I don’t know about you but I spend a great deal of time thinking about food. Who doesn’t, really? Food is a central part of my life. I enjoy cooking it, reading about it, writing about it, and photographing it. I eat large meals several times a day, it is a pleasurable experience for me, and this is how I sustain myself to keep going from one day to the next. But do I value it in the same way that my fore-mothers and fore-fathers did? Am I connected to food in the same way that my ancestors were? One of the best ways to explore this question is through the archaeology of food.

I don’t know about you but I spend a great deal of time thinking about food. Who doesn’t, really? Food is a central part of my life. I enjoy cooking it, reading about it, writing about it, and photographing it. I eat large meals several times a day, it is a pleasurable experience for me, and this is how I sustain myself to keep going from one day to the next. But do I value it in the same way that my fore-mothers and fore-fathers did? Am I connected to food in the same way that my ancestors were? One of the best ways to explore this question is through the archaeology of food.

The archaeology of a food is a fascinating area of study but one that is also multi-layered. If we are to simplify it, we could study animal bones and plant remains in the archaeological record and conclude that human beings in the past ate seafood, red meat, lentils, or barley, for example. Beyond the basic remains of food, however, we can detect what resources were available locally, what foods were plentiful; and what foods were ‘special’ or rare if they are represented in lower concentrations. But there’s so much more to the archaeology of food that just diet, resources and the remains of food itself and we can confirm this by examining some of our own modern food cultural practices: Christmas dinner isn’t just about eating turkey with cranberry sauce; a vegan breakfast burrito isn’t just a low-fat alternative to bacon and eggs; and dinner on a first date isn’t just about picking any old restaurant out of the phone book — there are many more factors involved when it comes to the role that food plays in our daily lives. Food is more than sustenance; it is a reflection of who we are. It is a reflection of our cultures, associations, familial groups, political and religious beliefs, and traditions. It is a reflection of identity and one of the best places to study this phenomenon in a modern context is on Facebook.

Not a day goes by on Facebook that we don’t see one of our friends post a “lunchie” on their timeline for all to see and marvel at. This is the term that I use to describe the ubiquitous “lunch selfie” that we see almost daily on most social media platforms: The sexy lunch shot of a glistening salad crowned with rainbow radish and pea shoots; the carefully staged overhead shot of a bowl of Ph? with chopsticks positioned just so; or the low-lit shot of an edible gold-dusted chocolate ganache. You know the type of photo I am referring to. The photo that is alluding to much more than just the food pictured in the frame. This “lunchie” is telling you who your friend is, what preferences they have, how they view themselves, how they want to be viewed by others, what foods they find to be attractive, and what foods and food experiences they value. In addition to this, your friend may also be telling you what they abhor, disapprove of, or are intolerant to based on what is not present in their photo such as meat, bread, alcohol, or fast-food, for example. These images are projections of identity on the part of your friend and food is just the vehicle for that projection. But what does any of this have to do with food archaeology? This food culture that we observe and participate in daily on Facebook actually didn’t start the day that Facebook went live in 2004. These types of personal and cultural expressions through food have been present in the archaeological record for millennia. All one has to do is visit the ancient site of Pompeii (Italy) to see similar expressions of identity through food but in an ancient context.

Not a day goes by on Facebook that we don’t see one of our friends post a “lunchie” on their timeline for all to see and marvel at. This is the term that I use to describe the ubiquitous “lunch selfie” that we see almost daily on most social media platforms: The sexy lunch shot of a glistening salad crowned with rainbow radish and pea shoots; the carefully staged overhead shot of a bowl of Ph? with chopsticks positioned just so; or the low-lit shot of an edible gold-dusted chocolate ganache. You know the type of photo I am referring to. The photo that is alluding to much more than just the food pictured in the frame. This “lunchie” is telling you who your friend is, what preferences they have, how they view themselves, how they want to be viewed by others, what foods they find to be attractive, and what foods and food experiences they value. In addition to this, your friend may also be telling you what they abhor, disapprove of, or are intolerant to based on what is not present in their photo such as meat, bread, alcohol, or fast-food, for example. These images are projections of identity on the part of your friend and food is just the vehicle for that projection. But what does any of this have to do with food archaeology? This food culture that we observe and participate in daily on Facebook actually didn’t start the day that Facebook went live in 2004. These types of personal and cultural expressions through food have been present in the archaeological record for millennia. All one has to do is visit the ancient site of Pompeii (Italy) to see similar expressions of identity through food but in an ancient context.

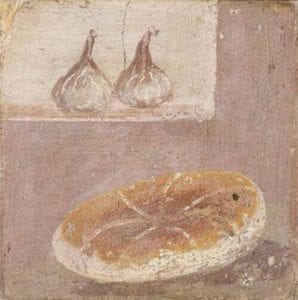

On the second floor of the MANN (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli) in central Naples (Italy) is a small room that holds most of the food-related frescoes that were removed from the walls of several houses at Pompeii during the various phases of excavations. Almost every inch of space on the walls of this room is adorned with still-life paintings that depict what may have been commonly found in Pompeiian pantries and gives the viewer an idea as to what ingredients were typical in the Pompeiian diet. But beyond the face-value of these images, these frescoes tell us what foods Pompeiians preferred to eat, what foods they aspired to eat, what foods they had access to, and what foods they found beauty in.

These stunning pictorial representations of foodstuffs at Pompeii not only give archaeologists an idea as to how the Pompeiian people expressed identity through the foods that they ate, or desired to eat, but they also provide supporting evidence with which to fill in the blanks when the archaeological record cannot produce a ‘complete picture’ of what the Pompeian diet looked like using carbonized grains and olive pits alone, for example.

The panis quadratus, the iconic 8-sectioned rounded loaf of bread, is also featured in several frescoes at Pompeii as were they represented highly in the archaeological record at the site. 81 carbonized panis quadratus loaves were excavated from the Bakery of Modestus. What we may interpret from these representations is that the bread was produced in high volume at Pompeii but that it was also valued enough by Pompeiians to be painted on to the walls of several of the homes and businesses at Pompeii. This type of Roman bread was often considered a ‘luxury’ bread as the flour was refined several times producing a lighter, leavened loaf. The representation of this loaf in Pompeiian food frescoes could have symbolized status, industry, a well-fed community or household, or a community with unfettered access to grain and a complement of competent bakers. These images weren’t just about the bread alone. These are projections of identity depicting status, preference and access to resources through food imagery and these “lunchies” are almost 2,000 years old, dating to the first century AD.

While I stood in front of the Pompeiian food frescoes for the very first time in the summer of 2013, I couldn’t help but to compare the two media of expression and see the stark similarities. The curiosity that I felt in studying the food frescoes at the MANN made me wonder what archaeologists of the future would interpret about us, the humans of the digital era, when they find our modern projections of self through the digital food images that we post on our virtual walls on a daily basis. Archaeologists of the future will excavate zettabytes of digital culture, not material, sifting through billions of photos looking for clues about who we were and what we valued. If our food images are going to say anything about us it’s that food was indeed valuable to us and that we were as connected to it as all the generations who came before us were but that our medium of conveying this value and connection was simply different. In the digital era, we have continued to connect with our food, value it, protect it, fight for it, and we have continued to use it as a mode of expressing identity as human beings. We are what we eat and the archaeology of food will continue to allow us to explore food and identity in the human past while shining a light on our own relationships with food at the same time.