* Since publication of this post, my research into the form, flour, and tools of the trade in relation to the Panis Quadratus bread remains of Pompeii has been updated significantly and is available to read in The Bloomsbury Handbook of Experimental Approaches to Roman Archaeology. *

Friends, Romans, Baking Enthusiasts: Lend me your ears! …. Who wants to make Pompeiian Bread? If you do then you’ve come to the right place.

Many of us have seen the iconic images of carbonised loaves of bread that were excavated from Pompeii, Herculaneum, and other settlements in the Bay of Naples (Italy), that were destroyed during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. But have you ever wondered what that bread might have tasted like? How was it made? What ingredients went into those loaves? What is that funny-looking, sectioned bread called anyways? It’s called ‘Panis Quadratus‘, my friends, and historically it is one of the most beautiful representations of food ever found in the archaeological record.

Named because of the four linear ‘cuts’ made to the loaf, creating eight evenly distributed sections that were cut into the loaf prior to baking, ‘Panis Quadratus’ was represented a great deal in the archaeological record at Pompeii both in art and in artefact. The reconstructed recipe for Panis Quadratus below provides an opportunity to explore the history of Pompeii and Roman food culture further by using a very appropriate sensory avenue: taste. We’ll also familiarise ourselves with the baking labour process by getting our hands dirty, using some good old-fashioned elbow-grease, and making this loaf from scratch from start to finish as we add our own creative touches. If you read the first part of this two-part series on Roman bread-baking (Baking Bread with the Romans: Part I – Pliny the Elder’s Leaven) then you may have already made your own leaven (also known as bread starter, yeast, sourdough starter, pasta madre, levain) which is called for in this recipe. If you have not been able to make your own leaven yet, you can return to the first article and give it a try or you can buy your own. It’s often possible to find starter for sale at your local bakery or grocery store. But before we roll up our sleeves and tie the donkey to the quern-stone, let’s have a bit of history first, shall we?

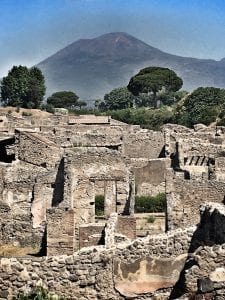

Pompeii

The history and destruction of the ancient city of Pompeii is a topic that has captured the hearts and minds of historians and archaeologists for hundreds of years. There is a tragic and romantic aspect to the manner in which the city and its population met its demise, during a catastrophic volcanic eruption in 79 AD, which creates a strong desire for many to learn more about the site and the people that inhabited it. Mount Vesuvius took thousands of lives on that fateful day in 79 AD and buried several settlements, not just Pompeii, in ash, pumice and pyroclastic flow. The result was a horrific event that essentially created an invaluable archaeological time-capsule along the eastern Bay of Naples preserving many impressions of Roman daily life for many future generations to study. Pompeii alone hosted a population of approximately 12,000 people on a grid covering almost 66 hectares of land; it is now widely accepted to be the most important archaeological site in the world.

Now, if you are like me, you probably enjoy reading about Pompeii or studying the endless sources of Classical historical data that the site has to offer. If you’re just starting out on this voyage of discovery, you’re in for a beautiful ride. But if you’ve already put your toe in that water you’ll have also realised that ‘studying Pompeii’ is something that you will be doing for the remainder of your life. There is no end of research, discovery, theory and interpretation that can come from studying Pompeii, or Herculaneum, for that matter. There is also no end to the avenues of study that you can choose from once you dig a bit deeper into the material culture that the ancient ruins have to offer: architecture, art, civic infrastructure, engineering, construction, epigraphy, ceramics, metallurgy, trade, sociology, theology, politics, and foodways. Each one of these avenues of Pompeiian history tells us a great deal about daily provincial life in the Roman Republican and early Imperial periods.

