Good day, good reader! Are you healthy and well? I don’t know about you, but I’ve had enough of this COVID-19 pandemic already. Haven’t you? I miss Italy so much and I long to see the inside of an airplane and a hotel room once again. But alas, the gods are going to do what they’re going to do and I am just a mere mortal who must respect the COVID-19 virus, my health and well-being, as well as the health and well-being of those around me. So stay-at-home I stay. Aside from regular offerings of a non-human pharmakos on my domestic lararium, I am doing all that I can to stay fit, balanced, relaxed and reasonably productive during this incredibly strange time. I hope that you are being good to yourselves as well.

So, the last time I poked my head out of my fiendish lair of Roman food curiosities, every living human was producing homemade sourdough bread like they were the next bearded, tattooed, flour-dusted, post-punk, ‘artisanal’ baker on the avant-garde (or déjà-vu) bread scene… and the global grieving process was officially underway. You see, the sourdough bread baking phase of the COVID-19 pandemic’s early days was just the ‘denial’ stage for all of us; the first step of our collective grieving for the year 2020 and what it would become. For those who do not know the five stages of grief, they are:

- denial.

- anger.

- bargaining.

- depression.

- acceptance.

In the ‘denial’ phase, we thought: “Hmm… this COVID thing is a tad worrisome and they’re making us all stay at home… but we’ll be fine… let’s plant a victory garden and bake a mountain of sourdough bread!” Then the ‘anger’ phase kicked in, after two months stuck at home, and some of us threw down our aprons and took to the streets, pointing fingers and burning masks. Then the ‘bargaining’ phase kicked in, which saw many of us turn to old-time religion, by making small sacrifices and offerings, in an attempt to bargain with the gods and change the trajectory that we are on. And then came ‘depression’. This is the phase that we are in now, and for some of us it just kind of moved in one day, like an unemployed cousin, as we began to consider that maybe we won’t be out of the COVID-19 woods at any point during the year 2020. One minute it’s May, and you’re happily baking bread, and then the next minute it’s September and you’re still in the same adult onesie that you were wearing in May and you can’t recall if ‘summer’ even happened this year… This, my friends, is depression and it can really ruin your lockdown. But let us not despair! Let’s get up, get out of that adult onesie, and open the curtains because I have a remedy for this temporary phase we are in! Times like these call for bold measures and REALLY STRANGE ancient Roman recipes to shake things up, and boy have I got a weird and wonderful offering for you today!

During challenging times like these, I like to turn to experimental food archaeology projects that are unusual, involved, and off the beaten track; you know, something weird and wonderful. Why go for the low hanging fruit when you can explore the less traveled roads of Graeco-Roman archaeological, literary, and pictorial sources related to food and create something really interesting… and this recipe most definitely falls under this umbrella. It’s not a recipe for bread, nay, it is a recipe for an ancient Roman sourdough bread starter made from something entirely unexpected… and it is a BEAST! But before we get to cooking it old school, a bit of history first:

