Helen Delores De Franco was born in Weirton, West Virginia, to southern Italian immigrants, Josephina and Vincenzo De Franco, on June 5th, 1919. She graduated from Weir High School and worked as a teletype operator at the General Office for the Weirton Steel Division. In 1946, she married Donato (Daniel) Monaco, an Italian immigrant who had arrived in the United States in 1929. Eventually settling in Rialto, California, Helen and Daniel Monaco would have 10 children together between the years of 1947 and 1962, and one of these children would be my future husband, Sam.

Sadly, I never did get to meet my mother-in-law, Helen, as she passed away a few years before I met my husband. Instead, I take in the stories about how tolerant and wonderful this woman was from her adult children and my husband: Helen was a doting mother and a woman of deep faith.

During her lifetime, Helen taught catechism at her local Rialto parish and was known nationally as ‘The Rosary Lady’ during the period of increased US involvement in the Vietnam War. After a deploying soldier asked her for her rosary before shipping out from Norton Airforce Base, Helen took it upon herself to write hundreds of letters to convents all over the world appealing for beaded rosaries for all of the American soldiers shipping out to war. Over the next two years, she had received and distributed 16,000 rosaries to American servicemen as they shipped out to Vietnam.

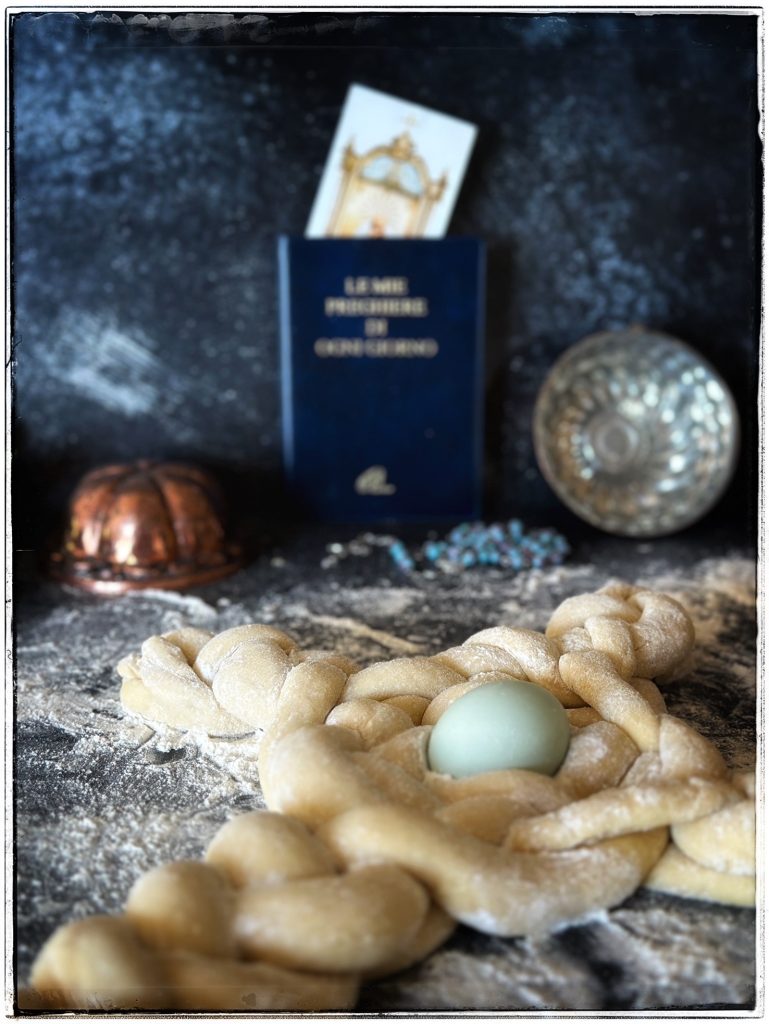

In addition to being ‘The Rosary Lady’, Helen was also a consummate cook. I myself have been witness to the reminiscent conversations about the traditional Italian food she made and these recollections generally start getting louder and more frequent around the annual holidays of Christmas and Easter. I would hear that at Christmas-time, Helen would churn out pizzelle and struffoli wreaths, and during Easter, she would make cuzzupe or cuddura cu’ l’ova: intricately formed Italian Easter sweetbreads that are adorned with coloured sprinkles and hard-boiled eggs. You see, Helen’s parents had emigrated to America in the early 1900s from Campania and Calabria, two regions of southern Italy, and while they may have left much of their belongings behind in the old country, they brought all of their religious and culinary traditions with them and handed them down to their children.