The area that I enjoy researching the most at Pompeii, of course, is food. Food-related archaeological data conveys a great deal of information about people and their daily lives; it can also tell us a lot about other objects or contexts in an archaeological setting. Food can provide insight if radiocarbon dating is used, for example, to date organic food residue, or we can use food remnants themselves as a relative dating tool to contextualise other objects found in the same environment. For example, closer examinations of food remnants related to the Vesuvian eruption recently resulted in a challenge of the eruption date of August 24, 79 AD. Some archaeologists now believe that the eruption occurred later than the currently accepted date. Here’s why: Preserved fruit and nuts that were examined further were known to have been ripe in the autumn and wine-making processes in ceramic dolia were found to have already been underway by the time that the eruption had occurred. All of this new food-related data thus connoted a harvest, or autumnal time-frame for the eruption, over that of a late summer date. This debate is still ongoing but it is fascinating to see how food-related archaeological data from Pompeii and the surrounding areas can contribute to understanding the bigger picture in so many ways.

What fascinates me the most about Pompeii and the daily lives of its residents was its love of bread. In fact, if you gave me a huge research grant and a lifetime supply of water and sun-screen, you’ll likely find me camped out, alongside Enzo the stray dog, in one of Pompeii’s thirty-five bakeries. Why? Because bread was the backbone of Pompeii’s daily diet; the bread bakers were powerful people in Roman society; and the bakeries themselves are incredibly telling and sensory environments. You see, bread was a critical commodity at Pompeii. It required massive quantities of grain, fire-wood, and slave and animal labour to produce a daily supply to feed 12,000 people. Donkeys walked in circles tirelessly, for hours on end, rotating the quern-stones (grain-mills) that ground the wheat; slaves did the same when animal-labour was not possible. The ovens were fired around the clock and enough grain had to be imported from within the region or from provincially confiscated territories to supply the Roman people with their daily bread. Bread was prepared daily, in high volume, often in the home but mostly in commercial bakeries run by a Corpus Pistorum (or Collegium Pistorum): a veritable trade-union of powerful bakers who were likely looked upon as a Roman version of the ‘Hoffa teamsters’ of the day. The men who controlled the bread and the commercial ovens often ran for office or influenced civic elections themselves. A common saying of the day was to say that a baker ‘gave good bread’, ‘bonum panem fert’, which meant that he could be a trusted community member or a potential civic official.

To understand the power that bakers once held in Imperial Rome, all one has to do is stand in the shadow of the enormous tomb of master baker Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces that was erected outside of Porta Maggiore in Rome during the 1st century BC. Professional bakers in Rome, and in Pompeii, did not exist until the 2nd century BC and it is theorised that this advancement in specialised crafts has everything to do with the conquering of Macedonia for the Republic by Aemilius Paulus. It is also assumed that Pliny the Elder’s reference to Greek knowledge of leaven indicates that yeast likely became a component of Roman bread-making during this time as Greek bakers were employed in Roman settings: “The Greeks have established a rule that for a modius of meal eight ounces of leaven is enough.” (Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis – Book XVIII-26(11)). This also suggests that the advent of leavened bread-making by the Romans in the 2nd century, despite the feelings of disgust or impurity that ‘putrefied and rotten dough’ invoked in many, brought bread to a whole new level of social and dietary significance.

In order to explore the loaves of bread themselves and look into the ingredients that were used in Roman breads, we can refer back to other references in the documentary record from Pliny the Elder. In the following passages he references grains that were used to make bread:

Spelt: “Of all these grains barley is the lightest, its weight rarely exceeding fifteen pounds to the modius, while that of the bean is twenty-two. Spelt is much heavier than barley, and wheat heavier than spelt.” (Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis –Book XXVI-11);

