Good day, my friends! How are you managing in your part of the world? Are you healthy and well? I am well, myself. As some of you may know, I have taken this ‘forced pause’ during the COVID-19 quarantines to look for silver linings and focus on them rather than sulk and cry all day over when I will see the interior of an airplane again and when I will return to Rome, my home away from home. Lately, I have been gardening, baking, reading, writing, and swimming with my duck, Vera, who moved in 3 months ago and shows no signs of wanting to leave. Last I checked, we were 2 1/2 months into the California state COVID-19 lockdown, we’ve all gained 10 pounds, and the world has suddenly discovered that it is deeply enamoured with sourdough home-baking…. Huzzah! Interior crumb and mid-air ‘flour-tossing’ shots will soon be more prominent than photos of salads and Kylie Jenner on Instagram! (One can dream.)

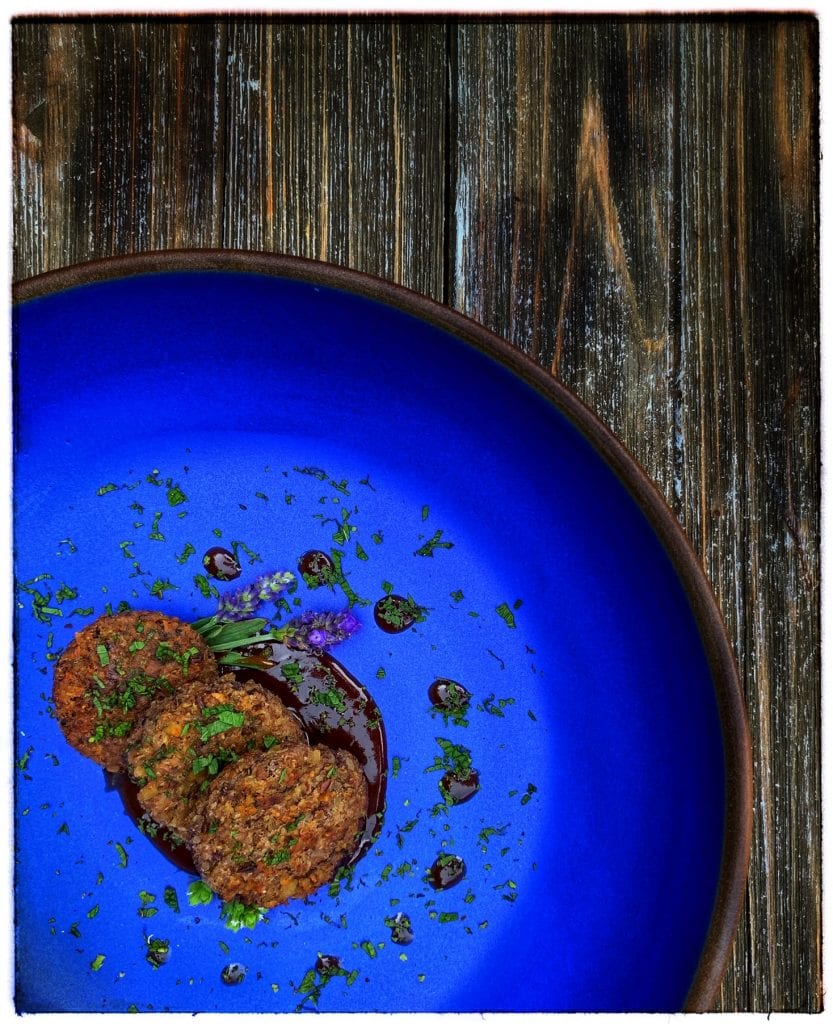

Photo: Farrell Monaco

In addition to sharing crumb shots with other bread-obsessed shut-ins — with the same pride we once had as children when sharing our Star Wars bubble-gum cards — I have also been working on some wonderful new recipes that highlight the Mediterranean Triad and the Roman diet; this recipe is one of them. I hope you’re up for trying some new bold flavours, and more importantly, an oenogarum that has now become the go-to sauce for glazing and accompanying meat dishes in my household. Only it doesn’t just go well with meat, it’s a show-stopper with vegetarian fare as well, as you will discover for yourself in this recipe. But before we roll up our sleeves and pull the amphora of fine Falernian wine from the cellar, let’s take a moment to explore some of the ingredients in this dish and their roles in Greek and Roman daily life.

