Quest’articolo è pubblicato anche in Italiano qui: https://tavolamediterranea.com/2021/04/17/bread-for-the-gods-pharmakos-barley-cakes-with-cheese-and-figs-italiano/

Good day, good reader! How are you doing today in your part of the world? I don’t know about you, but I’ve had enough of this COVID-19 pandemic already. Be gone, pestilence, be gone!

Today in the United States we hit a grim milestone of 4 million recorded cases of COVID-19. The United States is now the COVID capital of planet Earth and, while being told to stay at home for extended periods of time without making contact with other humans seems like an easy feat, there’s only so much news-watching and curve-spiking that a girl can take before she throws down the remote control and takes matters into her own hands. Most of you know by now that when the going gets tough, I turn to my ancestors for guidance to see how they survived historically challenging situations. Because history teaches us everything, if we preserve it and refer to it for past lessons, both good and bad. Well, the going certainly is tough for many of us right now, and, as a nation, we’re not really doing justice to science, to our ancestral knowledge, or to the lessons that the gods have taught us in the past. Clearly the gods are pissed as heck right now and the mask-shaming half-measures we have taken thus far to eradicate COVID-19 in the USA have not pleased them, whatsoever. So rather than cry in my pultes, I am electing that we up our game and take this matter to the powers that be ourselves. That’s right, folks! It’s time to take this situation into our own hands and what better way to do this than with some old-time religion… some old-time ANCIENT GREEK and ROMAN religion:

It’s time for a SACRIFICE!

You read that right, good reader. We are going to make a sacrifice, just as our foremothers and forefathers did, for millenia before us, when life got tough and they got scared. But before you call PETA on me, let’s take a moment to look at this practice in ancient Greek and Roman ritual culture:

To sacrifice something in ancient Greece or Rome was to offer up something of value to the gods to show gratitude, or to request assistance or favour. The gods controlled everything, from grain and wine to the sea and the sky. Sacrificial offerings could be anything from cattle and birds, to fruit, eggs, or ‘cakes’ (breads) made of grain and cheese, such as libum.

Not everyone in ancient Greece or Rome could acquire an animal with ease, nevermind sacrifice a perfectly useful one to the gods, so non-living alternatives were often offered instead, such as: bread made in the form of animals or objects; terracotta votive replicas formed into shapes of food; or even flour pressed into wafers, such as Mola Salsa, which was offered to Fornax, the goddess of ovens. The concept of bread or flour wafers being used as a ritual food item that is a non-living offering and a method of purification may sound familiar to some of us who are Catholic: The Holy Eucharist. The Communion wafer (Western Church) and the Prosphoron (Eastern Church) symbolize the body and nature of Christ who ‘sacrificed’ himself for everyone else’s sins and impurities so that his followers would not have to make a living offering and end a life themselves. For Catholics — who are a part of one of the key historical contributions of the Roman Empire to the modern world — the communion wafer represents the blood and body of Jesus Christ through transubstantiation.

