Good day, good coqui! Are you ready to drop everything that you’re doing right now to work on something that is far more important than taxes and way more delicious than that boring old salad you’re about to make? Because I know I am. Taxes be gone! The kitchen calls and so do the pages of De Re Coquinaria! Once in a while, a recipe like this one emerges from the archaeological and historical records and the gods themselves rejoice that it is once again being prepared for consumption… and that is exactly what happened when I first tasted this recipe. The clouds parted and a shower of grain spilled down from the heavens in through my kitchen window… It was that pleasing! So, if you’d like to win favour with gods and receive your own lifetime supply of grain, get your toga-sleeves rolled up and dust off your trusty mortar. But first… let’s explore some of the history the goes into this recipe:

Cheese-making in ancient Rome was a regular practice and many varieties of cheeses were prepared from fresh cheeses, similar to what we know as ricotta, to early forms of aged and brined cheeses. Columella tells us about cheese-making in De Re Rustica (Book VII, Chapter VIII) and tells us that: “It will be necessary too not to neglect the cheese-task of cheese-making, especially in distant parts of making the country, where it is not convenient to take milk to the market in pails. Further, if the cheese is made of a thin consistency, it must be sold as quickly as possible while it is still fresh and retains its moisture; if, however, it is of a rich and thick consistency, it bears being kept for a longer period. Cheese should be made of pure milk which is as fresh as possible, for if it is left to stand or mixed with water, it quickly turns sour. It should usually be curdled with rennet obtained from a lamb or a kid, though it can also be coagulated with the flower of the wild thistle or the seeds of the safflower, and equally well with the liquid which flows from a fig-tree if you make an incision in the bark while it is still green. The best cheese, however, is that which contains only a very small quantity of any drug. The least amount of rennet that a pail of milk requires weighs a silver denarius and there is no doubt that cheese which has been solidified by means of small shoots from a fig-tree has a very pleasant flavour.” We can see food frescoes at Pompeii that depict fresh cheese straining in wicker baskets. We can also find many references to Roman meals that incorporate cheese, especially in the writings of Columella and Apicius.

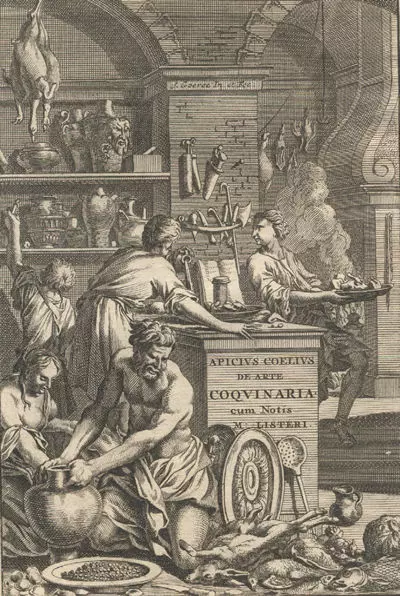

Who is Apicius? It is assumed that a man named Marcus Gavius Apicius was the creator or original compiler of the oldest surviving collection of recipes in Roman history: De Re Coquinaria (1st c. AD). The surviving written manuscripts of the Apician recipes date much later, however, as the collection that we study and refer to in the modern era was formally compiled and recorded in the Late Roman or Early Medieval period.

In the Roman documentary record, Apicius is referred to several times by writers such as Athenaeus and Seneca; he was said to have been an epicure who enjoyed the excesses of life and had food and dining standards that were almost impossible to meet. Pliny the Elder says the following about Apicius: “Apicius, the most gluttonous gorger of all spendthrifts, established the view that the flamingo’s tongue has a specially fine flavour” (Pliny, Naturalis Historia, X.133 – 77 AD); and “Apicius, that very deepest whirlpool of all our epicures, has informed us that the tongue of the phœnicopterus is of the most exquisite flavour” (Pliny, Naturalis Historia, X.68 – 77 AD). Marcus Gavius Apicius was clearly an intriguing figure, one whose tastes were respected, and one that many loved to write about in the ancient Roman written record. In the modern era, Crystal King took this several steps further by constructing an entire novel around fictional characterizations of Apicius, his family and staff, and a glimpse into what his life could have been like inside both his home and his social circles in her book, Feast of Sorrow. The Apician recipe collection have provided an invaluable secondary source of information to use alongside archaeological data when interpreting Roman food-related remains.