‘The Mediterranean Triad’ is a term used to describe the three most prominent staples in the Classical Mediterranean diet: Grapes, Grains and Olives. These crops were central to Greek and Roman daily life in that they were accessible, versatile, and commonly used components of Roman meals, medicine, and sometimes skincare. Grapes were consumed as fruit, wine, must, syrup and sauces; grains were consumed as breads, pastries, porridges and digestive aids; and olives were consumed as fruit or processed into olive oil which was used for consumption, lamp fuel, and cleaning/moisturizing the skin.

We can see the Mediterranean Triad and its central nature to the Roman diet as associated archaeobotanical remains and processing technologies are well represented in the Roman archaeological record, such as: charred olive pits, grape seeds and whole grains; technological evidence such as rotary mills, olive and grape presses, and ovens or hearths; and pictorial evidence such as frescoes or reliefs. Another key archaeological element that demonstrates how much grape, grain and olive products were being transported and consumed throughout the Empire are the widespread distribution of Graeco-Roman ceramic transport amphorae in the Mediterranean and Northern European regions.

Amphorae pot-sherds can be found in abundance in archaeological contexts throughout areas that were once Greek and Roman territories. These vessels were in use as food transport containers for a period of approximately 1,000 years. The word ‘amphora’ is derived from the Greek word ‘amphoreus’ or ‘amphiphoreus’ and is described as a two-handled ceramic vessel that is meant to contain foodstuffs. The Greeks adopted the utilitarian shipping vessel design from the Phoenicians and Egyptians and began manufacturing their own versions of transport amphorae from the 7th century BC forward. From there we see amphorae begin to reach the Greek colonies in southern Italy from the 4th century BC onwards. We begin to see transport amphorae disappear from the archaeological record in Late Antiquity.

What makes amphorae an invaluable source of food-trade data in Roman archaeological studies is that they provide us with insight into contents, volume, and product origin. It would be impossible for archaeologists to discern how many olive products, for example, were transported into the city of Rome from provincial producers if we could only rely on long decomposed organic evidence. But when we have millions of ancient ceramic transport amphorae sherds, scattered throughout the former Roman territories, we have a much broader picture of the volume of foodstuffs that were being imported and consumed by Romans during the Republican and Imperial periods.

Now let’s talk about spelt. Spelt, or Triticum spelta L., is a hulled grain. But is spelt farro? Yes! But so is emmer and einkorn… All 3 being hulled grains and a proper pain in the Roman butt to thresh! Spelt, Emmer and Einkorn are known as farro in modern Italy, and this word is derived from the Latin word far that Pliny the Elder refers to in Historia Naturalis. You’ll often hear it iterated that bread in ancient Rome was primarily made from spelt, but this wasn’t the case. The two most popular grains in ancient Rome were barley and naked bread wheat, or Triticum Aestivum. And we know from the commercial Bakery of Modestus at Pompeii that bread wheat was found in the mills, not spelt. Spelt was indeed consumed, and it has been excavated in the Vesuvian region, but it was difficult for Roman farmers and millers to process in that it was not free-threshing in the same manner that naked wheat was. Spelt was laborious to work with which made it less popular than free-threshing naked wheat, which is why I always enjoy making recipes with spelt when I find it referred to in ancient Greek or Roman texts, or I see it represented in the archaeological record.

But what about beans, beans… the musical fruit?… and legumes? They should have called it ‘The Mediterranean Tetrad’, in my opinion, not ‘Triad’, considering the abundant evidence for beans and legumes in the Graeco-Roman archaeological and documentary records. Atheneus (Deipnosophistae, II) tells us of fava beans and chickpeas being consumed as snacks both freshly-picked or cooked, and Pliny the Elder (Historia Naturalis) provides a wealth of information on how to successfully grow and harvest beans and legumes, and how to preserve them as well. So today’s recipe is going to take a stand by incorporating that fourth staple of the Graeco-Roman diet, the lowly bean, along with grain (spelt), the grape (via wine) and a few quintessential Roman spices and condiments, as well.

This recipe also features the infamous, and much feared Roman condiment and flavour enhancer called ‘Garum‘. Rest assured, however, that much like the Hypotrimma recipe that I recreated recently, you will not detect any ‘fishiness’ in the finished recipe. On its own, modern garum-like products can be rather overwhelming, gag-inducing at times, but in the mix the pungent condiment takes most dishes to a level of well-rounded and bold flavour that is not experienced often, be they sweet or savoury dishes. Speaking of garum and fishiness: I’ll take a brief moment to say that I have been working with both of these brands of so-called ‘modern’ garum-like products (pictured below) and I wanted to note the distinctions between the two for those of you who already enjoy fish sauce and for those of you who want to try it. If you’re adventurous and you like bold, pungent foods… go for broke and try the Colatura Tradizionale (d’Alici di Cetara) made in Italy. It is powerful stuff and will linger in the room after you have used it. But you will NOT notice the ‘taste’ of the strong, fishy aroma in the foods that you incorporate it into as a flavour enhancer or salt additive. The Spanish brand, Flor di Garum, is milder but fishy still. It does not pack the same wollap as the Colatura does but it adds the same saltiness to the dish but with less aroma during the corking and cooking process.

