That’s right, folks. It’s time to get the git out.

Recently, I have been delving deeper into the archaeological and documentary records, looking for evidence of the many weird and wonderful ingredients that are incorporated into Roman breads, as this is an integral (and achievable) aspect in exploring the sensory interpretations of Roman breads. Taste and texture are determined by the ingredients and food technologies that were used in the Roman Mediterranean. We often see the words ‘spelt’ and ‘farro’ being used when referencing Roman bread ingredients but this is only a fraction of the big picture. There was so much more involved in Roman bread-making than just the flour that held the loaf together, so many variables, which is why I have decided to write a series of posts about the many varieties of Roman breads and the key ingredients found within them… so stick around for that! But first… let’s get to the git!

Git?… What the heck is git? That was the exact same question I asked myself recently when I stumbled across a passage in Historia Naturalis referencing “Git” and its relationship to commercial Roman bakeries. I read the passage, giggled like a four-year-old telling a poop-joke, and then I sat in silence for an hour as it overturned so many assumptions I had previously made about the ingredients used in commercial Roman breads. Pliny the Elder writes:

“Git is grown for use in bakeries…“

Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis, Book XIX (1st c. AD)

Oh. My. God.

So… you mean there was more than just grain and water in the commercial bakeries of Pompeii and Ostia Antica? And pistores were using more than just flour, starter, water and (maybe) salt in commercial breads? Praise be! But what is this ‘git’ business anyways? Well, if you’re from the United Kingdom, you’ll probably be well familiar with this word at your house. “Git” is something that your friends or family call you when you’ve done something stupid, said something rude, or you’ve behaved like a complete pillock. And if your formative years were spent watching “Monty Python’s Flying Circus“, as was the case at my house, you’d associate the word “git” with useless, poorly behaved bell-ends who make arses of themselves in public, as portrayed in the infamous Python sketch “Mr. and Mrs. Git“. To the Romans, however, who had no exposure to Monty Python and who had not seen “The Life of Brian” yet, “git” was a wild plant seed that was used in cooking and baking.

Git, or Roman Coriander, is known scientifically as Nigella sativa. It is commonly found in Southern Europe, North Africa and Southwest Asia and is also referred to as black caraway, black seed, black cumin, fennel flower, nigella, nutmeg flower, Roman coriander, and kalonji. The seeds are harvested from the pistils of the flower and were used for spices and medicines in the Classical Mediterranean.

Archaeobotanical evidence of git has not been found in commercial bakery settings at Pompeii, as far as the excavation reports show, but evidence of coriander seeds (Coriandrum sativum L.) have been found at Herculaneum and perhaps this spice was used in breads as well as in aromatic beverages and medicines, as Columella tells us (De Agricultura, XII, 8.1; VI, 33.2). Varro also discusses how to use the word ‘git’ (and probably snickered as much as we did) in his writing on the Latin language:

“Git ‘fennel’: Varro in the eleventh book of the treatise addressed to Cicero states that this form ought to be used in all the cases; but people quite commonly say gitti in the ablative.“