Wheat and Leaven: “Of the various kinds of wheat which are imported at the present day into Rome, the lightest in weight are those which come from Gaul and Chersonnesus; for, upon weighing them, it will be found that they do not yield more than twenty pounds to the modius. The grain of Sardinia weighs half a pound more, and that of Alexandria one-third of a pound more than that of Sardinia; the Sicilian wheat is the same in weight as the Alexandrian. The Bœotian wheat, again, weighs a whole pound more than these last, and that of Africa a pound and three quarters. In Italy beyond the Padus, the spelt, to my knowledge, weighs twenty-five pounds to the modius, and, in the vicinity of Clusium, six-and-twenty. We find it a rule, universally established by Nature, that in every kind of commissariat bread that is made, the bread exceeds the weight of the grain by one-third; and in the same way it is generally considered that that is the best kind of wheat, which, in kneading, will absorb one congius of water. There are some kinds of wheat which give, when used by themselves, an additional weight equal to this; the Balearic wheat, for instance, which to a modius of grain yields thirty-five pounds weight of bread. Others, again, will only give this additional weight by being mixed with other kinds, the Cyprian wheat and the Alexandrian, for example; which, if used by themselves, will yield no more than twenty pounds to the modius. The wheat of Cyprus is swarthy, and produces a dark bread; for which reason it is generally mixed with the white wheat of Alexandria; the mixture yielding twenty-five pounds of bread to the modius of grain. The wheat of Thebais, in Egypt, æhen made into bread, yields twenty-six pounds to the modius. To knead the meal with sea-water, as is mostly done in the maritime districts, for the purpose of saving the salt, is extremely pernicious; there is nothing, in fact, that will more readily predispose the human body to disease. In Gaul and Spain, where they make a drink by steeping corn in the way that has been already described—they employ the foam which thickens upon the surface as a leaven: hence it is that the bread in those countries is lighter than that made else- where.” (Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis –Book XXVI-12);

Salt in Bread Dough: “At the present day, however, the leaven is prepared from the meal that is used for making the bread. For this purpose, some of the meal is kneaded before adding the salt, and is then boiled to the consistency of porridge, and left till it begins to turn sour. In most cases, however, they do not warm it at all, but only make use of a little of the dough that has been kept from the day before.” (Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis – Book XVIII-26(11)).

(From: Pliny the Elder, Natural History. Perseus at tufts.edu)

Now, if we refer to this information above and couple it with the visual information that has been gleaned from frescoes and carbonised bread that was excavated from Pompeii, and other sites that were decimated by the eruption of 79 AD, we have a fairly accurate idea of what should go into a recipe for Panis Quadratus. Of course, we’ll never be 100% sure of how this loaf was made or why it’s shaped the way that it is (what the heck made that centre groove anyways??)…but speculation, interpretation and experimentation is half of the fun and it’s also an important part of education. So with that said, let us roll up our sleeves, tie the donkey to the grain-mill and make some Panis Quadratus! Note: If you’re like me and you don’t have a donkey on hand to mill your flour, pre-ground flour will suffice! Here is what you’re going to need:

Baking Bread with the Romans: Part II – Panis Quadratus

Note: this recipe is inspired by the research of the author and is developed for a non-academic, lay readership. It does not reflect the ingredient quantities or ratios proposed by the author in her academic publications.

Ingredients

- 3.5 cups (600 gr) of Spelt Flour

- 3.5 cups (600 gr) of Whole Wheat Flour

- 3 cups (700 gr) tepid water

- 1 cup (200 gr) of leaven (starter)

- 2 tsp salt

- Coarse ground flour or wheat bran for dusting

Implements

- Cooking twine

- A sharp knife or bread lame

Preparation

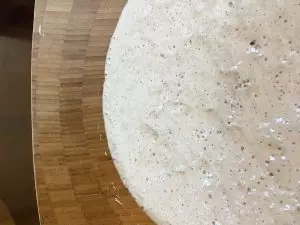

Note: Before you start this recipe, make sure that you’ve fed your leaven (starter) 8 hours prior to mixing. You can do this by feeding the main starter or by creating a sponge (an off-shoot of the main starter) in a separate bowl. I like to feed my starter using two parts flour and one part water. It seems to result in a good stable consistency. Aim for a greek yoghurt-like consistency, not a watery consistency. You can feed the main starter 1 cup of flour and half a cup of water and leave it sit covered for 8 hours, for example. Or, to make a sponge, take 1/2 cup of starter out of the main container and add 1 cup of flour and half a cup of water. If you end up with more than a cup of starter in your sponge, put the remainder back in with your mother starter.

Step 1. Mix and autolyse: Combine the water and leaven (starter) together in a large bowl and mix it gently with a spoon or whisk. Mix the flour and salt together in a separate bowl and then combine with the liquids. Mix the wet and dry ingredients together by hand or in a mixer. Cover and let stand for an hour (autolyse).

