Good day, good readers and a happy April to you! Spring has sprung! The dawn of a new summer is just around the corner and many of us are starting to crawl out of a long winter’s hibernation, wrapping up a year of income taxes (yuck!), and getting ready for the new adventures that the summer ahead will bring! Who doesn’t love summer, right? The flowers begin to bloom, the garden starts producing and the days are much longer and filled with life-giving sunlight!

Spring and summer truly are my favourite seasons of the year as it usually involves three of my favourite things: gardening, reading, and recreating Roman foods. Summer itself tends to be a season of elective reading for me as well. By this I mean that I finally get to set aside my amphorae catalogues and burnt bread photographs for a spell and jump head-first into a juicy fiction novel instead! One that is full of captivating characters, fascinating settings, and storylines that hook me while I’m reading them and then linger long after I’ve put the book down. You know the type… the book that whisks you off the planet every time you pick it up and then plummets you into the nine circles of hell after you’ve finished it. The book that makes your whole family avoid you for weeks after you’ve put it down because you can’t stop staring off into space or bursting into tears at the dinner table because when that book ended you had to return to reality and say goodbye to those characters and those settings that you adored so much! One such book for me was Crystal King’s “Feast of Sorrow: A Novel of Ancient Rome” (2017). If ever there was a book that I wanted to eat or turn into a garment that I could wear forever, this was it.

King’s 406-page novel is set in the 1st century AD in the household of a wealthy Roman gourmand known as Marcus Gavius Apicius: a name that is synonymous with one of the world’s first recorded cookbooks. Who is Apicius? It is assumed that a man named Marcus Gavius Apicius was the creator or original compiler of the oldest surviving collection of recipes in Roman history: De Re Coquinaria (1st c. AD). The surviving written manuscripts of the Apician recipes date much later, however, as the collection that we study and refer to in the modern era was formally compiled and recorded in the Late Roman or Early Medieval period.

In the Roman documentary record, Apicius is referred to several times by writers such as Athenaeus and Seneca; he was said to have been an epicure who enjoyed the excesses of life and had food and dining standards that were almost impossible to meet. Pliny the Elder says the following about Apicius: “Apicius, the most gluttonous gorger of all spendthrifts, established the view that the flamingo’s tongue has a specially fine flavour” (Pliny, Naturalis Historia, X.133 – 77 AD); and “Apicius, that very deepest whirlpool of all our epicures, has informed us that the tongue of the phœnicopterus is of the most exquisite flavour” (Pliny, Naturalis Historia, X.68 – 77 AD). Marcus Gavius Apicius was clearly an intriguing figure, one whose tastes were respected, and one that many loved to write about in the ancient Roman written record. In the modern era, Crystal King took this several steps further by constructing an entire novel around fictional characterizations of Apicius, his family and staff, and a glimpse into what his life could have been like inside both his home and his social circles. Narrated by Thrasius, Apicius’ prized slave and favourite cook, King’s novel takes us into the heart of Apicius’ ambition: To win favour among the Roman political elite through food and extravagant dinner parties. More importantly, however, the novel takes is into the lives of all of the people around Apicius who work tirelessly to make his ambitions possible. Most of us know what ambition cost our dear friend Apicius and “Feast of Sorrow” doesn’t spare its readers any of the hazards that are part and parcel with rubbing elbows in the circles that Apicius circulated in. Of course, one of the most enjoyable aspects of this novel was that it was centred on Roman food preparation, daily life in a Roman kitchen, and dining practices. By now, you’re beginning to understand why I loved this book as much as I did… The Apician recipes from De Re Coquinaria were interwoven into the story, into Apicius’ plots with Thrasius, and were featured prominently in the kitchens and on the dining room tables throughout most of the novel. It was this delightful aspect of King’s novel that I had missed the most after I had put it down, so much so that after a few weeks of pouting I decided that I was going to try to revisit these characters again by recreating some of the recipes that were made in Thrasius’ kitchen. This recipe for ‘Patina of Pears‘ is one of them. You’ll also find it in De Re Coquinaria in Chapter 4, ‘Compound Dishes’, (2.35).