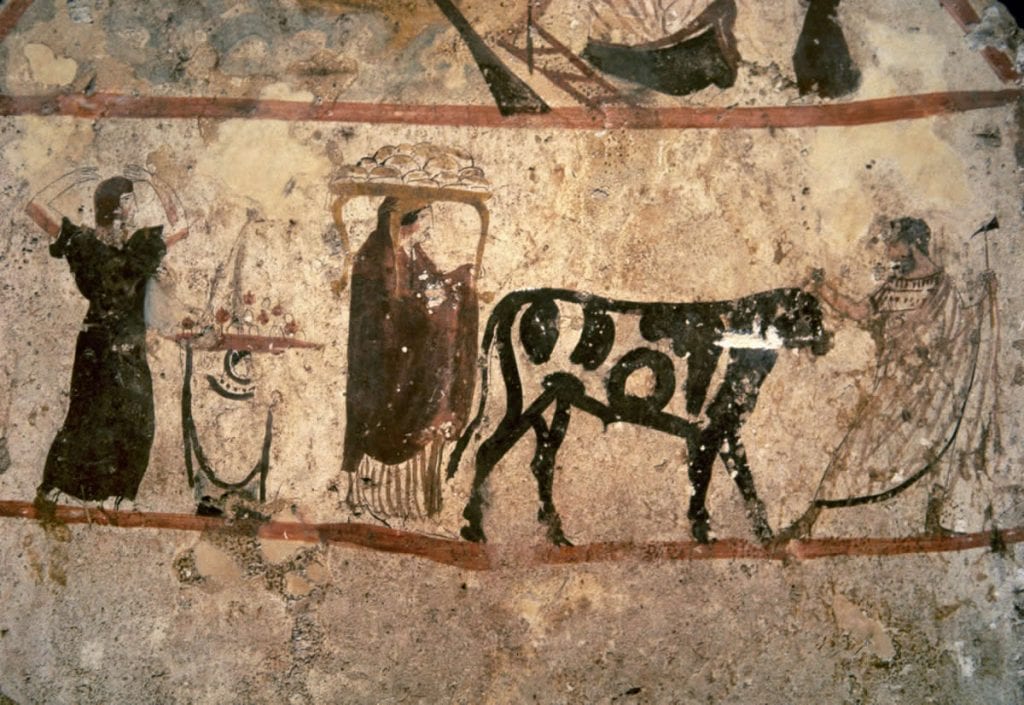

Roman lararia frescoes are also detailed sources of ritual evidence with respect to sacrificial offering practices and the foodstuffs that were offered in lieu of animals. From this evidence, we can learn how the ritual was conducted, who it was conducted for, and what items were valued and placed on the altar. In Roman ritual offerings, eggs were a popular choice, which tells us that not only were they valued enough to be given to the gods, but they were easily obtained as well.

In the lararium fresco above, which is from a bakery in Pompeii, we see an altar before a woman (Vesta, the goddess of the hearth) who is seated between two lares. The altar is flanked by two serpents (each a guardian spirit, or genius loci) and would typically have an egg or two, perhaps a pine cone, or fruit, sitting atop it. The foods would then be burnt and offered to the gods via the smoke. The purpose of this offering was to ensure that the household space was protected by the household gods, the lares and penates, and that the family was protected by the genius, the spirit of the head of the house.

So when a pestilence rolled into town, which it did quite regularly back in ancient Greece and Rome, you’d better believe they were fully prepared with a rite and something of value to sacrifice to the gods to preserve their health and the health of their communities. And this is where the Pharmakos comes in.

A Pharmakos, in ancient Greece, was a human sacrificial scapegoat. Generally a man who was ugly, criminally inclined, or offensive to those around him. The pharmakos, or pharmakoi (pl.), would be the offering, the actual sacrifice meant to appease the gods and prevent the pestilence from taking hold. It is debated, however, as to whether the pharmakoi were metaphorically ‘sacrificed’ by simply being run out of town, or if they were actually flogged, stoned, set alight, and killed. Diogenes Laertius (3rd c. AD) writes of Cretan philosopher, Epimenides, controlling pestilence with a pharmakoi sacrifice in the 6th c. BC:

“Hence, when the Athenians were attacked by pestilence, and the Pythian priestess bade them purify the city, they sent a ship commanded by Nicias, son of Niceratus, to Crete to ask the help of Epimenides. And he came in the 46th Olympiad (596-593 BC), purified their city, and stopped the pestilence in the following way: He took sheep, some black and others white, and brought them to the Areopagus; and there he let them go whither they pleased, instructing those who followed them to mark the spot where each sheep lay down and offer a sacrifice to the local divinity. And thus, it is said, the plague was stayed. Hence even to this day altars may be found in different parts of Attica with no name inscribed upon them, which are memorials of this atonement. According to some writers he declared the plague to have been caused by the pollution which Cylon brought on the city and showed them how to remove it. In consequence two young men, Cratinus and Ctesibius, were put to death and the city was delivered from the scourge.“

Alas, poor Cratinus and Ctesibius. I wonder how they met their deaths? Greek poet and satirist, Hipponax, sheds a bit more light on the subject in the 5th c. BC:

“The pharmakos was an ancient form of purification as follows. If a disaster, such as famine or pestilence or some other blight, struck a city because of divine wrath, they led the ugliest man of all as if to a sacrifice in order to purify and cure the city’s ills. They set the victim in an appropriate place, put cheese, barley cake and dried figs in his hand, flogged him seven times on his penis with squills, wild fig branches, and other wild plants, and finally burned him on wood from wild trees and scattered his ashes into the sea and winds in order to purify the city of its ills.”