Step 2. Stretch and folds: After the 1 hour of autolysing (initial mix-and-sit phase) take the dough out and punch it down gently with your finger-tips on a clean surface. You’re going to stretch-and-fold the dough four times at 30 minute increments. This step allows the dough to strengthen and rise as the gluten structure forms. You’ll notice that with each stretch-and-fold the dough becomes more elastic. Use a timer if you want to remind yourself of when the next stretch-and-fold step takes place. For each of the four stretch-and-folds you can treat the dough like a ‘square’. Take one side, or one corner, and pull it over towards the opposite side as in the image to the left. Do this for all 4 ‘corners’ or ‘sides’ of your dough. After each stretch-and-fold, cover the dough using a clean tea-towel or an overturned bowl and leave it sit for 30 minutes each time. Do this step four times!

Step 3. Once the four-step stretch-and-fold steps are complete, shape the dough into a ball. Try to gather the seams underneath the loaf so that the top of the loaf is smooth. Take the tray or dish that you’re going to bake the loaf in and dust the bottom of it with a coarse ground flour or whole wheat bran. Place the shaped loaf into the baking dish.

Step 4. We’re going to follow a popular theory and use baking twine to create the linear grove along the side of the loaf. It’s difficult to say why the groove is there and how it was originally made but it does not appear to have been made by the lip of a circular baking pan, as the loaves are often misshapen or bulbous below the groove as well as above it. It seems logical that something was corded or ringed around the loaf so we’ll try this method to create the groove although I am not certain that twine would have made an efficient or cost-effective choice for the original bakers. Take the baking twine and measure enough to encircle the exterior of entire loaf at the mid-section leaving ample length left over to tie the twine into a bow. See the image to the right for an example of what it should look like. If the twine is of the thinner variety, double it in length. Don’t tie the twine too tightly around the dough, give it a bit of room but not enough for it to fall to the base of the loaf; the dough is going to rise around the twine creating a defined lateral groove along the side of the loaf. Once you’ve secured the twine and tied the bow, cover the loaf with a tea towel, and place it in a warm place in your kitchen to rise.

Step 5. Dust the top of the loaf again with the coarse flour or wheat bran that you used to line the baking dish. Get the sharpest knife in your kitchen (or a bread lame) and score the bread making four linear slashes, creating eight even sections on the loaf. We’re going to score this in the same fashion as we see the bread sectioned according to the archaeological record; see the images to the left and below as examples. Now, we can debate whether these sections were made by a knife, by a cutter, by a blunt instrument, or by twine but it is difficult to determine this from the carbonised loaves that have been excavated. It is possible that the original bakers may have used twine to define each of the eight sections of the panis quadratus but it does seem like a fairly intricate and tricky job to complete, requiring knots or loops at eight junctions on a cord that would encircle the loaf horizontally. For this recipe, we’ll use a knife. Making four slashes through the top of the loaf, cut approximately 1 cm deep into the loaf. There’s no need to go any deeper as the loaf will rise again a bit more during the initial baking process and create a nice score.

Step 6. Now we’ll work on a final added detail that will make this loaf of Roman bread a fait accompli: we’ll give it a bread stamp. Using a cookie cutter, a pasta stamp, or any clean circular, square or rectangular cooking implement that you have, gently press a depression into one of the sections with it. As I do not have a bread-stamp, I have chosen to use a few pinoli (pine nuts) to fill in the circular depression that I have made using a small cookie cutter.

Step 7. Let the dough rise now until it has risen to twice its size. The length of this part of the process is entirely dependent on the temperature of your kitchen and the humidity of the climate in which you live. It could take two hours or it could take 4 hours. Cover the loaf with a clean tea-towel or put it inside of an air-tight proofing environment. Keep an eye on the loaf and take note once it has doubled in size and the twine becomes embedded in the side of the dough. Make sure that the dough doesn’t sit too long and expire; this is where getting to know your own starter comes in handy. The more you bake with your starter, the more you’ll know how long it will go in the rising process before it expires and the loaf deflates. For a dough with this much flour, my starter has a life of approximately 8 hours from autolysing to baking time. So I try not to let the whole process exceed seven hours.

Step 8. Once the bread has risen fully, preheat the oven to 400 F / 200 C / Gas mark 6. Place a small pan of water in the oven as you preheat it and leave it there throughout the baking process. It will create humidity in the baking environment that will allow for a bit more oven spring as well as a durable and chewy crust.

