Quest’articolo è tradotto in italiano qui: https://tavolamediterranea.com/2020/04/27/preparando-il-formaggio-coi-romani-caseus-fumosus-velabrensis-la-caciotta-affumicata-del-velabro/

Good day, good readers and welcome back!! It’s been a veritable whirlwind this past month packed with travelling, airports, presentations, teaching, museums, hotels, new friends,…. and an award. Yes! An award! For those who did not see the back-to-back posts featuring far too many exclamation marks on my Facebook and Instagram last week: I was awarded the Best Special Interest Food Blog Award (Editor’s Choice) by Saveur Magazine on November 14th at the award ceremony in Cincinnati, Ohio. Oh, what a night!!! It is truly a wonderful feeling to have years of research, writing, photography, and development culminate into the best pat on the back you could ask for: an award and acknowledgement from Saveur Magazine. It makes all of the late nights of writing by the oil-lamp light and the back-aches from hand-milling worth every minute! I am filled to the brim with gratitude right now and I couldn’t be happier to press on through the year ahead to develop even more content and projects that shine a light on Roman meals, food preparation, and the archaeology of Roman cooking. But first, I owe YOU a huge thank-you. Yes, YOU, good reader!! I am looking at you right now… (and I can see what you’re wearing… and you look fantastic!). But seriously, thank you for being here, for reading, commenting, and cooking along with me for all these years. I love you guys. You’ve always been kind to me and that’s what makes producing this content a pleasure. THANK YOU.

So! With that on the table, today’s recipe is just for YOU GUYS, my readers, to say thanks for all of your support. It’s a doozy, though. I’ve been sitting on this recipe for over a month waiting for the right time to drop it… and that time is now, because this recipe is a special one. It’s a show-stopper and it’s steeped in incredible history rooted in the ancient food market district of Rome known as the Velabrum. It may be doable for some, and not for others, as it’s quite involved but that’s not going to stop me from telling you all about it. So get your milking pail and your apple-woods chips (or just a cup of tea and your readers…) because we’re going make Smoked Velabran Cheese, from start to finish. But first (as per usual…) a bit of history:

Cheese, like bread, has been a staple and a comfort-food in the human diet since time immemorial. Soft and hard varieties, as well as mild and pungent ones, make this food item a versatile and pleasing meal additive or enhancer that also stands brilliantly on its own with fruit, olives, bread, jellies, herbs and chutneys. Cheese-making originated long before recorded history with some theories suggesting that it originated in the Middle East and others suggesting it began in eastern Europe during the Neolithic Revolution with the spread of agriculture bringing it westward through the Mediterranean. It was during the early Neolithic period that humans began to move from hunter/gatherer lifestyles into the practices of farming, animal husbandry, and the keeping of livestock. With this development they discovered that domesticated animals could also be milked and not just used as draft animals, or sources of wool or meat.

The making of cheese had been documented by several ancient civilizations long before the Romans figured out how to make the dairy product on their own. In Egypt, in circa 2,000 BC, funeral murals documented the cheese-making processes. Archaeological evidence related to cheese-making has been found in Poland that dates to 5,500 BC. In addition to this, cave paintings found in Libya have also depicted the process of making cheese and these images date to 5,000-6,000 BC. On the Italian peninsula, the archaeology of cheese-making is evident in Etruscan bronze cheese-graters dated to the 5th c. BC, perforated to shred hard, aged cheeses. Mentions of various cheeses and the cheese-making process emerges in the Graeco-Roman written record from 800 BC forward in the writings of Hesiod (Works and Days), Homer (Odyssey and Iliad), and Varro (On Agriculture). By 50 AD, cheese-making by the Romans was made known in great detail by Columella in his writing De Re Rustica (On Agriculture – 65 AD).