Hipponax, Fragments, XIV (Tzetzes, Chiliads)

God’s great trousers! That’s a tall order, isn’t it? Unfortunately, my squill flogging days are behind me, so that’s out. And we’re not allowed outdoor fires in Malibu, so that’s out. And we are also not able to take the ugliest man in our land and fill his hands with cheese, barley cake, and dried figs,… and run him out of town for good… thus purifying our lands of all its ills. So, I think we should focus all of our ritual energy on the other ‘offering’ mentioned in Hipponax’s passage above: the barley cakes with dried figs and cheese! If they’re meant to be offered to the gods along with the Pharmakos, perhaps we’ll offer our barley cakes to our household genius instead? It can’t hurt to try, can it? Here’s what you’re going to need:

Pharmakos Barley Cakes with Cheese and Figs

Ingredients

Barley Cakes

The recipe that we will use for the barley cakes is derived from a reference to maza, and ancient Greek barley cake, from the Seven Books of Paulus Aegineta:

“The maza, as Zeunius explains it, consisted of the flour of

The Seven Books of Paulus Aegineta (7th c. AD)

toasted barley pounded with some liquor, such as water, oil,

milk, oxycrate, oxymel, or honied water.“

- 325 g (2-3/4 cups) barley flour

- 120 g or ml (1/2 cup) water

- 15 g (1 tbsp) olive oil

- 15 g (1 tbsp) white wine

- 30 g (2 tbsp) whole milk

- 30 g oxymel (2 tbsp) honey and vinegar combined

- optional: 5 g (1 tsp) baking soda

Topping

- Dried figs

- Defrutum/sapa or grape molasses

- Fresh, pressed, unsalted cheese or ricotta

- Honey (just in case)

- Poppy seeds (for fun)

Implements

- Cutting board

- Baking sheet

- Rolling pin

- Bench scraper

- Biscuit or ravioli cutter

- Parchment paper

- A whisk

Preparing the Barley Cake Dough

- Combine all of the liquids together and whisk it thoroughly.

- If you’re opting to add the baking soda (which will give the barley cake lighter texture), stir it into the barley flour so it is evenly distributed. Note: There was indeed bicarbonate of soda in the Classical Mediterranean.

- Combine the liquid and the flour and gently fold it together by hand until a firm ball of dough is formed. If your dough is too wet or too dry, feel free to add a bit more flour or water. You want a firm ball of dough that will handle nicely when it’s time to press it.

- Cover the dough with a damp tea towel and let it rest for 2 hours.

- Note: At no point are we going to knead the barley dough. It’s pointless to do so. There’s is very little gluten structure in this dough so it will tear and come apart easily. Be gentle with it.

Baking the Barley Cakes

- Preheat your oven to 400 F / 200 C / Gas Mark 6.

- Take a large cutting board and dust it liberally with flour.

- Place the ball of dough onto the centre of the cutting board.

- Dust your rolling pin and gently roll out the dough until it’s approximately 1/2 cm thick. If you have used baking soda, you’ll notice that the dough is quite fluffy. Roll it out gently, don’t apply too much weight.

- Using your biscuit or ravioli cutter, gently cut out your barley cakes and place them on your baking sheet on a sheet of parchment paper.

- Depending on the size of your cutter and the thickness of your dough, you’ll get anywhere from 12 to 16 barley cakes.

- Once the biscuits have been placed on the parchment paper/baking sheet, place the cakes into the oven to bake for 20 – 30 minutes. Again, this will depend on the thickness of your cakes. Check them at the 20 minute mark and if they’re still too pale… keep baking until they’re golden!

- Remove the cakes and let them cool before dressing them.

Dressing the Barley Cakes

- Dress each cake first on a work surface before plating it for presentation.

- Drizzle defrutum/sapa or grape molasses over the cake face in any pattern that suits your tastes.