Step 9. Bake for 40 to 45 minutes until the crust is a medium brown tone. Once the loaf is fully baked, remove it and let it stand and cool for an hour or so. Don’t cut or break the loaf until it has cooled to room temperature. The twine can easily be undone and removed by untying the bow. You can also carry the loaf around the house for a few minutes like a handbag, if you’re so inclined! Perhaps the perimeter twine may have been used to hang or carry the loaves?…

Give yourself a pat on the back and a nice mug of mulsum! You’ve done it. You’ve baked like a Roman! Now to tasting the bread: Get in there like a legionnaire and break the loaf with your bare hands and try pairing it with some other Roman flavours. Pairing this panis quadratus with accompaniments such as honey, strong olive oils, pepper, milk and fresh cheeses will bring out the sweet and earthy flavours of the wheat and bran as well as the tangy flavour of the starter. It’ll give you an opportunity to taste what it was the Romans tasted when they ate their daily bread during cena (dinner) or at dawn during ientaculum (breakfast) as they began their days.

The end result for this recipe is a stunningly beautiful loaf of Roman bread with rich flavours and a textured crumb that is on the slightly heavier side. There is something so enjoyable about making this recipe as well: It’s a lesson in good old-fashioned, honest hard work; it’s meditative; and it’s historical. Finally, the pay-off is just magnificent. This recipe for panis quadratus is something that I will be baking regularly in my home especially for special occasions. It’s steals the spotlight on the table and goes well with every meal be it breakfast, lunch or dinner. When I broke my first panis quadratus open, I swear that I could hear someone whisper ‘bonum panem fert‘ in my ear… I give good bread… But then again that might have been the mulsum talking!

Cena bene and good baking to you!

Did you try this recipe at home? If so, please feel free to leave questions, comments or suggestions below. You can also join the conversation and share photos on the Tavola Mediterranea Facebook page or Instagram page.

I’m utterly impressed by the article and the video and Farrell’s work.

I like baking, I make baguettes, bread rolls and gluten free bakery for a friend.

And there was a core sentence in the video:

“You don’t bake for yourself. You bake for your family, for your friends.”

That’s what I do.

Respect for that great woman.

Thank you, Stephan! You are a kind human being! 🙂 – Farrell

I know it’s been a while since this was published but I think a cord or wire makes the most sense. Roman’s has a special fondness for lead wire, which is quite reusable (and toxic, but they didn’t know). The wire likely served to prevent spreading and to allow the base of the bread to function like a trencher if needed. Bread trenchers (plates made from bread) were used in the early Middle Ages, possibly in continuation of a Roman custom… think of it like an old fashioned bread bowl

Test

I figured out how to post a regular comment now 🙂 Just wanted to say that this is a fantastic recipe and it’s always turned out amazing. This is defiantly my go-to sourdough bread recipe

Hi, sorry, I probably just read over it but what starter should I use?

I continue to read your posts with interest. I have a question which I posted when I experimented with making Roman Bread. I was wondering whether the string had a use, ie to carry the loaves, or to string them along a pole above the sales counter, and whether once in the home, they would be hung from the ceiling to stop mice from accessing them. Come to think the mice would have found a hole in the ceiling and down the string. I wonder what your thoughts are on this.

That’s a wonderful theory. We’ll never know though, as no written evidence was left to describe this. – Farrell

I tried baking the bread but it came out rock solid – is this normal or did I do something wrong?

Something wrong! Did you add yeast? Did you overproof it? If it fell flat as dough, it was overproofed. It should be inflated prior to baking. Give it another go or try the newest version! – Farrell

I have two questions

(1) do I have to use spelt flour or can I replace it with any other flour?

(2) can I take out of the baking dish and put on a pizza stone

(3)do I have to preheat the stone

Yes and yes. Whole wheat is fine and a hot stone mimics an oven floor beautifully as well. 🙂

Hey! I am making this with a friend for our Latin class.

I was wondering what kind of pan do you recommend for baking it?

Thank you!

Hi Haley! I would use whatever you have available to you as most folks won’t have a brick oven to bake it in. If you have a baking stone or a large ceramic baking dish, that’d work the best. If you have access to a large commercial oven or a ceramic or brock outdoor oven, just slide it onto the base of the ovem with a pizza or bread paddle. Post pics on the Facebook page too! I’d love to see how it turned out.