Cheese-making in ancient Rome was a regular practice and many varieties of cheeses were prepared from fresh cheeses, similar to what we know as ricotta or cottage cheese, to early forms of aged and salt-brined cheeses. Columella tells us about cheese-making in De Re Rustica (Book VII, Chapter VIII) and tells us that:

“It will be necessary not to neglect the task of cheese-making, especially in distant parts of the country, where it is not convenient to take milk to the market in pails. Further, if the cheese is made of a thin consistency, it must be sold as quickly as possible while it is still fresh and retains its moisture; if, however, it is of a rich and thick consistency, it bears being kept for a longer period. Cheese should be made of pure milk which is as fresh as possible, for if it is left to stand or mixed with water, it quickly turns sour. It should usually be curdled with rennet obtained from a lamb or a kid, though it can also be coagulated with the flower of the wild thistle or the seeds of the safflower, and equally well with the liquid which flows from a fig-tree if you make an incision in the bark while it is still green……When the liquid has thickened, it should immediately be transferred to wicker vessels or baskets or moulds; for it is of the utmost importance that the whey should percolate as quickly as possible and become separated from the solid matter. For this reason the country-folk do not even allow the whey to drain away slowly of its own accord, but, as soon as the cheese has become somewhat more solid, they place weights on the top of it, so that the whey may be pressed out.”

Columella, De Re Rustica, BookVII

At Pompeii, it is possible to see a fresco on the back wall of a triclinium at the Casa dei Vettii that depicts fresh curds straining in wicker baskets. Ceramic cheese-presses have been found in many contexts throughout the Graeco-Roman world that are not only whey strainers but act as moulds themselves once pressing was applied. For this recipe, I used an exact replica of a Roman cheese press/mould that was made for me by an incredibly learned and talented potter in Rothbury, England: Graham Taylor of Potted History. Without this Roman food technology, this experiment would not have yielded the same results.

In addition to food frescoes and cheese-presses in Roman contexts, we can also find many references to Roman meals that referred to cheese, and smoked cheese in particular, especially in the writings of Columella, Martial and Athenaeus:

“The so-called boletinus bread is moulded into the shape of a boletus mushroom. The kneading-trough is greased, poppy-seed is sprinkled on the bottom, and the dough is put into it and does not stick to the trough while it rises. When it is put into the oven, some roughly milled grain is sprinkled on the bottom of the pan, and the bread is then put into it and acquires a fine color, like that of smoked cheese.“

– Athenaeus, The Learned Banqueters, Book III (3rd c. AD)

“Other eggs, cooked in warm embers, will not be wanting, and a block of cheese congealed over a Velabran hearth, and olives that have felt the frosts of Picenum.“

Martial, Epigrams, Book XI (1st c. AD)

“The cheese that has imbibed not just any hearth, not every smoke, but Velabran, that cheese has savor.“

Martial, Epigrams, Book XIII (1st c. AD)

In the passages above, we learn that the Romans weren’t strangers to smoking foods and that they were rather partial to smoked cheese. So much so that Martial mentions it twice! In both passages from Martial’s Epigrams, he mentions a variety of cheese called ‘Velabran’ and emphasizes the fact that smoked cheese, or cheese congealed over a Velabran hearth, is something to be desired. So, what the heck is ‘Velabran’ cheese, you ask? Let’s explore this a bit before we proceed.