Bread starters in Ancient Rome

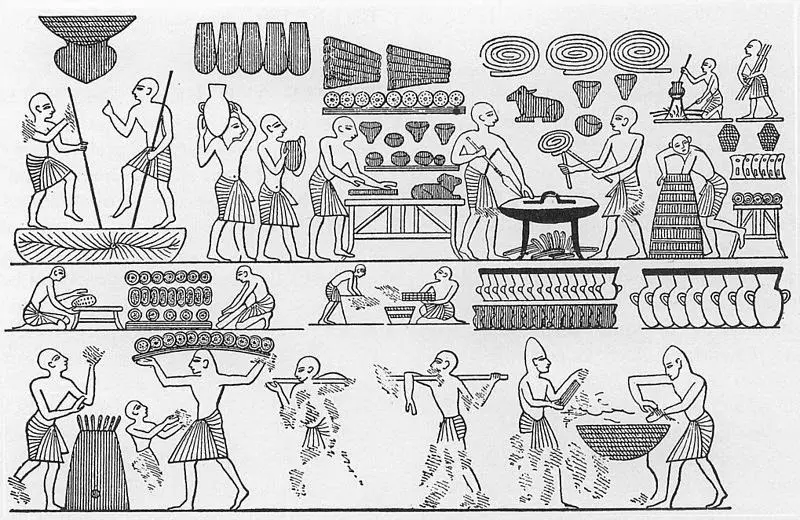

Cereal grains have been a staple in the human diet for over 14,000 years and evidence of early cereal grass cultivation and domestication has been detected in the archaeological record as far back as 8,000 BC in the Levant, or what is now present-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Palestine and Turkey. Farming and grain cultivation was one of the early hallmarks of the Neolithic Revolution which saw hunter-gatherer societies in the Levant begin to adopt sedentary (non-nomadic) lifestyles along with early farming and animal husbandry practices. It was during these early stages of the Neolithic Revolution that hybrid hunter/gatherer/sedentary farming societies learned to harvest and grind wild cereal grains such as einkorn, barley, rye, as well as legumes… and our taste for bread was born. Farmed in the Levant, einkorn was the first cereal grain to be domesticated; being a hulled grain, it would have been labour intensive and would have produced very filling porridges and unleavened flat-breads for these early populations. As domestication of cereal grains continued throughout history, preferred strains, such as free-threshing wheat, would be favoured and cultivated more frequently, eventually leading to the cereal grains that we bake bread with today.

The use of leavening agents in early bread-making was something that came along much further in the evolution of bread. Along with early beer-making, the ancient Egyptians are often credited with being the first civilization to ferment dough and bake leavened loaves in clay ovens, as opposed to over fire-pits, in hearths, or with the use of hot ashes, stones, pot-sherds or tiles. This fermented dough, or leaven, would be the fundamental ingredient for making leavened breads for millenia to come and we have written records of its use in the Classical Mediterranean through Pliny the Elder’s ‘Historia Naturalis‘ (77 AD). In Book XVIII, Pliny makes reference to leaven used in bread baking in the passage below:

“Millet is more particularly employed for making leaven; and if kneaded with must, it will keep a whole year. The same is done, too, with the fine wheat-bran of the best quality; it is kneaded with white must three days old, and then dried in the sun, after which it is made into small cakes. When required for making bread, these cakes are first soaked in water, and then boiled with the finest spelt flour, after which the whole is mixed up with the meal; and it is generally thought that this is the best method of making bread. The Greeks have established a rule that for a modius of meal eight ounces of leaven is enough.“

Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis, Book XVIII

But in the following passage, he speaks of two dietary ingredients that are often looked upon as lowly, both in the Roman world and in the modern era: barley and legumes. If you have a close look at what Pliny recorded next, you’ll see that he’s telling us something rather incredible:

“But when barley bread used to be made, the actual barley was leavened with flour of bitter vetch or chickling; the proper amount was two pounds of leaven to every two and a half pecks of barley….”

Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis, Book XVIII

What the hecking heck? Did Pliny just say what I think he said? Did Romans make bread starter out of legumes? Out of Chickling Vetch? Wha?… What the… MY HEAD ASPLODE.

Chickling Vetch

I know. It’s a great band name, isn’t it? “Chickling Vetch and the Angry Pistores! One night only… at the Colosseum!“… I digress. All jokes aside, let’s take a look at this little-known legume that Pliny speaks of.

Chickling Vetch (Lathyrus sativus L.) is a small, nobbly, white pea that is also known as grass pea, cicerchia, veccia, or chickling pea, and it belongs to the same species as bitter vetch. Thought to have originated in Turkey in the 8th millennium B.C., this drought-resistant legume was common in the Roman Mediterranean and was used mainly for animal fodder, according to Columella (De Re Rustica, II:19). In 1885, carbonised remains of chickling vetch peas were excavated from a domestic context at Herculaneum (The House of the Skeleton) alongside the remains of hazelnuts, figs, broad beans, walnuts, dates, lentils, and spelt grains. Perhaps, in urban settings, these peas were consumed regularly by both man and animal?