You’ll also notice that the sauce accompanying this recipe is called ‘oenogarum‘, and it would serve us all well to know what that means so that we understand what ‘garum‘ actually is and what distinguishes it from ‘oenogarum‘. Garum itself is likely a term that was initially used to refer to the actual bits and bobs of blood and guts from fish remains that eventually went into fermentation vats, according to the grande dame of garum, Sally Grainger. The final product for consumption was called ‘Liquamen‘ and it was comprised of two grades of quality called: Muria and Allec. Muria being the finest, opaque grade; and Allec being the lowest, sludgier grade. The two words Garum and Liquamen were often interchanged in the Roman written record so it can get confusing! Oenogarum is a word that connotes ‘wine with fish-sauce’. Oeno from Ancient Greek oînos (wine) and Garum from Ancient Greek garos or garon (sauce made of fish). Oenogarum is simply a wine and fish sauce… which is what we are making today to accompany our rissoles.

Today’s recipe itself was recreated using a passage from Philoxenus of Leucas and two Apician recipes from De Re Coquinaria:

Philoxenus of Leucas (Fragments, 5th c. BC) references ‘a kneaded rissole of spelt-dough and boiled beans, fried crackly and gold in boiling oil‘ as one of many snacks spread out on a table accompanying a Greek symposion and a game of cottabus… and it instantly whet my appetite. One of the reasons why it intrigued me is because it was a late night snack meant to be consumed during heavy drinking, among men talking about manly things like hunting, politics and current affairs, whilst they are also playing drinking games, such as cottabus. This scene informed my choice to create an oenogarum for the rissoles.

Apicius’ De Re Coquinaria (Book II. Minced Dishes) also references a minced type of dish called ‘Isicia‘. The 1st c. AD Roman cookbook states that:

There are many kinds of minced dishes: Seafood minces are made of sea-onion, or sea crab-fish, lobster, cuttlefish, ink fish, spiny lobster, scallops and oysters. The forcemeat is seasoned with lovage, pepper, cumin and laser root.

Apicius, De Re Coquinaria (Walter M. Hill, 1936)

While some scholars translate Isicia to mean ‘croquette’, others translate it to mean ‘rissole’; and they’re essentially the same thing. Either way, Apicius’ versions of these fried fritters with minced fillings contain meat every single time. I wanted to try something simpler, however, and something that reflected the Mediterranean Triad, so Philoxenus’ version was chosen.

The oenogarum that I created for the rissoles is similar to the oenogarum that is referenced in Apicius’ De Re Coquinaria:

Wine sauce for fish:

Crush pepper, rue, and honey; mix in raisin wine, broth, reduced wine; heat on a very slow fire.

Another way:

The above, when boiling, may be tied with roux.

Apicius, De Re Coquinaria, Book X: In Pisce Oenogarum)

However, I added caraway to my oenogarum, as it was a well-known spice in ancient Rome, and it gave my oenogarum a bit more depth.

So, my friends! With all of that relevant knowledge in your back pocket, let’s pinch a few sestertii from Pater‘s change purse (he’s drunk and won’t notice) and let’s head to the maccellum to buy our ingredients. Here’s what we’re going to need:

The Mediterranean Triad: Kneaded Rissole of Spelt and Fava Beans with a Red Wine Oenogarum (Yields 100 rissoles)

Ingredients – Rissoles

- 1.1 lbs / 500 gr dry fava beans

- 1.1 lbs / 500 gr uncooked spelt (farro) grain

- The whites from 3 large eggs

- 4 tbsp / 60 gr of garum (fish sauce)

- 2 tsp / 10 gr of ground cumin

- 3 tsp / 15 gr of finely diced mint ( 1 tsp / 5 gr on reserve for garnish)

- 1 tsp / 5 gr cracked black pepper

- 1 tsp asafoetida (hing)

- Olive oil, lard or unsalted butter on hand for frying

Ingredients – Oenogarum

- 1/2 cup / 118 ml of red wine vinegar

- 1 cup / 236 ml of red wine

- 4 tbsp / 80 gr of honey

- 4 tbsp / 60 gr of garum

- 1 tsp / 5 gr of caraway seeds

Implements

- Mortar and pestle (or electric food processor)

- Large frying pan

Preparation

Rissoles

- Begin by soaking the fava beans and the spelt grain the day before, for 24 hours.