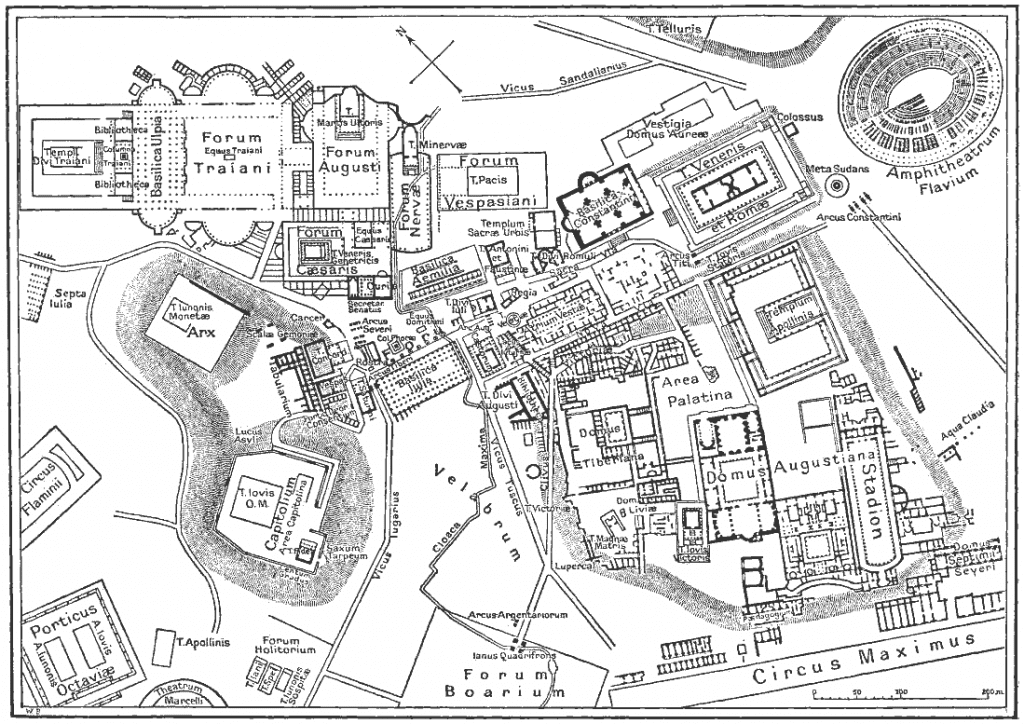

If you’ve ever been to Rome and you’ve taken a stroll down the lungotevere on the Tiber river towards Testaccio … and you come across a long line-up of tourists outside of Santa Maria in Cosmedin waiting to stick their hands inside of the sewer-cap that is the Bocca della Verità, you are standing in what was once of the most important area of ancient Rome related to food: The districts of the Forum Boarium and the nearby Velabrum. Today, it’s just another busy modern Roman neighbourhood filled with buildings, cars and buses… but if you look at the archaeological remains that are hiding in plain site in this area of Rome, it’ll all start to make sense. You are standing in the original heart of Rome; the real nucleus of the Eternal City.

The Forum Boarium, and the Velabrum, flank the Tiber river at the site of its oldest river port, the Portus Tiberinus. This port was established in the 6th c. BC when Rome was just a fledgling city, founded at a common crossing-place on the Tiber river. The Portus Tiberinus was where foodstuffs, and other resources and necessities, were offloaded from the river barges and redistributed for further transport inland, to local commercial vendors, to the state stores, or to private buyers.

The Forum Boarium, which sat between the Tiber river and the Velabrum, was once a bustling cattle-market. According to the documentary and archaeological records, the site was located on the banks of the Tiber River between the Palatine Hill, the Aventine Hill and the Circus Maximus. Forum Boarium began as a public gathering place to conduct agricultural and cattle trade. In time, the site also became a sacred public space that housed various temples and altars. Evidence of pre-Imperial Greek and Phoenician contact is visible at the site through the presence of the Temple of Hercules (2nd c. BC) and the Temple of Portunus (6th c. BC). The famed Via Salaria (Salt Road) also ran through the Forum Boarium using it as an entrepôt for salt coming upriver from the salt marshes at the mouth of the Tiber River to the city and settlements in the mountains to the north. Excavations at Forum Boarium in the late 19th and early 20th centuries AD revealed a system of walls beneath the current roadway, including a structure that was believed to have been a lupanar, or brothel, which supported the historical accounts of the area being run as a commercial district.