A Dutch pot / oven, or a casserole do a superb job.

Pre-heat the oven to its maximum say 250 C with the Dutch pot or casserole inside. It might take 45 – 60 minutes.

Place the dough on a generous sheet of baking paper.

Remove the pot casserole from the oven and remove the lid.

Now, gather the corners of the parchment paper up so that it forms a sling and lower this into the pot/Dutch oven.

Leave the parchment in place and give the top of the dough a misting of water. This will help the loaf bloom and oven spring. (The loaf expanding in the pot).

Replace the lid. The paper will not burn.

Immediately turn down the oven to 220 deg. C

After thirty minutes remove the lid and, if you like, pull the paper out leaving the loaf i the pot.

Return to the oven for a further 15 minutes to finish the bake and give the loaf a nice golden colour.

I finally got around to baking a loaf. I used a little more than half bread flour and the balance whole spelt flour, leavened with a culture I’ve had for more than 25 years. (I’m a semi-retired bread baker by trade.)

I duplicated the groove around the edge by placing a disk of one half the dough on tip of another. I think that this is the simplest explanation. All of the others seem complicated and to no purpose.

I divided the loaf into eight sections by docking the risen loaf all the way to the bottom with a metal pastry scraper. Again, this seems to me to be more logical than slashing the top as it allows the finished loaf to be broken into more or less 16 equal pieces (eight wedges then separated top from bottom) of four ounces each,

The finished loaf looks just like the ones in the mosaics and, taking into account the carbonization, the one from Pompeii. Since it doesn’t appear that I can post photos, I will PM them to you.

Hi Jeff! Go ahead and post this to Facebook. The photos area beautiful!

Hi Jeff,

I am making the recipe with my daughter for her Roman homework project. Separating the dough into two discs makes perfect sense, but when you say you docked the risen loaf, does this mean after the final proving directly before the loaf goes into the oven?

I have only made bread with shop bought yeast before and would usually carefully make a shallow cut in the top of a loaf after the final proving to help it expand in the oven. I’m concerned if I cut it all the way through at that point I will knock all the air from the bread and end up with a discus!

When I saw the string I thought of this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ONWbvznkr7s

The band serves to restricts the spread of the dough in the oven – forcing the dough to rise upwards, rather than out to the sides. The less a loaf spreads outwards, the more loaves a baker could fit into their oven, which might make the extra work/expense of applying the string/band worthwhile. So many of these things start out as practical applications but evolve into stylistic choices – perhaps the string was once a necessary requirement but evolved into a aesthetic application as changes in backing technologies and the grains available might have made the string-as-band redundant?

(I didn’t have time to read all the comments so apologies if somebody already suggested this idea)

I know many users are suggesting loads of techniques, but couldn’t they possibly have used the same technique bakers use in modern day italy to make ‘rosette’ (in Rome) and ‘michette’ (in Milan)? I’ve read on a blog that sometimes using this technique will leave a ‘cut line’ along the borders of the bun as you’ll need to cut out the dough in excess before baking – here is an example on youtube: https://youtu.be/9dDoLAKr9M0?t=5m09s

I am totally behind you on this theory, Dario. One issue is that there’s nothing in the archaeological record that reflects this… nothing metal, anyways. Wood perhaps??? This is how my friend Gina and I make rosette as well. It all comes together with the ring on the outside and the divisions. One other issue though… sometimes the sections aren’t exactly even in size. It begs for further research and experimentation! – Farrell

Hi Sorry I’m posting this as a reply because I’m not sure how to leave a regular comment. I just wanted to say that this is my favourite sourdough recipe ever! I’ve used it for almost every loaf I’ve made and it always turns out fantastic. I usually just make two normal round loaves for convenience but making it look like the one from Pompeii is also very fun.