Varro, On the Latin Language, Book XII, Fr. 22

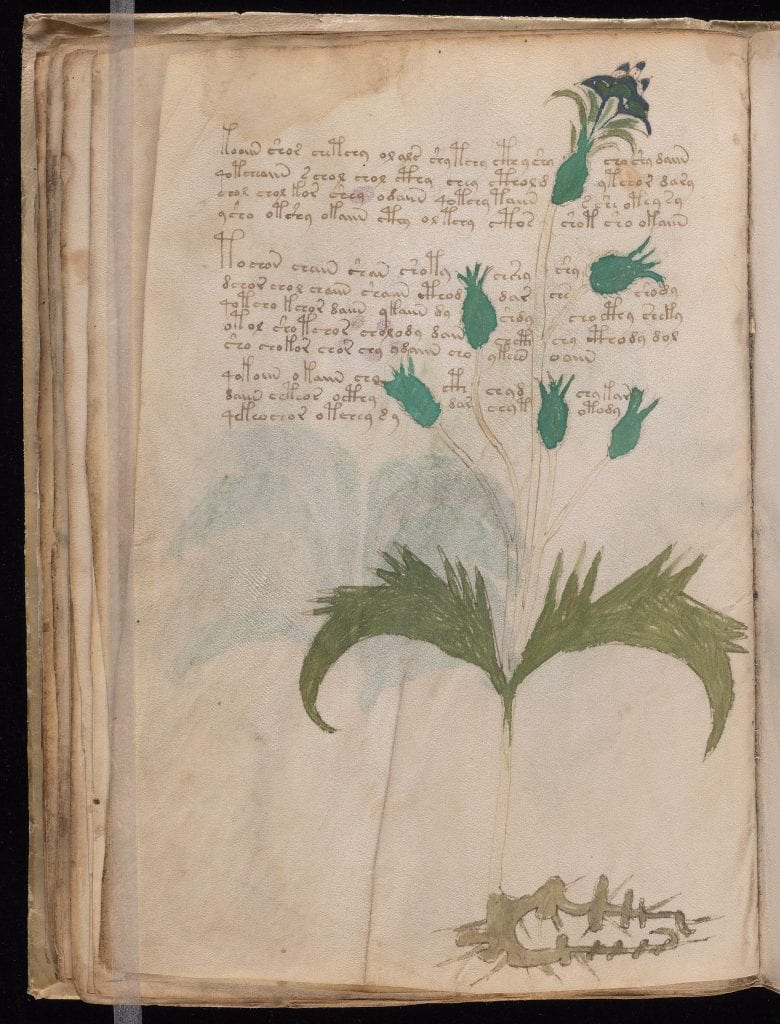

In addition to these ancient written references above, git is also depicted in the Voynich Manuscript, a botanical guide that was hand-written and -painted in the 15th century AD, pictured below.

To go about making a bread recipe with git, I started by using coarse flour milled from naked bread wheat. That’s standard triticum aestivum; this was the wheat that was found in situ in one of the mills at The Bakery of Modestus (Pompeii) in 1862 by Giuseppe Fiorelli and his team. I also used refined (bolted) flour to make the bread crumb lighter as was the practice for some of the ‘finer’ loaves made in Roman commercial bakeries. In addition to the Roman coriander (git), I am only incorporating bread starter, water, and salt in this recipe. The salt being purely speculative, of course… as we all know how expensive salt was during Classical Antiquity! If you have trouble sourcing git (as it’s not readily available at the corner shops anymore…) you can try to use coriander seed instead and then try again the recipe again with Nigella sativa when you can find some online or at your local Middle Eastern, North African or Indian cook shops.