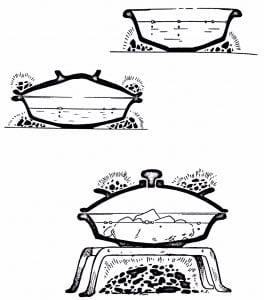

So what is a Patina exactly? That’s a question I asked myself several times when I first discovered this very versatile and popular ancient Roman dish in the pages of De Re Coquinaria. If we are to use analogy, it appears to be a sort of early form of soufflé that can feature a myriad of ingredients and can be made plain, savoury or sweet. In De Re Coquinaria alone there are 36 different Patinae recipes that contain anything from apples and nettle to fish and brains. But a patina isn’t just a dish that we can consume, it is also a type of ceramic pot that the dish is prepared in: a Patina pot. Grainger & Grocock (2006) and Hayes (1972) demonstrate beautifully how this Roman cooking technology was used to prepare this popular dish. The pot could be set directly into the embers or balanced on top of a trivet over the fire. If the lid was on during cooking it can be assumed that the patina was steamed somewhat, which would inevitably make it lighter and fluffier which is ideal for dishes that feature eggs. For this recipe recreation below, I used something from my arsenal that looked similar to a patina pot and it worked like a charm: a pudding steamer. Let it be known, however, that if I can have a few patinae pots formed and fired as close to the original technology as possible, they will likely bump my Le Creuset pots out of the pantry and into storage…

So! With that preface, let’s dust off our mortars and pestles and prepare a patina that would make the gods rejoice! Here’s what you’re going to need:

Apicius’ Pear Patina with Honey Fritters

- 9 large, ripe pears

- ¼ cup of sweet wine (dessert wine, ice wine) –or- ¼ cup of white wine sweetened with 1 tbsp of honey

- 1 tbsp of honey

- 1 tsbp olive oil

- 1 tsp of fresh cracked pepper

- 6 eggs

- ½ tsp of cumin

- ½ tsp of fish sauce (liquamen, garum, nuoc mam or nam pla)

Honey Fritters (Globi)

- 3 ½ cups (450 gr) of whole wheat flour

- 3 ½ cups (900 gr) of ricotta

- 3 eggs

- Honey

- Poppy seeds or fresh cracked pepper

- Vegetable oil, olive oil or lard

Implements

- Mortar and pestle or a potato masher

- Pudding steamer or a small casserole pot with lid

- Mandolin or sharp knife

Preparation

In preparing our pear patina and honey fritters, let’s refer to two different sources of text: Thrasius’ quote from “Feast of Sorrow”; and the actual recipes from De Re Coquinaria.

In chapter 2 of “Feast of Sorrow”, Apicius asks Thrasius that if he were to have any ingredient that he could get his hands on, what would he make? Thrasius replies with the following statement: “I would begin with a gustatio of salad with peppers and cucumbers, melon with mint, whole-meal bread, soft cheese, and honey cake….Then pomegranate ice to cleanse the palate, followed by a cena prima of saffron chickpeas, Parthian chicken, peppered morels in wine, mussels, and oysters. If I had more time, I would also serve a stuffed suckling pig. And to close, a pear patina, along with deep-fried honey fritters…”. In this passage Thrasius is referring to Apicius’ recipe for ‘Patina of Pears‘ found in Chapter 4 (2.35) and a recipe for honey fritters (Globi) found in Chapter 7 (11.6) in De Re Coquinaria. These recipes are comprised of the following ingredients and instructions:

Patina of Pears: Chapter 4 (2.35): “Core and boil the pears, pound them with pepper, cumin, honey, passum, liquamen, and a little oil. Add eggs to make a patina, sprinkle with pepper and serve.”