Helen has been gone for 16 years but some of her cooking traditions live on through her children and grandchildren, and through in-laws like me who take interest in the history and meaning embedded in Italian foods, and in particular the breads. Over the last few years, as Easter rolls around, my husband Sam has made it a habit of asking me to make cuddura Easter bread in memory of his mother, Helen. I oblige, not only to satisfy his sentimental yearning but to also satisfy my curiosity about the nomenclature, origins and symbolic meaning of these ornate religious breads.

Cuddura (the basic name of this bread type) is etymologically linked to an ancient Greek bread known as kollyra, which, I believe, belonged to a class of sacred, ring-shaped breads produced in the ancient Mediterranean. As the south of Italy was once home to the former Greek colonies known as Magna Graecia, it should come as no surprise that some of the Easter breads have names that are phonetically similar to the ancient Greek names for certain breads. And the names are many. Cuddura Easter bread is known by several different names throughout the regions of southern Italy: cuddura cu’ l’ova in Sicily; corrucolo or scarcella in Puglia; casatiello or tortano in Campania; piccillato or pannarella in Basilicata; and cuculi, cuddruri, sgute, ‘ngute, or cuzzupe (derived from the Greek word ‘koutsouna‘, meaning ‘doll’) in Calabria.

Exploring the ingredients of these Easter sweet-breads also echoes the bread- and pastry-making conventions of Italy’s ancient Graeco-Roman past: To begin, Easter cuddura is an Italian religious bread that is made of the finest and most pleasing ingredients, much in the same way that the Roman ritual pastry libum was. According to Cato, these sacred cakes called for white flour, cheese and eggs, and Varro explains that a portion of the cake was offered to the gods before it was consumed. Secondly, Easter cuddura is sprinkled with colourful candied sprinkles, just as modern struffoli are, which reflect the evolution of a Roman convention of sprinkling sweets with poppy seeds, as is the case with Roman globi. Lastly, smaller versions of these sweet-breads known as cuddureddi (or mustazzoli/mostaccioli), are also prepared with mosto cotto: a grape must syrup that the ancient Romans called defrutum.

Naming conventions and ingredients aside, the defining decorative feature that most Italian Easter sweet-breads share in common is the egg. Now, the concept of an egg being related to Easter isn’t a new one for most of us. After all, we spent our childhoods eagerly hunting for Easter eggs hidden in the bushes, thinking that a rabbit had placed them there for us. An egg atop of an Italian Easter bread somehow makes a bit more sense once you understand what it represents: it is a symbol of the resurrection of Jesus Christ. But the depiction of an egg as a symbol of resurrection didn’t start with the Christian church, or the generations of bread-makers of the Mezzogiorno: it started in Etruria.

Archaeologist, Lisa Pierracini, has described the presence of eggs in Etruscan funerary art, dating from the 8th to 3rd centuries BC, as prolific and as an iconic symbol of the afterlife and rebirth. D.H. Lawrence, on the other hand, viewed the egg within the Etruscan funerary context as a symbol of resurrection. Pierracini writes that ‘the egg holds life itself inside of its shell’, which explains why Lawrence also likened the eggshell to a tomb, and the interior of the egg to a soul and life-force that would eventually cause the shell to crack. Perhaps historic Christians, and Italian bakers of yore, would feel the same expression of the egg as a symbol of Jesus’s tomb and resurrection resting atop of a sacred foodstuff as old as agriculture itself: bread.

After the egg, a final and powerful acknowledgement of the resurrection is presented by the Cuddura di Pasqua and its various iterations: it is also meant to be consumed again on Easter Monday, known as Pasquetta, which is a national holiday in Italy. In North American or northern European settings, those who observe Easter will feast with friends and family on the evening of Easter Sunday, following a long Lenten fast. And this is generally when the festivities and Easter contemplations end. Not in Italy, however. Pasquetta is a day of family and feasting once again. It’s as if they have chosen to celebrate the resurrection of Christ one more time, breaking out the cuddura yet again after the dawn of this new day. And perhaps we can all learn something from this exceptional practice. After all, every dawn is a resurrection in itself: a chance to begin again with the rising son; to atone for the mistakes of yesterday; and to live — and love — to our highest potential. Just as every passing year gives Sam and me the opportunity to resurrect the memory of his mother, Helen, so that her Cuddura di Pasqua, her Graeco-Roman ancestry, and her faith can live again once more, even if only for the moment. With this perspective in mind, I wish you and yours a very happy Easter and a renewing Easter Monday, Easter Tuesday and Easter Wednesday… and Easter Thursday and Easter Friday.

