Salvete Omnes! It’s time to tie the donkey to the quern-stone and roll up our toga sleeves once again… we have some ancient cooking to do! In the weeks to come, we’re going to be looking at some key areas of Roman food resources and this recipe is just the beginning. The next few articles will be exploring The Mediterranean Triad; the three most valued agricultural resources during Classical Antiquity: Grapes, Grains and Olives.

‘The Mediterranean Triad’ is a term used to describe the three most prominent crops in the Classical Mediterranean diet: Grapes, Grains and Olives. These crops were central to the Roman diet in that they were versatile and commonly used components of Roman food preparation, cooking and medicine. Grapes were consumed as fruit, wine and sauces; grains were consumed as breads, cakes, porridges and digestive aids; and olives were conserved and consumed as fruit or used for many other daily purposes in the form of oil.

We can see the Mediterranean Triad and its central nature to the Roman diet as it is represented frequently in the Roman archaeological record: Archaeobotanical evidence such as olive pits, grape seeds and whole grains; technological evidence such as quern-stones (grain mills), olive and grape presses, and ovens or hearths; and pictorial evidence such as frescoes or reliefs. Another key archaeological element that demonstrates how much grape, grain and olive products were being transported throughout the Empire are ceramic transport amphorae.

Amphorae sherds, often dubbed ‘the archaeological garbage of the Mediterranean’, can be found in abundance in archaeological contexts throughout areas that were once Roman territories. These vessels were in use as food transport containers for a period of approximately 1,000 years. The word ‘amphora’ is derived from the Greek word ‘amphoreus’ or ‘amphiphoreus’ and is described as a two-handled ceramic vessel that is meant to contain foodstuffs. The Greeks adopted the utilitarian shipping vessel design from the Phoenicians and Egyptians and began manufacturing their own versions of transport amphorae from the 7th century BC forward. From there we see amphorae begin to reach the Greek colonies in southern Italy from the 4th century BC onwards. We begin to see transport amphorae disappear from the archaeological record in Late Antiquity.

What makes amphorae an invaluable source of food-trade data in Roman archaeological studies is that they provide us with insight into volume and product origin. It would be impossible for archaeologists to discern how many olive products, for example, were transported into the city of Rome from provincial producers if we could only rely on long decomposed organic evidence. But when we have millions of ancient ceramic transport amphorae sherds, scattered throughout the former Roman territories, we have a much broader picture of the volume of foodstuffs that were being imported and consumed by Romans during the Republican and Imperial periods.

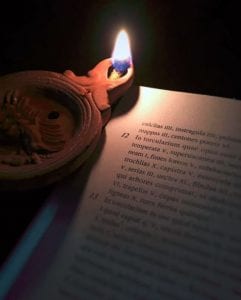

This article is the first in the Mediterranean Triad series and it will briefly explore olives and their presence in the Roman diet. Olives were first cultivated 7,000 years ago in the eastern Mediterranean and Levantine region. Evidence of this cultivation has been found in the archaeological and early documentary records in the Levant (modern-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and Iraq). Olives were one of the first commercial products to be grown and traded in the eastern Mediterranean during the Bronze Age. Greek and Roman farmers valued the olive so much that they attributed its origin to the Gods. Columella called the olive tree the ‘queen of all trees’ and this assertion was supported by the many uses that olives had in Greek and Roman daily life. Olives were consumed as fruit, but only after conserving them in brine or vinegar, but it was the oil that this fruit produced that was the most useful to the Roman people. Olive oil was used in food preparation, cooking, and conservation. One of the earliest Roman cookbooks, ‘Apicius‘, records over 30 recipes that incorporate olive oil. The Romans used olive oil for medicinal purposes as well when treating cuts and burns, hemorrhoids, and other skin afflictions. Olive oil was also used as a cleansing agent when bathing and an annointing liquid during rituals or special occasions. In addition to these many uses, olive oil was also used as fuel in oil lamps to create light so that the Roman people could work and walk about long after dark.