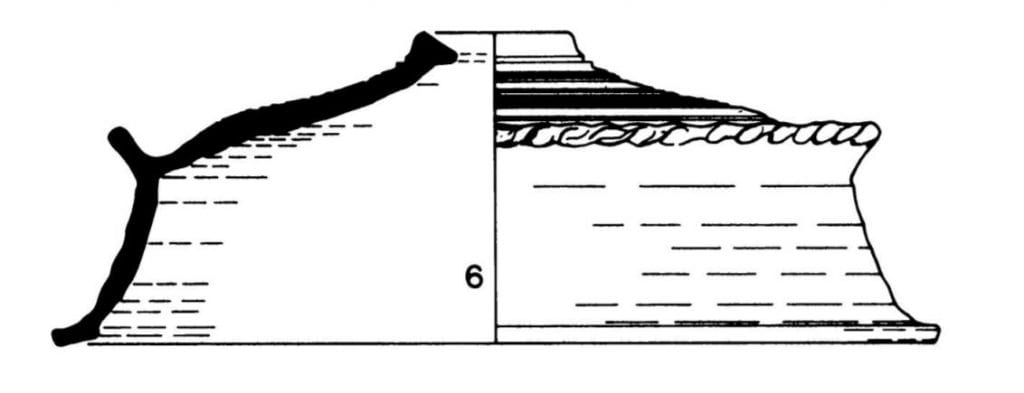

This recipe is being made using a Clibanus (or a Testum) that I recently ordered from Graham Taylor at Potted History. These baking vessels (which were often comprised as just a cover, or a cover and a base) were typically used in the Republican Roman period in domestic settings prior to the commercial boom that occurred following the Third Macedonian War in 168 BC. Why does this period of use matter? Well, following the Third Macedonian War is when we see a large commercial boom and an increase in urbanization take place in Rome and on the Italian Peninsula. Country-dwellers begin to move into towns and cities, to seek work and opportunity, and commercial bakeries begin to emerge in the urban landscape to supply the urban poor, who did not always have cooking facilities in their small insulae, with their daily bread. With the emergence of the Roman commercial bakery came the industrial high-volume beehive ovens which are the primary food technologies used to define commercial bakery spaces in Roman archaeological settings. The beehive oven is, effectively, a large clibanus; it is also a smaller cousin to the fornax, the large ovens originally used to parch and dry grain. Like the fornax or the beehive bread ovens of Pompeii, the clibanus is a closed, domed, ceramic baking environment that retains heat and moisture and bakes the bread as efficiently as possible with no heat loss. With beehive ovens becoming prominent in the late Republic, the clibanus continued to be used but wasn’t used as often as it was during the Republic and as urban dwelling became more common.

The Clibanus, with the bread dough inside, would have ideally been placed into the embers of a wood-burning hearth, cooking platform, brazier, fire-pit or on a tripod above a fire. Putting a clibanus inside of an oven would be effective as well but it isn’t efficient in small volumes as you are essentially placing a small ‘oven environment’ inside of a large ‘oven environment’. Therefore, clibani and testa are best used for small batches, and personal or domestic use which explains why there is no evidence of clibani found in Roman commercial bakeries. A modern-day ceramic cloche is similar to a clibanus and can be used in a fire-pit or in a modern oven environment as well.

Baking with the Romans – The Key Ingredients: Git

Ingredients (Yields 2 small boules):

- 2 cups / 325 gr of white/refined bread wheat flour

- 2 cups / 325 gr of whole bread wheat flour

- 1 cup / 250 gr of bread starter (leaven)

- 2 cups / 500 ml of tepid tap water

- 2 tsp / 10 gr of salt

- 1 tbsp / 10 gr crushed git (Roman coriander) seed or coriander seed

- Semolina flour for dusting/handling

Preparation:

Preparing the dough:

- Begin by feeding your starter the night before bread-making. Nourish it with flour and water and leave it out overnight on the counter, to activate it and get it ready for a day’s work! If you do not have a starter, you can make your own by following this recipe: Pliny the Elder’s Leaven Recipe.

- On baking day, prepare your bread dough in the morning as this loaf will likely have a 6 to 8 hour turn-around depending on the heat and humidity in your part of the world.

- In a large mixing bowl, dissolve the bread starter in the two cups of water and whisk it together.

- Grind the git or coriander seed using a mortar and pestle.

- Add the salt and ground git (Roman coriander) in with the flour and stir it together for a few seconds.

- Add the flour, salt and crushed git, bit by bit, into the liquid and gently fold it all together, kneading the wet and dry ingredients into a mass.

- Once you have a well kneaded, cohesive ball of dough, cover the mixing bowl with a damp tea-towel and let the dough rest and rise for a few hours. You should end up with approximately 1.3 kg of dough.

- After a few hours of rest, cut the dough into two even sections and fold and roll the dough into a boule; a small round loaf. Use semolina flour for your hands and for your work surface so you can handle the dough without it sticking to anything.