The Velabrum, immediately north of the Forum Boarium, was once a low-lying valley between the Capitoline and Palatine hills. To the north of the Velabrum was the Forum Romanum. While Plutarch informs us that the Velabrum was once a swamp that had to be crossed by ferries, and Seutonius informs us that processions of importance often made their way through the Velabrum, it is Plautus who gives us a short yet colourful image of what daily life was like in the market district of the Velabrum:

“In the Velabrum you can meet the miller or the butcher or the soothsayer or those who turn or give others the opportunity to turn.“

Plautus, Curculio, 2nd c. BC

“I left them after seeing that I was being made a fool of like this. I approached others, I came to others, then to others still: same story! All were acting out a conspiracy, like the oil-sellers in the Velabrum.“

Plautus, The Captives, 2nd c. BC

From what we read above, it sounds like the Velabrum was a bustling market-place full of hustlers, cons and food-vendors that was also quite possibly a gathering place similar to the Forum Boarium. If processions came through the Velabrum en route to the Forum or the Circus Maximus, it must have been a very busy place full of lot of people… People buying oil, milled grain (flour), bread, meat and cheese, if we are to believe Plautus and Martial!

So with that brief bit of history into two of ancient Rome’s early food market-places, let’s roll our sleeves up and make a block of cheese congealed over a Velabran hearth (or a Californian one for now…)! Before we get started, I realize that not everyone will have all the technologies to pull off the entire recipe as I did. You can make this recipe from the first step and then stop after the boiling phase, if you do not have a smoker or an outdoor oven. The finished product will still be delicious! If you do have a smoker or an outdoor oven, plan your preparation accordingly so that you can burn your wood to embers and reach an oven/smoker environment that is below 90 degrees F before smoking the cheese.

Let’s make cheese like the Romans!

Making Cheese with the Romans: Caseus Fumosus Velabrensis (Smoked Cheese)

Ingredients:

- 4 litres raw goat or cow milk

- Salt 35 gr+

- Rennet, or fig sap, or white vinegar, or two lemons

Implements:

- Cheese cloth

- Heat-resistant clamp

- Ceramic cheese press (optional)

- 12.5 cm (5 in) untreated wooden disk (optional)

- Screw-press (optional)

- Smoker (optional)

- Smoking rack (optional)

- Applewood chips (optional)

*Nota Bene: Be cautious about what kind of milk you buy for this recipe. DO NOT buy ultra-pasteurized milk or low-fat milk as it will not curdle, no matter how much you cry and yell at it. Save your money and your sanity: Buy raw milk or whole milk that is not ultra-pasteurized.

Preparing the fire:

- If you’re going to smoke your cheese once it’s set, start the fire early. It will take several hours to bring the heat down to a low temperature in the wood-fired oven or smoker.

- I used my wood-fired oven. There’s no need to buy a smoker if you have a wood-fired oven.

Separating the curds from the whey

- Begin by pouring the 4L of milk into a large cauldron pot. Heat the milk to a boil and whisk it as it’s heating. Be sure to keep the milk from burning to the bottom of the pot by whisking or stirring it as it heats. Once the milk reaches a boiling point, it will flare-up (fast!) and create a frothy dome. Turn the element off immediately or move the pot off of the flame at this point.

- Introduce your rennet, vinegar, fig sap, or lemon juice into the frothed milk. Typically, this can be done teaspoon by teaspoon until you begin to see a separation occur in the milk. See this recipe for more information on the various ways that Romans separated curds from whey during cheese-making. As the milk curdles, it will take on a yellow hue and curds will begin to form beneath the surface. If your milk is stubborn and will not curdle, try adding more of your separator (rennet, sap, lemon, vinegar), or bring the milk to a boil one more time. This will usually promote separation. Add more rennet, sap, lemon, vinegar after the second boil, if necessary.

- Once the milk begins to curdle, let it sit for 30 minutes and fully separate.

- This procedure will yield approximately 1.3 kilograms of curds.

Pressing the curds:

- I used my Roman ceramic cheese press/mould to strain and press my curds. Feel free to use cheese-cloth, a colander, and a heavy weight on top of the mass if you do not have access to a press.

- Initially, I placed the curds into wicker baskets to drain for a few hours. Then I placed the curds into my replica Roman cheese-press/mould to compress the curds and express more whey from the cheese. Then I used my screw-press and some custom wooden disks that I had cut to fit the mouth of my ceramic cheese mould.