Pliny the Elder (Historia Naturalis, XXII:72) informs us that chickling vetch could cure anything from open sores to epilepsy. He also notes that the pea had a reputation for being hard on the bladder and kidneys. Pliny may have been warning of mild toxic effects attributed to the pea as he was well aware of the toxicity of bitter vetch and writes that ‘used as an aliment, this pulse is far from wholesome, being apt to produce vomiting, disorder the bowels, and stuff the head and stomach. It weakens the knees also; but the effects of it may be modified by keeping it in soak for several days, in which case it is remarkably beneficial for oxen and beasts of burden‘ (Historia Naturalis, XXII:73). Regardless of the effects, when processed correctly, the chickling pea provided Romans with a hearty legume that could feed the masses during times of drought and famine… and it made a damn good bread starter too! Chickling vetch is still consumed in parts of Italy today but it’s not as accessible or as popular as other common legume varieties are, such as chickpeas or lentils. So with that bit of history in our back pockets, let’s roll up our sleeves and make a legume starter!

Pliny the Elder’s Chickling Vetch Sourdough Bread Starter

Ingredients

- 500 g bag of dried chickling vetch (cicherchie) peas

- 500 g of barley flour

- water

- Optional: Raw apple cider vinegar (unpasteurized)

Preparation – Soaking and Fermentation

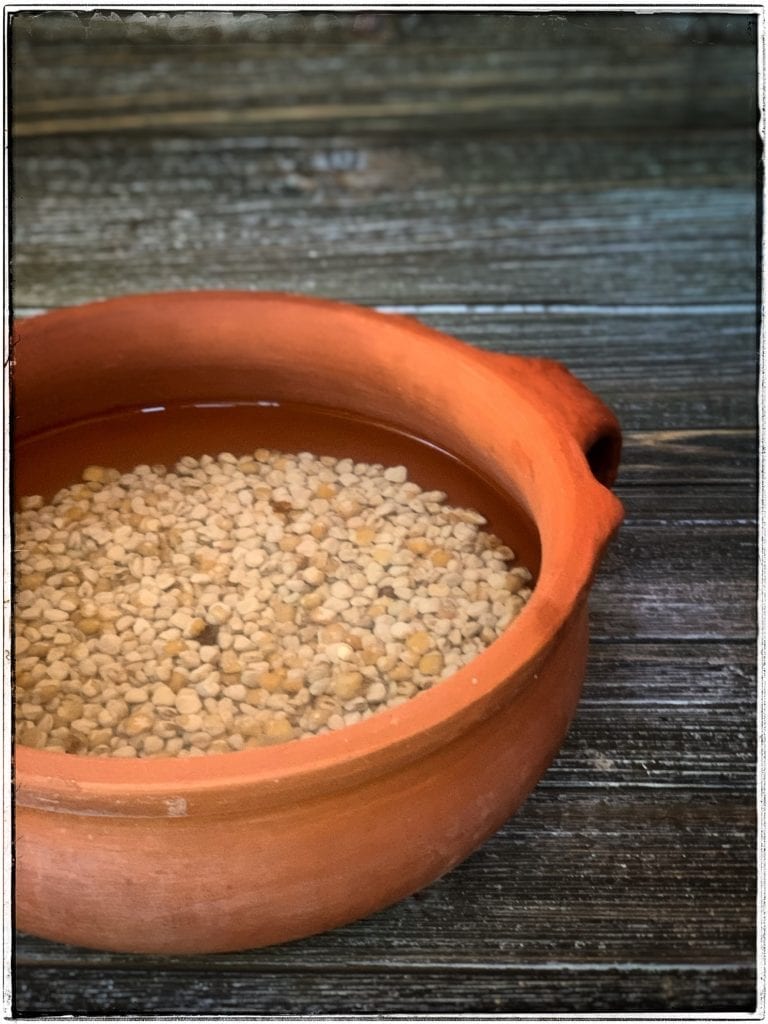

- During the preparation of this recipe, I listened to Pliny and erred on the side of caution by soaking my chickling vetch peas before I did anything else. The unprocessed seeds do contain a neurotoxin that causes something called ‘lathyrism’ which is a neurodegenerative disease which is caused by consuming too much of the legume for an extended period of time. As we are not consuming this for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, day in and day out, I am not overly concerned but I chose not to process the pea dry and I suggest you do the same.