- Cover the boules with a damp tea towel and let them rise until they double in size.

Baking the loaves:

- You can make this bread in several ways: Ideally you want to do this in a wood-burning oven, hearth, brazier, on a tripod above a fire, or in a fire-pit. You can also do this in your conventional oven if you do not have access to outdoor fire-cooking facilities. You can use a baking sheet but a cloche or clibanus will give you a texture and a spring to the loaf that cannot be achieved otherwise!

- Preheat your oven to 450 F / 230 C / Gas Mark 8.

- Place your cloche or clibanus/testum in the oven and preheat it empty for 1 hour.

- ‘Score’ your loaves in any fashion that you like. I chose to score mine using a reed and I created 4 wedges as there are a few specimens of panis quadrati cut into 4 wedges that were excavated at Pompeii.

- After an hour of preheating, remove the clibanus or cloche from the oven (with oven mitts!) and then, using a bench scraper or spatula, slide one loaf gently into the centre of the clibanus base. Place the cover back on and put it back in the oven.

- Turn your oven down to 400 F / 200 C / Gas Mark 6 and bake the loaf for 30 minutes, then remove the top and bake it again for another 15 minutes to brown the top of the loaf.

- Once golden-brown, remove the loaf and let it stand until it’s cool. Serve it plain or with olive oil or fresh cheese.

The results of this baking experiment using a recreated clibanus were quite telling and quite satisfying! First off all, it goes without saying that when you preheat a ceramic oven environment to a piping hot temperature and then you bake bread in this tighter, closed environment…. the quality of the crumb and the crust is markedly different. The moisture from the bread dough is trapped inside the clibanus so it allows for more oven spring when the loaf begins to expand beneath the dome during baking. Not only this, but the moisture also gives the crust that chewy, rip-it-apart-with-your-canines texture that so many bakers aim to achieve with humidity ovens and spray-bottles of water. There’s no need for this when the dough itself creates steam inside of the tight baking environment of the clibanus.

Further to this is the incredible crumb that results from, again, the hot, steamy environment inside of the clibanus. The moisture from the bread dough is trapped inside the clibanus so it allows for more oven spring when the loaf begins to expand beneath the dome during baking. The resulting crumb will make you want to run out today and get a job as an apprentice pistore. Holes! Everywhere! And it took little to no work and did not require 39 successive half-hour stretch-and-fold sessions either.

The texture and the taste were the two sensory front-runners in this experiment. I can now imagine how the textures would have differed between baking domestic breads in a clibanus and baking commercial breads in the large beehive ovens. The domestic loaves baked under a clibanus or testum would have been chewier and softer while the commercial loaves baked in the larger ovens would have been firmer and drier.

The taste of the loaf itself, with the fragrant Roman coriander coming through periodically, is so comforting. The odd floral, herbal-tasting burst of the Roman coriander pops its head up once in a while but does not overtake the simple, wholesome flavour of the loaf and the sweet, nuttiness of the wheat. The salt balanced it all nicely as well! I am now reminded of a comment that was made in an article published in the Guardian last weekend that I was interviewed for. A food historian inferred that it was difficult to apply a modern sense of taste to interpret ancient senses of taste and flavour profiles in experimental food recreations. I don’t agree with this! While the quality of Roman coriander, or the quantities may have varied… the combinations of all of those flavours together present something unique and telling about the Roman palate and about the specific ingredients that influenced their taste-buds and shaped their food culture and their meal-planning. For example: making fresh cheese with fig-rennet, a Roman practice, leaves a slightly bitter under-taste in the cheese. This is a by-product of Roman cheese-making that results in an indelible change in taste that is as detectable now as it was 2,000 years ago… and it is a regular flavour Romans would have been accustomed to that we are not familiar with in the modern era. Yet it tells us that some fresh Roman cheese would have tasted bitter! There’s no debating this and modern experimental recreation led to experiencing that stark flavour contrast between our palates and theirs. This git bread follows this same pattern: the flavour is so unusual and so foreign to my palate that it tells me something about Roman bread-making, bread flavour preferences, and the additives that they used, even if it doesn’t suit my flavor preferences or please my modern palate in any way. Because taste isn’t always about direct personal pleasure; it’s about the ingredients themselves and the people who worked towards achieving those unique tastes. And clearly the Romans enjoyed certain herbs and spices in their breads, especially if Pliny felt it necessary to document that git was being grown for use in the commercial bakeries! Oh. My. God. This is big news for bread in the Classical Roman world! The Romans got their git out!