The Roman Sweet Tooth: Apicius’ Hypotrimma with Defrutum Glazed Spelt Biscuits

So, our man, Apicius, must’ve liked his mulsum a fair bit as he gives us nothing more than the ingredients with which to make hypotrimma. Fair enough, this was the order of the day, if and when recipes were actually transcribed in ancient Rome. We rarely get the weights or volumes when looking back on what was recorded. To make hypotrimma, Apicius informs us of the following ingredients:

“Pepper, lovage, dry mint, pine nuts, raisins, dates, sweet cheese, honey, vinegar, liquamen, oil, wine, defrutem or caroenum.”

Source: Apicius (De Re Coquinaria) by Christopher Grocock and Sally Grainger.

Grainger (2006) tells us the ‘hypotrimma’ means something ground up into a paste in a mortarium. At first glance, we will notice that this is something that the Romans seem to like to do a great deal: Put cheese and other edible ingredients into a mortar and smash it all together. We know this from making moretum. A mortarium, or a mortar, in a Roman kitchen is the same as our modern-day food processors that we use to dice herbs, nuts, or other ingredients, in order to make them easier to incorporate into a recipe with other ingredients. I used a mortar for this recipe in order to stay true to the original food processing technologies. For me it is important to experience the labour and the time expenditure that was necessary to make this in a Roman kitchen 2,000-years-ago. But you, my good Roman, can choose to use a knife and potato masher/mallet, or your modern Cuisinart mortarium (your electric food-processor) if you don’t have one of the stone or marble variety in your kitchen arsenal. Note: You can also make your own defrutum prior to making this recipe as well.

A nota bene before we proceed with preparation: About the spelt biscuits… Most of you who read this blog know that I am a staunch traditionalist when it comes to recreating Roman foods. I frown upon things like Roman ‘foam’ sauces or Roman ‘pinsa’ made of soy and rice flower… I am an experimental archaeologist who strives to interpret food-related archaeological data through experience, recreation and observation in order to get as close to the real dish as possible. But I also really like cookies and pretty things… and fancy cookie cutters. And, like moretum, this recipe required a ‘utensil’ to eat it with and Apicius was too drunk to provide us with a recipe for an edible utensil so what’s a girl to do? Moretum was eaten with flatbread, broken or cut, and used to scoop up the cheese thus making it easier to transport the food to the mouth. It also makes the meal more balanced and less rich when a starch is added in with the protein. The clam shell biscuit ‘utensils’ were made for this reason. They were also inspired by a rather long-standing debate in Roman bakery research so I like to think they’ll be acceptable under the ‘just for fun’ category, which is where my recipe for Cuneiform Gingerbread Tablets can be found… which attempts to argue that gingerbread and early writing systems emerged at roughly the same time… ?

During some recent research at Pompeii, a discussion arose around commonly used Pompeian commercial bakery nomenclature that has been published over the years and a common assumption that the bakeries that did not have mills must have made pastries. Some scholars call these bakeries: ‘Pastry Shops’. Hmm… Why? No artefact, image, or written reference about the bakeries of Pompeii have ever depicted bakeries without mills as being strictly relegated to making ‘pastries’ instead of bread. There is no evidence for remains of carbonized pastry in the archaeological record at mill-less bakeries at Pompeii either. This old label for bakeries without mills was often supported by a beautiful bronze clam-shell artefact that is in collections at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. It is often assumed to be a ‘pastry mould’ and is thus associated with the bakeries at Pompeii that do not have mills. In actual fact, evidence for these so-called ‘pastry moulds’ at Pompeii are derived from contexts that are domestic, not commercial and the most common typology of these moulds, the infamous bronze clam shell, is currently understood to be related to domestic bathing rites, not pastry-making. I state all of this as it is important information! I also state this as I will catch heck from my good friend, Cristina Hernandez, who is a domestic Roman bath expert and she will call me if she sees me making clam-shaped ‘Roman’ baked goods on my blog without qualifying that it is being done just for fun… and because they’re bloody adorable. So, with all of that said: Let’s dust off our clam shells and cook it old school! Here’s what you’re going to need:

Ingredients:

Hypotrimma

- 10 cracks / 1 tsp of pepper

- ½ tsp of Ajwain (Bishop’s weed), celery seed, or a handful of fresh lovage leaf

- 1 tsp of dried mint

- ½ cup / 65 gr of pine nuts

- ½ cup / 70 gr of raisins

- ½ cup / 70 gr of pitted dates (approx. 10)

- 3 cups of unsalted fresh or aged, soft mild cheese (eg. cow’s ricotta, sheep cheese, or goat cheese)

- 1 tbsp / 15 gr of honey

- 1 tbsp / 10 gr of red wine vinegar

- 1 tsp of garum/liquamen or Thai/Vietnamese fish sauce (Red Boat or Flor di Garum, for example)

- 1 tbsp / 15 gr of olive oil

- 1 tbsp / 15 gr of defrutum or grape molasses

Spelt Biscuits

- 4 cups / 650 gr of coarse-ground spelt flour

- 1 tsp / 10 gr of salt

- 1+1/2 cup / 425 gr of honey

- 1+1/2 cup / 425 gr of ricotta

- 2 tsp baking soda

- 1/2 tsp cinnamon

- 1/2 tsp cardamom

- 1 clam-shaped cookie cutter or any other decorative cutter of your liking

Here are the steps to prepare Apicius’ Hypotrimma with Defrutum Glazed Spelt Biscuits:

- Begin preparing the spelt biscuits as they’ll take a bit longer to prepare and bake and the hypotrimma will go much faster.

- Preheat your oven to 350 F / 175 C / Gas Mark 4

- Mix your biscuit dough by hand or in a mixer.

- Dust a large cutting board with flour. Roll the spelt biscuit dough out, using a rolling pin, to as thin as you can. You are trying to achieve something to the effect of a Roman digestive biscuit. We want it to be as thin as a ‘Digestive Biscuit‘ so it’s soft but also a bit crisp once they bake. If your pin sticks to the dough, flour the surface of the dough with more flour.

- Using your cutter, cut out as many biscuit shapes as you can and place them onto a baking sheet. Hint: If you cutter sticks to the dough and you can’t get the biscuit out of the cutter…. Use more flour on the dough surface!

- Once you cut all of the dough into the cutter shape, take a basting brush and brush the top of the biscuits with defrutum or grape molasses. If the cutter you’re using is a ridged cutter, like mine is, brush against the ridges as it creates more of a dramatic shadow effect that makes the biscuit rather beautiful.

- Bake these little beauties for 30 minutes. Time to make the hypotrimma!

- If you’re going to use a mortar, keep a large mixing bowl on the side to move processed ingredients into once they’re fully pulverized. If you’re using a food processor, dice up all of the ingredients together but the cheese to begin with. Add the cheese in last either as soft cheese, broken into bits, or smashed. If you’re using a mortar, pulverize each dry ingredient individually using your pestle and then transfer it into the large mixing bowl to be mixed together once all of the ingredients have been mulched. Add the cheese in last either as soft cheese, broken into bits, or smashed. Mix it evenly.

- Serve the hypotrimma in a serving bowl by piping it into the bowl (if it’s too wet) or by shaping it into a ball (use a bit of olive oil on your hands) if you’ve chosen to use a drier aged cheese and the mix is of a firmer consistency. Garnish the hypotrimma by sprinkling some dried mint on top.

- Once the biscuits are done, remove them from the oven and let them cool. You can place the biscuits around the hypotrimma in the serving bowl, or use them as a garnish on the hypotrimma and serve the surplus biscuits on the side. The choice is yours! There’s so much room for presentation creativity here, coqui! Let’s do Apicius proud!