One of the best places to start exploring the archaeology of olives or olive products in the Classical Mediterranean is Monte Testaccio in Rome. The archaeological site, which is located in Testaccio in Rome (Italy), is a 2,000-year-old man-made hill that is comprised entirely of broken olive oil amphorae. This ‘ceramic landfill’ is a testament to the staggering amount of olive oil that was brought into the city of Rome from the 1st to the 3rd centuries AD. The hill itself is approximately 36 metres in height with a perimeter of 1,490 metres and presents an overall volume comprised of 580,000 m3 of ceramic amphorae sherds. The amphorae collection at Monte Testaccio is the largest remnant of a once bustling olive oil distribution system depicting imports from Hispania Baetica to Rome through the annonae urbis and militaris; the food doles for the Roman people and its military. The hill still stands to this day and has been an active archaeological site, under the auspices of the Comune di Roma and CEIPAC (University of Barcelona) for over 30 years. It is possible to see portions of the hill and its structural make up when walking through Testaccio en route to the New Testaccio Market or the Protestant Cemetery.

If we want to explore some literary representations of the olive during Classical Antiquity, it is always best to turn to the documentary record. Cato the Elder provides us with several recipes on how to prepare and conserve olives in his Republican-era farming manual ‘De Agricultura’ (circa 160 BC). One of the most interesting recipes that he presents is for a Roman ‘tapenade’ of sorts that combines olives with fennel and a variety of herbs and spices forming a dish that sounded absolutely enticing when I first read about it. Cato’s ‘tapenade’ is called ‘Epityrum’ and I’ll be making this simple but flavourful recipe for this article. But we can’t just make Epityrum on its own, now can we? No…. because we’re going to need something to scoop it up with! So we’ll be making a simple Roman unleavened flatbread from the same era in combination with the Epityrum. We will then see the olive mixed with the grain in an edible pas-de-deux of Roman cookery from the Mediterranean Triad. So if you’re ready to taste a bit of history, roll up your sleeves and dust off your mortars and pestles. Here’s what you’re going to need:

The Mediterranean Triad – Grapes, Grains and Olives: Epityrum and Flatbread

INGREDIENTS

Epityrum

- 1 kg of black or green (or mixed) pitted olives

- 3 tbsp of olive oil

- 3 tbsp wine vinegar

- ½ tsp dried mint

- ½ tsp of coriander powder

- ¼ tsp of cumin

- 1 diced bulb of fennel

- A few leaves of edible rue or a handful of cicoria (dandelion greens)

Flatbread

- 2 cups of whole wheat or emmer flour

- ¾ cup of tepid water

PREPARATION

Let’s begin by preparing the flatbread first as it will require a bit more time.

Flatbread

Begin by preparing the flatbread first. It is going to take a while for the dough to firm up as it rests and the gluten begins to bind the dough. This flatbread recipe was taken from a previous recipe on Tavola that originated from a Vergil poem and I feel that it’s suitable for this recipe in many ways: Not only does it come from roughly the same time period but the bread makes itself very useful as an eating utensil, or a scoop, for dishes such as moretum or epityrum.

- Mix the dough for the flatbread by hand or by using a mixer. If you’re like me and you enjoy the back-breaking labour of milling your own flour, you can find instructions on how to do this in the original recipe. If you are not milling your own flour you can throw your back out by simply lifting the bag of flour from the pantry shelf and retrieving 2 cups of flour from it and placing it in a mixing bowl.

- Begin adding the water and kneading/mixing the dough. I began by adding 1+3/4 cups of flour to 3/4 cup of tepid water in a mixing bowl. I mixed my dough by hand in the bowl and then transferred it onto a cutting board for the kneading process. I reserved ¼ cup of my flour for dusting the dough during the kneading process. If you find that your dough is too wet or tacky go ahead and add in the remaining ¼ cup of flour.

- Let the dough rest for an hour on a cutting board. Cover it with a tea towel to make sure that the dough does not dry out. You can begin preparing the epityrum now and return to the next section (4.) when the flatbread dough has rested for an hour.

- Preheat your oven to 350F/175C/Gas Mark 4.

- Now that the dough has rested, flatten it out on the cutting board and give it a few ‘stretch and folds’. You can do this by dusting the top of the dough and the surrounding edges, flattening the dough with your hands, and folding the sides, one over the other, a few times. You’ll notice that the dough is starting to firm up and become more elastic. Cover the dough again and let it rest for 30 minutes.

- After the dough has sat for 30 minutes and your oven has reached baking temperature, it is time to bake the flatbread. Roll the dough out onto a dusted counter top or cutting board and section the dough into 8 sections. Take each section and roll it into a ball in your hand and then flatten it into a round disk. Use a rolling pin or your palm and fingers to do this. Dust the dough, bottom and top, with additional flour if the dough sticks to the work surface.