Happy baking and keep cooking it old-school.

Note: If you have food-allergies and any of the ingredients found in this recipe are new to you, please consult your allergist first before trying new food-stuffs that you have not tried before! Safety first!

Join in the discussion on our Facebook page or leave a comment about this recipe below on this page. If you’d like to chat in person with me or about any of the other recipes, you can join me at one of the The Old-School Kitchen live events taking place at a museum or venue near you. More information about this year’s events can now be found on the Events Calendar page.

really amazing!!! you have to write a book, I can’t wait to have it :9

This is a great recipe! I thought beforehand that the git might be the kind of taste you like once in a while but could easily tire of if you had it too often. But no: I’m happy to eat this bread at every meal, and so are my husband and father (in lockdown I haven’t had many people to share it with, but everyone I have given some to loves it).

I’ve made it three times and I reckon I’ve now got a handle on it. I do find that it needs less water than given in the recipe; the first time I made it, the mixture was more like cake mix than dough, and couldn’t be kneaded in any meaningful sense at all. That may partly have been because I hadn’t been able to get strong bread flour and was using ordinary plain flour, and the ‘soft wholemeal spelt’ which was the only wholemeal I could get really was soft, no kidding. (Here in the UK getting hold of flour was really, difficult for months: we learned that of all the flour mills in the country, only two were set up for packing it for retail. The MD of one mill was quoted as saying ‘I can sell you a ton of flour, no problem. Sell you a kilo? No chance.’) But even with the right flour I still find it doesn’t need that much water.

I haven’t got a clibanus but I do have a traditional slip-glazed clay bakestone from Pururuela in Spain, and a metal casserole upturned over it keeps in the moisture, though of course it doesn’t hold heat as a ceramic lid would do.

I’ve been using untreated rock salt that I brought back as a souvenir from Salzburg a while back; I just grind it up as I need it. I remember at the Panis Quadratus Zoom tutorial that you said sea salt was the correct thing, but the Hallstatt salt mines were active right through the history of the province of Noricum, so surely any Roman baking bread there would have used the local salt. Living as I do in the southeastern corner of Britannia, with a view of the town of Durobrivae from my upper windows, which is just a few miles downstream from where Vespasian crossed the river in 43 AD to fight Caratacus and Togodubnus, I think a lot about how Roman cooks would have made do with local ingredients. E.g. I hadn’t any cicoria or rue to put in Columella’s moretum, but I do grow Good King Henry, which is a kind of goosefoot, tasting rather like bitter spinach, and used that instead. Not the same, but a rough equivalent in flavour, I think.

Just a couple of queries about making the git bread:

– In your steps 6-7 it’s not really clear how much kneading is desirable. Just enough to mix it? Twenty pulls? Less? More?

– While the first loaf is baking, what’s the best way to keep the second? Back in the warm place? Or cool in the fridge?

This bread is great! So good that I have made it twice in one week! The crust was incredible (I used an enamel oven proof pot with a lid since I didn’t have a clibanus)!

Thank you greatly for this article and recipe! I have a quick question: Where might I buy a clibanus?

You’re welcome! From my good friends Sarah and Graham at http://www.pottedhistory.co.uk/

Tell them Farrell sent you. 🙂

This looks amazing!