- The following day, strain and rinse the spelt and fava beans. Place them in their own pots and cover them with double the volume of water. They’re going to absorb a lot of it!

- Boil the spelt for 30 minutes, and then strain and rinse them.

- Boil the fava beans for 1 hour, and then strain rinse them.

- Place the spelt and fava beans together in a large mixing bowl or mortar and mash them fully until a cohesive mixture is formed. You can also use your food processor if you prefer.

- Add the egg whites, garum, ground cumin, diced mint (but save some for garnish!), asafoetida (hing), and the cracked black pepper. Stir it all together fully or use your hands to blend the mixture well.

- You now have the mixture for your rissoles. N.B.: I did not use bread crumbs or pastry for the exterior of these rissoles as they do not contain fatty meats, and are partially comprised of mashed spelt… so there’s more than enough starch to create a crispy exterior during frying.

- Place olive oil, or lard, or unsalted butter in a pan and heat the pan to medium-high.

- Use an ice-cream scoop or a large melon baller and scoop out uniform balls of rissole mixture. Flatten the ball into a small patty on your palm and place it in the pan. You may have to refill the pan with oil/lard/butter as you go, so do as many as you can in one go.

- Fry each rissole side for approximately 5 minutes or until is becomes a crisp, golden brown. Then flip it over and fry the other side.

- Place the fully fried rissoles on a clean tea-towel or paper towel to absorb any excess oil after frying.

Oenogarum

- Combine the red wine vinegar, red wine, honey, garum, and caraway seeds in a saucepan or pot and heat it on high.

- Bring the mixture to a boil and whisk it as you go.

- Reduce the heat to simmer once the alcohol has burned off and the honey is melted fully into the wine.

- In a pan or shallow pot, create a roux with equal parts butter and flour. I used one tablespoon of flour and one tablespoon of butter.

- Heat the pan to medium and slowly blend the flour into the butter with a whisk until it’s smooth.

- Bit by bit (about 1/2 cup / 120 ml at a time), incorporate the wine and honey reduction into the roux in the pan and mix it gently but continuously with a whisk. If flour lumps form, lower your heat a bit and whisk them out.

- Keep whisking until the oenogarum thickens and once it sticks to the whisk, turn the heat off and let it stand.

Plating

- As the oenogarum cools, it will thicken. Use a large spoon or a baster to place a large dollop of the oenogarum on top of a serving plate. The sauce is thick enough to stay put as well as support several rissoles that you can plate on top of it. In my opinion, it’s much more presentable this way too.

- Crown the oenogarum with 3 to 4 rissoles and then garnish the rissoles and the plate with the remainder of the diced mint and whatever you see fit to add… and serve!

- Take a bite, savour, and then get on your knees and thank Demeter and Kore, and Ceres and Persephone, and Saturn, and Dionysus and Bacchus for the bounty that went into this recipe and then go in for seconds… because you can’t eat just one!

The end result of this recipe was a very enjoyable dish that presented some pretty unusual and very pleasant flavours. The rissoles are pleasing as they’re crispy, filling, and satisfying morsels that can be consumed in quick succession. The oenogarum takes the cake, however, as it perfectly complements the nutty, wholesome flavours of the spiced bean and spelt meal in the rissoles with a weighty, bold, sweet and tangy sauce with a hint of caraway that opens it all up slightly… And the mint makes the entire dish brighter, fresher-tasting… like spring. The entire package is bold, comforting and refreshing at the same time.

While I was devouring my first batch of freshly made rissoles, I was imagining what it would have been like to have popped a few of them back, dipped in fresh oenogarum, after a long night of drinking at a symposion or convivium. Then the thought dawned on me that Greeks and Romans had much better drunk-snacks than we do in the modern era! Here we are eating hoagies, curry chips, and nachos with liquid cheese poured on them while staggering home from the pub… and the Greeks and Romans were eating rissoles?!

Where on Earth did we go wrong?

Join in the discussion on our Facebook page or leave a comment about this recipe below on this page. If you’d like to chat in person with me or about any of the other recipes, you can join me at one of the The Old-School Kitchen live events taking place at a museum or venue near you. More information about this year’s events can now be found on the Events Calendar page.

Before you go! The World Bread Awards are asking for nominations for 2020 ‘Bread Hero of the Year’. If you enjoy this site, my Roman bread research, and the recipes that I post here, please consider taking five minutes to nominate me (Farrell Monaco) as your Bread Hero. You can do so by emailing [email protected] or by tagging any of my bread-related posts on Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter with: #BreadHero

Keep cooking it old school!