- While there is no definitive evidence that screw-presses were used for cheese-making, this technology was used by Romans to press olives and grapes. It is puzzling to me that the Romans would use both wicker baskets AND durable terracotta vessels to simply drain curds in. I feel as if the terracotta mould is much more than just a bulky colander, so I used my mould as if it were intended to be used with a screw-press. It’s certainly strong enough to withstand the pressure.

- Place the curds in a cheese mould or a colander and press it by applying pressure or weight. Leave the curds to compress for 4 to 8 hours. I placed my mould and curds below the base of my screw-press and tightened it every 30 minutes for 8 hours. A significant amount of whey was expressed and the final compressed curds were quite firm and compact after 8 hours in the press.

Salinating the cheese:

- After 6 or 8 hours, there should be a fairly solid mass of curds in your colander or press. My press yielded a mass of curds that was feta-like in texture. I wanted to find a way to bind the mass while salting it so I decided to boil and brine the cheese in a salt bath.

- For this step, I decided to take some license and replicate sea-water to make a muria (brine) for washing and salting the curds. Salt was a prime commodity for Romans and it wasn’t always readily available. Apicius used sea-water for cooking boar. Sea-water was sometimes used by cheese-makers, historically, to salinate curds so I decided to try to replicate that for this salination process. It also firms fresh cheese without having to let it sit and age for a long period of time. On average, seawater has a salinity of approximately 3.5%, or 35 parts per thousand. Therefore, for every 1 litre of sea-water there are 35 grams of salt in it. I followed this formula when making my salt bath for the curds.

- Fill a small pot with 1 litre of water and add 35 grams (or 7 tsp) of salt. Tie the curds into cheese-cloth then twist and clamp the top of the cloth tightly so the curds are snug in the cloth. Drop the clamped cheese-cloth bag of curds into the boiling salt-water and turn it down low to simmer for one hour.

- Take the bag of curds out of the water and let is rest until it’s cool enough to handle. Once it’s cool to the touch, remove the cheese-cloth. You can shape the cheese further at this point, or you can chill it and serve it. At this point, the cheese will be firm, salted and ready to eat! But it’s not quite Velabran cheese yet…. so let’s see this through to the final stage.

Smoking the cheese:

- Now it is time to make this cheese into something that would have been sold by cheese-mongers in the Velabrum and consumed by men like Martial!

- Check the temperature of your wood-fired oven or smoker. It should be under 90 degrees Fahrenheit. This will allow the cheese to smoke nicely while not melting it at the same time.

- I used my outdoor wood-fired oven as my smoker. I started a big fire in the morning and it was cool enough by late evening, which was perfect, as I intended to leave the cheese in the oven to smoke for 8 to 10 hours.

- Once the oven was below 90 degrees Fahrenheit, I added some applewood chips to the remaining embers and swept them off to the far side of the oven.

- I placed my cheese, which was shaped into a round and placed on an iron rack, towards the other side of the oven, as far away from the embers as possible.

- I covered the oven door to limit the oxygen in the chamber and to keep the smoke in.

- I then went to bed and let Fornax do her thing with my home-made Velabran cheese!

The following morning, coffee in hand, I pulled the door to my wood-fired oven open. There, sitting quietly on the rack surrounded by ash was a pristine, beautifully smoked, block of round cheese. While staring at it, I was reminded of Athenaeus’ words when he described the colour of Boletinus bread: “When it is put into the oven, some roughly milled grain is sprinkled on the bottom of the pan, and the bread is then put into it and acquires a fine color, like that of smoked cheese.” Was this the fine colour Athenaeus was referring to?

The next step was to cut the cheese open and examine its density. This too was a satisfying result! The pressing, boiling, and smoking processes during the cheese-making turned a puddle of boring curds into a robust block of cheese with quite the durable rind. The core was solid, firm, and cut beautifully with a sharp knife. No sticking; no crumbling.