Honey Fritters (Globi)/Another Sweet Recipe: Chapter 7 (11.6): “Take coarse wheat flour, cook in hot water in such a way that you make a very thick porridge, then spread it out on a dish. When it has cooled down, cut it up like sweets and fry in the best quality oil; take them out, pour on honey, sprinkle with pepper and serve. A better result is obtained if you use milk instead of water”.

(Translation from Latin to English from: “Apicius” by Christopher Grocock and Sally Grainger, 2006).

Here are the steps that I took to prepare this recipe:

Pear Patina

- Core 8 of the pears and slice them. Boil them until they soften somewhat, but not too soft as to turn to sauce.

- Remove the pears, strain and cool them for a few minutes. Once cooled, place the stewed pears into a mortar or a mixing bowl and mash them together with the pepper, cumin, honey, fish sauce and olive oil.

- Add the sweet wine or dessert wine into the mixture which will be a substitute for passum: a sweet Roman raisin wine. If you have made your own passum, by all means use it in this recipe!

- Lastly, beat the eggs and add them into the mixture.

- Preheat your oven to 350 F / 175 C / Gas Mark 4.

- Take your remaining un-stewed pear and core it and slice it. Using a mandolin or a very sharp knife, cut or shave paper-thin sections from each slice of pear.

7. Coat the inside of your pudding steamer with a very light coating of olive oil. Wipe it on lightly with a rag or towel; do not pour the oil in and slosh it around. Keep it light.

- Line the inside lateral edges of your pudding steamer or casserole dish with the paper-thin slices of pear. Place them as evenly as possible. They should be delicate and moist enough to stick to the inside of the pot and stay in place.

- Gently spoon in the pear patina mixture into your steamer or pot gradually filling it and covering the pear slices that line the side.

- Place the lid on and bake for 1 hour or until the mixture no longer ‘jiggles’ and is solid or gelatinous in nature. Check your patina at the 30 minute mark and remove the lid if the mixture is still too wet or sloshy. You can check this by gently shaking it and looking at the centre of the top of the patina. This area will bake fully last.

- While the patina is baking, begin preparing and frying your honey fritters. Return to the next step below once your fritter dough is sitting or they’ve been fully fried and are cooling.

- Once the patina is fully baked, remove it and let it cool to room temperature. You can choose to let it cool fully overnight in the fridge before turning it over or you can let it cool to room temperature and serve it the same day.

- To present the patina, place the serving dish over the top of the steamer or pot and quickly turn it over. It should fall out of the pot with ease. If your pear slices did not adhere to the side of the patina perfectly, don’t worry. You can gently stick them back on to the side of the patina as they’ll still have some moisture and flexibility to them.

- Garnish the top of the patina however you see fit using what you have on hand in your fridge, your cupboards or in your garden: flowers; herbs; cracked pepper; pomegranate seeds; pear zest… the choices are endless but somewhat limited as you should be using ancient Roman resources.

- Once the honey fritters are done, surround the base of the patina with the fritters and serve!

Honey Fritters (Globi)

- It’s important to note here that I decided to follow Apicius’ advice and use dairy in this recipe instead of water. Apicius suggests making a porridge of the flour first and letting it cool as this strengthens the dough by allowing the gluten structure to build prior to frying. I decided to go with Cato’s recipe for Globi (honey fritters) as it too uses dairy as the softening agent but did not involve boiling or making a porridge first. Cato’s recipe, however, uses eggs to bind the dough even further.

- Place the flour, ricotta and eggs into a large mixing bowl and mix it together using your hand or a food mixer. Let it stand for 30 minutes.

- Fill a medium-sized pot or sauce pan to a two-inch depth with either lard, olive oil or vegetable oil and heat it for 10-15 minutes on medium. You’re dealing with hot oil on the stove at this point so use caution! Do not walk away from it and remember to keep the pot handle turned inwards and away from children or drunk people.

- You can test that the oil is hot enough by dropping a small teaspoon of fritter dough into it. If it bubbles and boils…. you’re ready to go!