- Drop a dollop of defrutum/sapa or grape molasses on the centre of the cake. This is what you will seat the figs and cheese on. If your defrutum or molasses is too runny, use thick honey in a pinch as it won’t run.

- Place a thinly sliced, small wedge of cheese on the centre of the cake and book-end it with a figs on either side. Alternatively, you can place a fig in the centre of the cake and lean a thinly sliced wedge of cheese against it.

- Optional: Sprinkle with poppy seeds for additional garnish and flavour.

Right, back to the gods. The primary purpose of these barley cakes is to offer a few of them to our household genius. Alright, alright… I know what you’re thinking: “But I am the genius in my household!” I know, I know. I am the genius in my household too… No one deserves MENSA candidacy or a guest spot on Jeopardy more than you and I, but that’s not the kind of genius I am talking about today. I am talking about the genius that is the spirit and divine nature of your house: The soul of your family; the spirit of your ancestors; the power of the love inside your home.

So with your household genius in mind, take one of your barley cakes and place it somewhere in your home where the ‘heart’ is, either in your kitchen or sitting room, or even in the vestibule or main foyer of your house, which is where you sometimes find lararia in Roman homes. Do it as often as you like. When you place the barley cake where it will sit as an offering to your genius, say the words: “Be gone, pestilence, be gone!”… and then walk away. Now you can go ahead and eat one or four of them yourself because they’re rather tasty, in my opinion. They actually remind me of a Graeco-Roman Fig Newton. Chewy, figgy, crunchy goodness… with a bit of creamy cheese.

Now, you can rest easy with the knowledge that, in addition to wearing your mask and keeping a safe distance from others, you made one more small sacrifice in your commitment to fight COVID-19 today, one that is founded in love and is backed by some pretty serious spiritual and historical potency! It is this spirit and love that will protect you and your family and the health inside of your home from the pestilence in our communities right now. It is this spirit that will ultimately drive off COVID-19 as it reminds you daily to listen to sound scientific and medical advice, to remember that we’re all in this together, and to be patient and have faith. We’ll get there. It’s just going to take a few small sacrifices along the way.

If you enjoyed this post, join the conversation on our Facebook, Twitter and Instagram pages! Or consider joining us this summer for The Old School Kitchen: Summer Camp: A stay-at-home series of archaeo-culinary master classes hosted on Zoom by Farrell Monaco. Classes for adults and kids! Register here

Thank you for existing. That is all.

I try. 😉 Thank you for the kind words, Carlos! – Farrell

I’m in love with this! So much fun to read. Thanks!!

Thank you Nancy! – Farrell

There are some big issues of ritual and etymology here. First off, what was the role of squills in this penis-flogging malarkey? All I know about squills or scillas, is that they’re a pretty blue-flowered bulb of the lily family, and have been used medicinally for millennia, for example for heart complaints, but need to be used with care as, like digitalis, they are poisonous if used inappropriately or in excess. None of which seems particularly relevant to this ritual.

Then, the Greek word pharmakos for the human scapegoat. Even if that isn’t etymologically related to the Greek word pharmakon (‘drug/poison/spell’), it’s hard to see how the Greeks themselves could have avoided associating them. Should we read this as ‘medicine’ against the pestilence or misfortune threatening the community? Or a ‘spell’ to avert it? Or both?

And I know it doesn’t necessarily follow that similar-sounding-words for similar things in different languages are cognate, I have to wonder about maza and matzoh. Any thoughts?

Hi Victoria. You’d have to ask Hipponax the question: Why squills? Indeed, I think the metaphoric ‘sacrifice’ by running a sick or crooked person out of town could perhaps be viewed as a ‘remedy’ in a ritual sense. This is assuming they didn’t actually kill the pharmakos. Maza/Matzoh… indeed. I have thought the same thing on many occasion! – Farrell

This is such a cool idea! I love the connection to our ancient ancestors.

Since making defrutum isn’t likely in my future (due to the sad lack of vineyards in Manitoba–that’s my story and I’m sticking to it!), would balsamic glaze be an appropriate substitute? Also, what about pomegranate molasses, or are we wanting to stay with grapes?

Hi Linda! I would use pomegranate molasses or honey as a substitute. – Farrell