Finally, the taste test was what made me fall to my knees. The rind was tough, smokey and chewy… just perfect. The core texture was firm but creamy once it warmed up in your mouth. There was just enough salt and smoke to balance everything perfectly… and the smokiness wasn’t overbearing at all; there was hints of it throughout but it wasn’t dominant. A key observation was a slightly bitter undertaste in that comes from the use of fig rennet in the separation process. The combinations of the hints of bitter creaminess and smoked chewy rind makes this cheese flavour profile a distinctly Roman experience.

To me, this recipe was pretty key to understanding Roman flavour preferences. Romans enjoyed the taste of smoke. I do too. It’s strong and bold and it goes beautifully with sweet and nutty foods. When we consider other dietary items that Romans ate regularly, we can then try to place Velabran cheese in the mix to see how it would blend in with other daily Roman foodstuffs and I have to say that I think it’s a very sophisticated and fitting addition to the Roman daily diet. Especially when you consider the other flavours crossing the taste-buds regularly such as: olives; olive oil; figs; grapes; red wine; pomegranates; plums; dates; apples; coarse breads; whole-grain breads; garum; honey; carob… the list goes on! Many of these daily dietary items on the Roman table go beautifully with cheese but with smoked cheese, it’s a show-stopper! We’re looking at flavour combinations that are quite well-rounded, bold, and sophisticated indeed. I, for one, cannot wait to make this recipe again so I can hold a tasting to see how Velabran smoked cheese holds up when it is consumed in conjunction with other Roman foods. Until then, I’ll hold on to the words of Martial: “The cheese that has imbibed not just any hearth, not every smoke, but Velabran, that cheese has savor.” … and by Jupiter, does it ever!

Join in the discussion on our Facebook page or leave a comment about this recipe below on this page. If you’d like to chat in person with me or about any of the other recipes, you can join me at one of the The Old-School Kitchen live events taking place at a museum or venue near you. More information about this year’s events can now be found on the Events Calendar page.

How did you get the fig rennet? I want to try this recipe, but I don’t have a fig tree, so I’m wondering if this is something that can be purchased. Thank you!

From my fig trees! You can get rennet from several types of fruit trees if they provide the bitter white sap, similar to the sap seen in dandelion stems.

Love learning the history behind the food!

I pressed mine but am unsure of whether I need to crumble it before wrapping in muslin and boiling in the salted water; to then re-shape it into the round as you have done. Is that right? And thank you again for sharing the stories behind the making!

Had a long time interest in the ancient world but not found much in the way of food, my other passion. Will be making some of the recipes I’ve looked at

Happy to hear this, Mike. Welcome! – Farrell

Hello,

I’ve just had a go at making your Velabran cheese (up to the point of smoking..I’m not sure if the boyfriends up for letting me buy a smoker just yet!) and I was curious as to if you knew the benefit of boiling the cheese in the brine? A lot of cheese making websites I was looking at tend to just refer to soaking the cheese rather than boiling.

Thanks for all the hard work you’ve clearly put into this website, I’ve thoroughly enjoyed reading through it, and am thoroughly enjoying trying some of your recipes too!

Dan

Hi Dan! I boiled mine as it helped bind the curds into a solid mass and salt it as the same time. Similar to when you make mozzarella: you seperate it and then submerge it in a hot water and salt bath to stretch it and bind it back together again. how did yours turn out? Post it on the Facebook page so we can see it!

Thanks very much, alas I’m not on Facebook but I was pleased with my cheese, quite a mild, milky flavour and a sort of creamy firmness. Turned out well for a first go and will definitely make it again. ?

Is there any evidence that they aged the cheese as well?

Absolutely! The writings of Columella. 🙂

I was making ricotta this weekend and played around with the amount of liquid and salt I wanted in the finished product and this article is exactly what I needed to confirm that if I pressed the curds enough that more could be done to them! I’ve never brined before and your instructions are easy to understand. I already smoke foods, so I will now try smoking cheese based on your experiment! I’ve had success with your bread recipes in the past and I’m in awe of the work you put into this foodie/experimental archaeology endeavor!

Thank you Kyle! Come on over to the Facebook page and share your photos after you make your cheese! – Farrell