Christianity fills the historical written record to the brim from the New Testament to the letters of early saints.

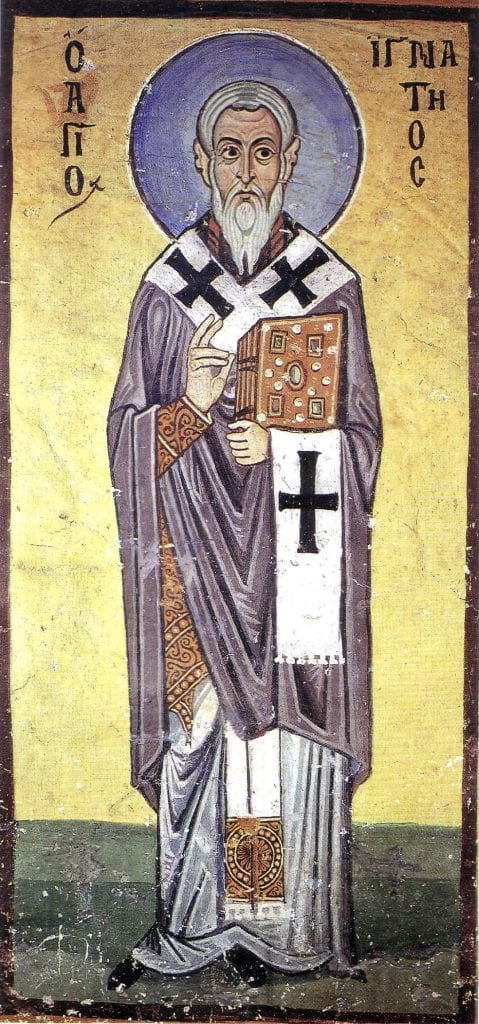

“I take no delight in corruptible food or in the dainties of this life. What I want is God’s bread, which is the flesh of Christ …”

– St. Ignatius, Letter to the Romans

Amen and pass the butter.

Thanks for a great article! I really enjoyed your research. I especially appreciate your devout, respectful tone. I’m a convert to Orthodoxy, a laywoman who makes Prosphora for our parish. I’ve attended Greek (US and Cyprus) & Antiochian (Arabic) parishes, and also made Prosophora with a Russian Parish. The one think I’d add to your amazing information is that every culture/geography/town/region has its own interpretation of the “right” way to make this bread. Some allow modern yeast, some do not. Some have two layers of dough, some do not. Some make it as a parish community, others make it in individual homes. I’ve ALWAYS seen it made only with refined flour – never with whole grain. I’ve never seen bran or semolina used on the outside of the loaf – and most Priests I know would not approve. But, I would not be surprised if it is done that way somewhere. It is good to remember that this bread is part of our community life as a culture (in addition to being part of a Sacrament that is Holy)- and just like everyone’s Grandma makes THE authoritative Chocolate Chip cookies – every community has a certain way to make the PERFECT Prosphoron. Thanks so much for a lovely article! I really enjoyed it : )

My Australian friend who is Greek shared this very fascinating article with me as we were discussing communion at her Greek Orthodox Church and at the Christian churches here in the United States. What I’m wondering is why did the Catholic and Protestant churches go with unleavened wafers instead of sticking to the Prosphora? The Prosphora looks like it was made with love locally, whereas the unleavened communion wafers are commercially made by machines in a factory.

Just stumbled upon this. What a beautiful article! Thank you!

Hi, I very much like your synthesis of history, archaeology, and culinary expertise. I started experimenting with this approach after reading Columella’s recipes on the use of Mediterranean herbs an ancient food preservation techniques. I started baking my own bread using a home-made started, and I just experimented with the panis quadratus recipe, which I really adore. However, being a Catholic theologian, I just wanted to add a further layer of meaning to a two-piece prosphora bread. The bread itself is full of meaning but adjoining the two pieces of dough into a single loaf symbolizes two inseparable natures in Christ, human and divine. As you already indicated, the seam doesn’t disappear once the bread is baked, and you cannot separate the loaves. Not that it adds anything special to the recipe, but that is a theological reason behind the technique. Cena bene!

Hi Entoni! That is really beautiful. Thank you for telling me this additional information! It makes the loaf all the more fascinating. – Farrell

Fab and fascinating article. I will deplore your blog some more, but felt I should add what little I know about the modern prosphoro.

I have baked prosphoro both with someone trained by Russian Orthodox bakers and with my own grandmother who was Cypriot. In The Russian tradition 5 small loaves are baked. These are made as you described but using the small side of the wooden stamp. In Cyprus (and Greece) this is not necessary. The larger side of the stamp has 5 sections so it’s fine to just make one large loaf. The large loaf was made, as suggested by Peggy Roll above, by shaping and stamping the dough then cutting a very deep score line along the edge. No bran or semolina were used, just strong plain flour. The dough is insanely stiff in comparison with typical modern dough. It was then baked in a low oven with a tray of boiling water on the lower shelf of the oven.

Obvious I will EXPLORE your blog. Apologies for the poor proofreading of autocorrect

🙂 No worries, we are all learning! – Farrell

Thank you for this info, Azimuth!! – Farrell

You should have a recurring role in Gastro Obscura! This is a great blog!

Thank you Rania!

A very interesting read! My only thought is about the flour and what grain is producing it. I think that this bread would have made with a grain relatively low in gluten and the bread would be much darker in colour.

This experiment needs to aim to replicate taste as well as appearance. What’s it like made with a heritage/ancient grain?

Over ‘n’ oot,

Dan

Hi Dan! What would lead you to believe it would have been made with grain with low/no gluten? At this point in history, many types of grains were used in bread making in Greece, Byzantium, Rome etc. Bolting the flour to achieve a refined and white colour and softer texture was also practiced for finer loaves or ritual loaves. Having surveyed some of the Pompeian loaves first hand I’ve seen the presence of gluten strands in the crumb and it’s very much there. The most common grains used to bake bread at this time were common bread wheat (T.Aestivum) and spelt. Modern ‘ancient’ grains aren’t truly ancient, per se, as they’ve changed some over time with selective cultivation etc. It’s best to consult archaeology to see what the bread actually looked like. Unfortunately… most of it is carbonised so no luck on the colour-front! 😉 – Farrell

I was very interested in this article. My understanding is that the edges of the round loaves were marked around the outside with a knife or blade of some sort which would produce the line without having two layers. I also remember reading that a string was used to encircle the loaf. It would bake into the loaf and then a loop would be used to hang the bread.