- Lower the oil to Medium-Low. Using a teaspoon or the smallest ice-cream scoop in your kitchen, begin forming small balls of dough from the globi mixture and drop them gently, one by one, into the frying oil. You should be able to fry 10 or more at a time. It can take anywhere from 5-10 minutes per batch to brown the balls. This recipe produces about 40 balls of globi so be patient and fry them all until they are a dark golden brown. Note: Keeping oil on a medium to low temperature means that the inside of the ball will cook as fully as the outside.

- Line several plates or serving dishes with cotton or paper towels and spoon your fully fired globi onto them, batch by batch, so that they can cool and that excess oil on the balls can be soaked up as well.

- Once they are all fried, they can be arranged in any fashion that you like, dressed with warm honey, and sprinkled with poppy seeds or black pepper.

- You can serve these globi on the same dish with the patina or beside it. Whichever you choose to do, it’s always nice to have a side dish of warm honey on hand to dip the fritters in.

This recreation of Apicius’ ‘Patina of Pears’ recipe produced a dish that was delicate, fruity and yet very unusual in flavour. The patina itself is mild, fruity and fresh… just like the pears that went into it. The addition of sweet wine, cumin and liquamen did, however, take the flavour profile of this dish in a direction that borders on savoury and gives the dish some earthy contrast against the sweetness of the honey and the mild fresh flavour of the pears. Altogether, the flavour of the patina is just delightful but definitely different than what we are used to as a sugar-dependent culture that eats ice cream, sponge cake or biscuits for dessert. This is light, fresh, and natural tasting. The addition of cracked pepper also opens up the flavours in a manner that is savoury, sweet and very enjoyable.

The globi, well what can I say… these little darlings are designed to please and they always do. They’re deep-fried ricotta and wheat balls dipped in warm honey, for Pete’s sake! What could go wrong? Not a whole heck of a lot more than having to buy pants that are one size larger, to be honest. The honey fritters offer a crunchy and sweet accompaniment to go alongside the delicate, sweet and savoury patina. Together, the flavours of the fritters and the patina work beautifully and it’s genuinely difficult to refuse an additional serving of both.

Lastly, what has also resulted from this particular recipe recreation process is now a confirmed obsession with Roman patinae (both the pots and the meals). I am convinced that I can bake any ingredient into a patina now and my old friend Apicius wouldn’t argue with me on this either. 35 more patina recipes remain to be explored! Are you up for the challenge? I certainly am…

Buon appetito and good reading to you!

Crystal King’s “Feast of Sorrow: A Novel of Ancient Rome” will be released in paperback this week on April 10th. Be sure to make this book a part of your summer reading this year and consider a slice of pear patina as you read so that you too can taste the flavour profiles of Apicius’ time represented in a dish that was favoured enough by Roman society that is was recorded for all of us to enjoy 2,000 years later.

Feel free to leave comments or suggestions about this article using the comment form below.

Did you try this recipe? If so, feel free to join the discussion and post photos on our Facebook page.

i there! I made this for the first time today (love all your recipes btw- thank you!) but it came out a bit watery. How do I fix that? Should I have cooked it longer or for at a higher temperature? I tipped it out and emptied the liquid. Is there a way to upload photos?

Thank you so much for the histories, recipes, and help!

Hi Mazz! Did you remember this bit: “Remove the pears, strain and cool them for a few minutes. Once cooled, place the stewed pears into a mortar or a mixing bowl and mash them together with the pepper, cumin, honey, fish sauce and olive oil.” If the pears are too moist following straining, mash them up a bit a press them out before mixing eggs in. You can cheat and add 1/4 – 1/2 cup of flour as well (not in orig Apician recipe) to firm up the patina. Come join our Facebook page and post pics: https://www.facebook.com/tavolamed/

Greetings and Salutations:

We still have the fritter in American/Italian cooking! Some things just do not go away. Excellent delivery on the recipe and much appreciated!

Philip Rabitio

Fritelle and struffoli? I’m positive there’s continuity there! 🙂 Thanks for reading Philip! – Farrell