Cuddura di Pasqua – a hybrid modern-historical recipe

Between the regions of southern Italy, Easter breads are prepared as both savory and sweet. This recipe combines elements of the ancient Roman sacrificial pastry, Libum, the use of grape must syrup, or mosto cotto, used in ancient Roman and modern Italian cooking, with modern renditions of cuddura cu’ l’ova or cuzzupe. This recipe can be made easily within a few hours at home and some steps or ingredients are optional. You also have the creative freedom to make simple or intricately formed loaves!

Ingredients – Cuddura di Pasqua (yields two loaves)

- 1080 grams (9 cups) of white bread flour

- 3 eggs (two for the dough and one for the wash) plus two or more eggs to adorn the top of the loaves

- 100 grams (1/2 cup) of butter

- 65 grams (1/2 cup) of cream, buttermilk, or ricotta

- 250 grams (3/4 cup) of honey

- 10 grams (2 tsp) of salt

- 225 grams (1 cup) of tepid water

- 20 grams (2 tbsp) of granular active dry baker’s yeast OR 100 grams (1/2 cup) of bread starter

- Optional: 8 grams (2 tsp) of vanilla extract

- Optional: Poppy seeds or coloured sprinkles

- Optional: Mosto cotto (as per the recipe below), to be used with the wash

- Optional: 55 grams (1/4 cup) of milk, to be used with the wash

Ingredients – Mosto cotto

- 1.2 kilograms of red or black seedless grapes

- 1 tsp (3 grams) of ground fenugreek

- A handful of diced fennel leaves

Implements

- A large bench scraper or sharp knife

- Parchment paper

- Basting brush

- Fine sieve or cheese cloth (for the mosto cotto)

Preparation

Creating the dough

- Begin by dissolving the baker’s yeast (active dry granules) or starter into the quantity of water called for.

- Let it sit for 5 minutes. This step can be skipped if you are using starter. If using baker’s yeast, wait until the yeast begins to foam on the surface of the water before adding in the remaining ingredients.

- Add the salt to the flour and disperse it evenly into the flour with your fingers.

- Crack open and gently beat the two eggs with a fork in a small bowl. Then combine them with the rest of the wet ingredients. Butter can be warmed ahead of time by leaving it on the counter. Gently blend the wet ingredients together in a mixer or mixing bowl with a whisk or fork.

- In a large mixing bowl or stand mixer, combine the wet mixture with the volume of flour and salt. Mix and fold well together until a cohesive ball of dough is formed. If the dough is too tacky or sticky, dust it with additional flour until you have a firm but flexible ball of dough. Cover and let the dough rest for 1 hour.

- As you wait for the dough to autolyse, put a small pot of water on to boil. Once the water is boiling, reduce the heat to medium and place the decorative eggs (depending on how many you want to use to adorn your loaves) into the water to cook for 10 minutes. Once 10 minutes has passed, remove the eggs and let them cool on the counter.

- After the dough has rested, turn it out onto a cutting board or clean work surface and knead the dough for 10 minutes. Cover again and let the dough rest until it doubles in size. This could take anywhere from 3 to 6 hours, depending on the temperature of your kitchen. The honey quantity called for in this recipe results in a slightly slower rising process as well. Place the dough in a warmer area of your kitchen to promote quicker rising.

Creating the mosto cotto (optional)

- Begin by washing and removing 1.2 kilograms of seedless black or red grapes from the stems. The sweeter the grapes, the stronger the syrup.

- Crush the grapes in a mortar or dice them quickly (using the pulse setting) in a food processor.

- Place the crushed grapes in a pot and heat to medium.

- Add the ground fenugreek and diced fennel leaves into the grape mixture in the pot.

- Reduce the grapes to half their volume, stirring periodically.

- Once reduced, turn the mixture into a fine strainer or cheese cloth draped over a colander. Allow the syrup to drain into a container or catch-pan below the sieve/colander. To extract the remaining syrup in the reduced pulp and must, place a dish on top of the mixture inside of the colander and then place something of weight on to the dish to gently press the remaining syrup out of the pulp and into the lower catch-pan. Leave this to stand while you prepare the dough for the loaves.

- This process will yield approximately 300 grams (approx. 1-1/2 cups) of mosto cotto.

Forming the loaves

- Preheat your oven to 350 F / 175 C / Gas Mark 4.

- Choose how you want to shape your loaves. There is a lot of creative license in this step. They can be shaped by studying the various forms of cuddura (for example: flat rings, twisted rings, birds or baskets) or by incorporating a braiding technique. I chose to incorporate the four-strand braiding of dough used in the production of challah: a 15th century bread form of Ashkenazi Jewish custom that is central to feasts on Shabbat. (Note: Challah is not consumed during the Jewish springtime religious holiday of Passover, which restricts the consumption of bread to that which is unleavened).

- Once the dough has doubled in size, turn it out onto a flour-dusted work surface and divide the dough into two equal halves. Each half will produce one loaf. Form the loaf to your liking!