And now, the best part of this exercise: Tasting the final result. To be honest, I was hesitant after I made this the first time as I am usually quite afraid of garum/liquamen when it’s incorporated into sweets and desserts, such as the Pear Patina that I made earlier this year. Heavily salted, pungent fish sauce going into a sweet cheese dish with dates and vinegar? What could go wrong??!!…… NOTHING. Absolutely nothing at all. The first sample of the hypotrimma was exquisite. Creamy, sweet, fruity, minty, fresh, airy…. with the most wonderful little pop of celery seed/ajwain in the mix that took it to a whole new flavour dimension that I have never experienced before. I was truly taken aback and completely impressed by the end result of this first attempt at hypotrimma. Granted, I chose the weights and volumes for the ingredients myself… but together, all of the ingredients combined, and the resulting flavours, indicated to me that Roman cooks and gourmands had a very profound understanding of how the ingredients they had available to them worked together to make dishes that produced very comforting, pleasant, and incredibly complex flavours. This is a recipe that I will make time and time again and I will be experimenting with it heavily in the months to come with respect to the cheese varieties going into the mix and with the ‘utensil’ accompaniments as well.

The glazed spelt biscuits were also a pure joy! The hint of cinnamon and cardamom in the biscuit went beautifully with the creamy, minty, hypotrimma. The texture was terrific and that is owed to the flatness of the biscuit but also the ricotta and honey giving it some chewiness. The defrutum glaze crowned the biscuit perfectly with an outer texture that was sweet and crispy, as baked glazes should be. While I was trying the biscuits, I kept repeating to myself: “By God girl, you’ve made the Roman Digestive biscuit! You should really try dipping them in milk like you did as a child!”… so I did. And it was just lovely. I like to think that the Romans would have done the same as well as most unleavened flat-breads or wheat-cakes had to be dipped into milk, wine, or water to soften them and make them palatable. Perhaps I can plead historic validity for my faux Roman biscuits on this premise alone?

Do report back if you give this recipe a try yourselves. You can join in the discussion on our Facebook page or leave a comment below on this page. And of you’d like to chat in person with me or about any of the other recipes, you can join me and many of the other readers and fellow coqui this summer in Tuscany for The Old School Kitchen culinary retreats! More information about this year’s events can now be found on the Events Calendar page as well.

Thank you for reading and keep cooking it old school!

I made both recipes, delicious! Enough to feed a Roman regiment though 😀 Served it to my kids since we’re studying Ancient History right now. I used a spade cookie cutter (think face cards) and the biscuits turned about looking like glazed ancient pottery jugs! So cute. Your articles are delightful.

Is grape molasses the same as grape must?

No. It is a suitable modern alternative (especially if you spice it) to the must reduction syrup-like condiment known as defrutum, in ancient Rome.

I found some Grape Molasses under the name Pekmezi at Amazon. The only ingredient listed was “concentrated grape juice”–it’s good stuff!

Question about the recipe for your spelt buscuits;from the ingredients, it looks like it was inspired by Cato’s Libum. Was that the inspiration for them?

Hi Drea, no it was not. There’s a fair bit more ingredients in them than Libum and they’re made of spelt as well. Thanks for giving them a go! – Farrell

test

Just a note about Defrutum. The Romans produced this by boiling grape juice down in lead pots. Archaeologists reconstructing this process tested the result and found it contained enough lead for one tablespoon to cause chronic lead poisoning. They liked lead because it acted as preservative and had a sweet taste.

Your recipe is fascinating and highlights the fact the Romans were gourmets.

Yes, you are correct! You’ll see a whole section related to lead acetate in the Defrutum recipe… which, incidentally, advises not to use a lead pot. https://tavolamediterranea.com/2018/05/17/mediterranean-triad-grapes-grains-olives-defrutum/

I’m going to be making my first batch of fig rennet cheese pretty soon, as the sap is just starting to run. I’m going to try this recipe using that! I don’t have access to defrutum. Do you think it would work with pomegranate molasses?

Hi MaryAnne! Pomegranate molasses is a perfectly acceptable substitution. Romans grew and consumed them regularly. Grape molasses is also an option. If you need the biscuit press for this recipe, you can get it at our shop now as well! –> https://tavolamediterranea.com/shop/

Thanks!