Hi, I just saw this video — is it possible they just cut the bread around, there was no string involved?

https://youtu.be/qQbqlCCeOO8?t=496

Hi! There are a lot of theories around the shaping and sectioning of the PQ loaf. I’ll be posting a follow-up post shortly to explore those further. It’s been very intriguing to hear everyone’s ideas on how these loaves were shaped! – Farrell

Another possibility explaining how the eight divisions were created is that the risen or partially risen loaf was divided with a knife or other edge pushed down through the dough. I do this when making small (300 gram) communion loaves. I use a dough scraper that is nearly as wide as the risen loaf and make two docks in the risen loaf at right angles. The loaf partially collapses but regains most of its volume from oven spring at the beginning of the bake. The finished loaf has a symbolic cross and can easily be broken by the celebrant with the words “This is my body broken for you.”

Hi Jeff! There’s been a lot of discussion around this in various forums this past week. I’ll be posting a follow-up post to explore all of these theories. Stay tuned and thanks for reading and commenting! – Farrell

What a great article! Thank you for this. So much information. I’ll be using the expression “gives good bread” as soon as I get a chance.

Thank you! I’ll be posting a follow-up in the weeks to come. More Roman recipes as well. – Farrell

larsiusprime at Hacked News suggests that the top and bottom were two separate balls of dough stacked on top of each other, explaining the groove.

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=15726244

The Byzantine Prosphora is similar. When Rome was sacked, people moved to Byzantium (imagine if California was bombed and people moved to New York). Byzantines still called themselves Roman. I think it’s probable that the same bread-making methods would transfer to their new capital.

That’s a fantastic theory. There’s a lot to explore here and I’m going to post a follow-up in a week or two given the high level of engagement and debate around the prep and form of these iconic loaves. I’ll spesk to that theory as well. Stick around and thanks for reading and commenting! – Farrell

Great article. Really enjoyed reading it. ?

Thanks Nick! There’s more where that came from. – Farrell

Could the string have been used as a way to ensure size consistency? The string would then be pulled off after baking and reused.

Hi! This is the 6 million dollar question! I have been debating this with Dr. Ken Albala (University of the Pacific/Food History) as well. He feels that a circular pan lip made that lateral groove but I don’t think that’s the case; if you google images of Panis Quadratus you’ll see other loaves that show the bottom and the top of the bread are often the same size with a significant groove/indentation (in circumference) or the bottom portion of the loaf is sometimes larger. So no pan… I tend to think that it’s probably twine that’s being used because I think the pistrinae would’ve had to cool these loaves by the hundreds. Perhaps they were hung to cool? Perhaps the loaf was two slabs baked on top of each other? But then why only section the top slab? I definitely think they would’ve had size restrictions as grain was heavily regulated. But I don’t know if the lateral groove connotes a size specification. Thanks for chiming in on this! There’s more Roman bread posts coming soon. Cene bene! – Farrell

This recipe was such fun to make. The kids loved getting thier fingers in helping make the bread. Trying to picke the next recipe from this site to make. Trying to find the tomatoe and rice one but still looking.

Hi Don! Thanks! I’m really happy the kids enjoyed making this recipe. Here’s the stuffed tomatoes recipe you’re looking for: https://tavolamediterranea.com/2016/09/21/a-week-in-ravello-lemon-and-rice-stuffed-tomatoes/

There’s a search window at the top of the site that can help you find recipes faster. Happy cooking! Farrell

Having baked my own bread for four decades a couple things seem obvious to me. Tying the string around the loaf may well have been useful for cooling and storing the loaves as well as transporting them neatly and in an orderly and compact fashion to the customers who ordered them. The string groove also suggests that after breaking or cutting the wedges apart it would create a hinge like fold which would facilitate the opening of the wedge from the pointed end and filling it with some other food as if it was a small pie (sandwich). I like to imagine the children running out to meet their friends with a wedge of stuffed bread in their grubby little hands.

Hi Traci! I think a lot about production volume as well when I consider that twine may have been used to transport and store the loaves. That’s a fantastic hypothesis about slicing guidelines too once the section has been broken out! Thanks for reading and offering your interpretations! – Farrell

Is it possible that instead of a single loaf, the dough was divided into smaller portions and then all tied together with twine to create a whole loaf out of parts? That would explain the divisions, and the groove from the twine.

That is an excellent theory, Kathryn. There has been some conversation about this today on Facebook. Someone else also suggested ‘pull-bread’. I think it deserves some more research! It’s very puzzling and fascinating, isn’t it? – Farrell