- Using a four-strand braided set-up, I created one circular loaf and one crucifix, to honour my late mother-in-law, using two halves of the dough produced for this recipe. The video below demonstrates how each loaf can be braided like a circular or linear challah loaf. For both of my loaves, eight portions of dough were created from each half-portion of the total quantity of dough. For the circular loaf, all eight portions are equally split by the same weight or size. If attempting to make the crucifix, 4 portions of the dough must be smaller than the other four portions of dough as the smaller strands will make up the arms of the cross, and the larger strands will produce the trunk. This can be achieved by splitting the entire half-portion of dough into one portion that weighs 33% of the dough weight and another portion that weighs 66% of the dough weight. Each portion (33% and 66%) is then split into four equal portions of dough, creating eight portions in total. Use your kitchen scale or eyeball this portioning, if you dare!

- If choosing a braided dough form: wipe an area of your work surface clean on which to roll the strands of dough. Adequately damp surface and hands will be required to create the friction and grip required to roll the dough into strands. Place a cup of water and a bowl of flour nearby to use in the process. Starting from the centre of the dough, roll it back and forth drawing your hands outwards as you go, so as to elongate the strand. If the strand is sticking to the work surface, dust your palms lightly with flour and continue rolling. If the dough won’t roll and is sliding back and forth on your work surface, drop some water in your palms and on the work surface, creating a better grip.

- Once your strands are roughly the same length (don’t stress if they’re not…) you can move to braiding the strands. You can follow along with the video that I produced below, or google a bread strand braiding tutorial that will show you how to complete the process correctly. I challenge any one of you to attempt a 6-strand (or higher!!) challah braid! Share a photo on our Facebook page if you do!

- Lastly, place one or more eggs onto the upper surface of each loaf. Keep it an odd number of eggs (1,3,5) per loaf to follow tradition. This can be done by nesting them in between strands, pushing them into the dough, or by creating straps from leftover dough that can be crisscrossed over the egg to secure it in place.

Baking and washing the loaves

- Carefully move your fully formed loaves onto a baking sheet with a non-stick surface, or a sheet lined with parchment paper. Use a large bench scraper to get underneath the formed loaf to support it fully as you move it.

- Bake the loaves for 40 minutes in the preheated oven.

- While the loaves are baking, prepare the mosto cotto and egg wash to be brushed onto the bread shortly before it comes out of the oven. For this recipe, I have chosen to use the mosto cotto as a glaze as it lends an absolutely delightful sweet and anise-like flavour to the crust. During early experiments with these loaves, I discovered that using undiluted mosto cotto as a wash applied to the lobes of the loaf gave it a dark bronze colour. If making the cross-formed loaf, this may be an aesthetic choice that will produce a loaf that takes on the tone of darkened wood. I found that mixing half milk and mosto cotto together, however, produced a glaze that created a copper-like tone. The choice is yours! For each loaf, 65 g (1/4 cup) of mosto cotto and milk combined was an adequate amount.

- (Optional. Skip this step if not using a mosto cotto wash.) At the 40 minute mark, remove the loaves from the oven and, using a basting brush, gently brush the lobes, sides and upper surface of the loaf with straight mosto cotto or mosto cotto and milk wash. Try to catch any dribbles that run down the sides and smooth them out with the brush. Place the loaves back in the oven for 5 minutes.

- For the final wash (and glorious sheen!) beat the remaining third egg in a small bowl.

- Remove the loaves from the oven once again and gently apply the egg wash in sections with one hand while sprinkling poppy seeds or coloured sprinkles onto the washed areas of the loaf that are damp. Repeat these steps until the entire surface of the loaf is washed with egg and covered with sprinkles or poppy seeds. Bake again for another 5 minutes.

- After the final 5 minutes of baking, remove the loaf and let it cool fully on a cooling rack. If baking a circular loaf, check areas of the loaf surrounding the egg(s) to ensure that the dough has baked sufficiently around them. If it is paler than the exterior of the loaf, or feels a bit spongey when tapped with the finger, bake it longer, checking it every 5 minutes.

- Cool fully and serve!

Serving and eating

These breads can be prepared and served from Good Friday through to Easter Monday, Easter Tuesday, Easter Wednesday and so forth! The loaves can be sliced or lobes can be broken away from the loaf, if it is braided. However, I do suggest flaunting the crumb sliced, if you can, so you can admire the sweeps and waves that are a product of the braided strands of dough. Try the bread plain or with butter, or toasted with a nice hot cup of coffee or espresso on the side. I have been sneaking this bread for midnight snacks and breakfast since Good Friday so I don’t think anyone will be shocked if you do it too…