- Bake each flatbread for no more than 15 minutes. As they bake, you’ll begin to see them balloon like a pita bread. Once they’re golden brown and fully inflated, you can remove them from the oven to cool.

Epityrum

Here we will follow Cato’s instructions on how to make the Epityrum. In his agricultural writings titled ‘De Agricultura’, Cato tells us the following:

‘Epityrum album nigrum variumque sic facito. Ex oleis albis nigris variisque nuculeos eicito. Sic condito. Concidito ipsas, addito oleum, acetum, coriandrum, cuminum, feniculum, rutam, mentam. In orculam condito, oleum supra siet. Ita utito.’

From this we can understand the following (in English):

‘Recipe for a confection of green, ripe, and mottled olives. Remove the stones from green, ripe, and mottled olives, and season as follows: chop the flesh, and add oil, vinegar, coriander, cummin, fennel, rue, and mint. Cover with oil in an earthen dish, and serve’

(Cato, On Agriculture – CXIX. Source: Loeb Classical Library)

Here is how I prepared my epityrum. I began by dicing all of my pitted olives and the fennel bulb on a cutting board. In a mortar, I used the pestle to mulch my herbs and spices together into a paste. (Note: I used a few dandelion greens instead of rue to add the bitter component that rue would have contributed to the original recipe. While rue is still available in some parts of the world, it is rare and not commonly used in modern cooking.) I then added my herbs and spices together in a mixing bowl with the diced olives and fennel, vinegar, olive oil and folded all of the ingredients together gently. Cato tells us to put the epityrum in a preserving jar, covered in oil. I took one small liberty by making the mixture a bit more easy to present and serve immediately: I added the 3 tablespoons of olive oil into the mixture and then packed the epityrum firmly into a bowl. I then turned the bowl over onto a serving dish and let it stand for a few minutes until it slowly let go of the sides of the bowl. With a few taps on the top of the bowl, I was able to lift the bowl and the epityrum held a dome-like form on the serving plate. I then drizzled it with the same peppery, punchy olive oil that I used in the recipe.

At this point you can also garnish the epityrum with some diced parsley and surround it with olives on the serving dish. Serve the epityrum with the flatbread. When it’s time to sit down and dig in to your epityrum you’re going to notice that the flatbread will serve you very well! You are truly eating like a Roman in this instance by using this bread as an eating utensil that can either sop up or scoop up a gustatio or promulsis. Romans did not use forks when dining and they often used their hands or bread to eat what was served during their daily meals. This particular flatbread is durable and forms a natural inner cavity during the baking process, just like pita bread, that can easily be filled with food when it is time to dine.

Cato’s ‘Epityrum’ recipe produced a bold, tangy and fresh tasting appetizer that marries so many different Mediterranean flavour components beautifully. A tart olive base combined with fresh fennel, bold cumin, and floral coriander and mint made this recipe something that tastes almost synonymous with summer. It’s very fresh, clean and tangy and filling as well. Similar to moretum, this recipe is also another example of a simply prepared Roman meal that actually presents complex ancient Mediterranean flavours while placing you directly into an immersive, historical dining experience. Not only are you tasting the flavour profiles that ancient Romans enjoyed but you’re using a common ancient Roman dining technique in the process as well. Adding Vergil’s flatbread recipe to Cato’s epityrum is a perfect combination of complementary recipes featuring two products in the Mediterranean Triad: Olives and Grains. They go so beautifully together that it’s easy to understand why we still marry these two ingredients together today while cooking in the modern era.

Cena bene and good eating to you!

Feel free to leave comments or suggestions about this article using the comment form below. Did you try this recipe? If so, feel free to join the discussion and post photos on Tavola’s Facebook page.

Happy to have stumbled on your blog while googling “Mediterranean Triad”. Well done!

Thank you for popping by! Keep cooking it old school! 🙂 – Farrell

Ah I’m so happy to have found your blog. I found some rue at a farmer’s market this weekend & I have since been on an internet odyssey to find recipes. I found several mentions of Epitryum online but yours is the most in-depth & I love all the background information about amphorae.

Also love your dome presentation. Presumably the purpose of covering it in olive oil was to preserve it longer term?

Jess

Thanks Jess! We just made epityrum today with a large group at our cooking retreat in Rome. It’s one of my favourite dishes. I think the oil was meant to flavour it and hold it all together a bit better. The fennel really makes that dish! Thank you for reading. 🙂 – Farrell