- Soak your peas in water for 48 hours in a container with a lid. Make sure the water is covering the peas and change the water once at the 24 hour mark.

- After 48 hours, strain the peas and mash them using a mortar and pestle or your handy, modern, electric food processor.

- Place the mashed peas in a clean container and cover the meal with water so that it is submerged just below the surface. Cover the container tightly with a lid.

- Optional: You may opt to stir 3 tablespoons of raw apple cider vinegar in with the mulched peas and water as it will contain live microbial culture that will promote fermentation. The acid in the vinegar may also prevent mold and other nasties from developing during the early fermentation process. If you’re new to fermentation, consider this option.

- Leave the mulched peas to ferment at room temperature in the clean and covered container for 4 to 5 days. This period will vary depending on how warm and humid your kitchen is. Sneak a peek daily for mold!

- Once the fermenting mixture begins to get bubbly and smell ‘boozy’, it’s time to feed the starter and see what he’s made of!

Preparation – Feeding and Storing

- Once the mixture begins to smell boozy, remove 1 cup (235 ml) of the mixture and freeze the rest. You can use the remainder to grow more starter in the future.

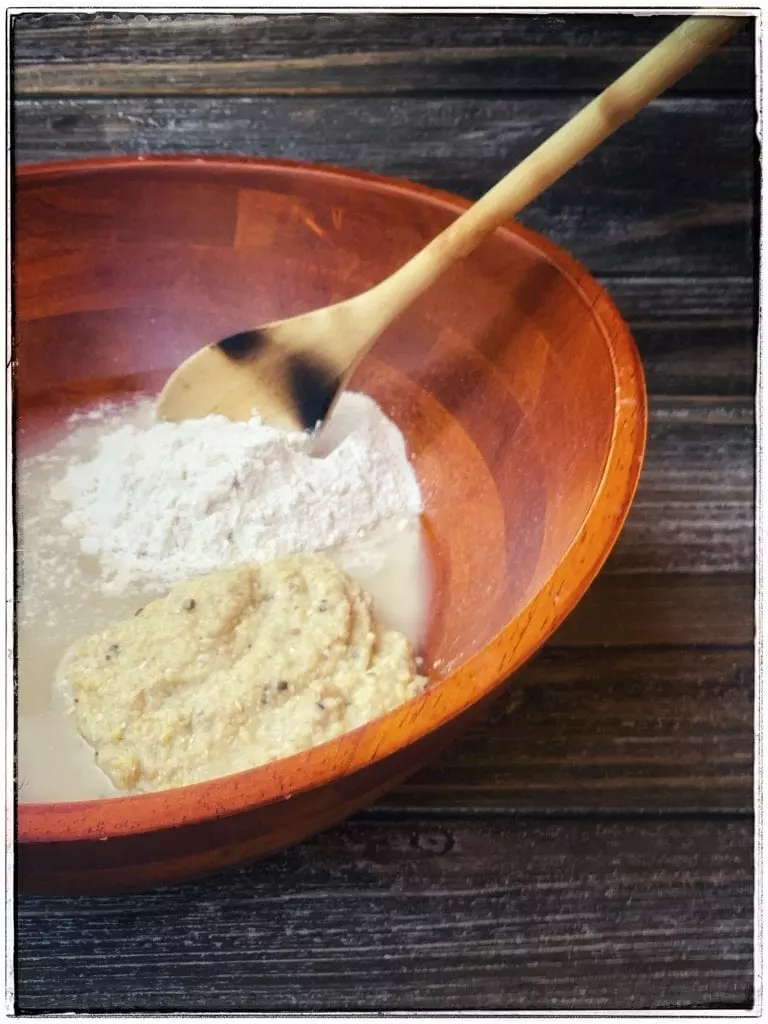

- You’re now going to feed the starter barley for 2 to 3 days to ‘activate’ it and get it working. We’ll do this with barley flour, which is in keeping with Pliny’s statement in Historia Naturalis.

- On Day 1 of feeding, get a new, clean vessel to work in and add 1/2 cup (118 ml) of water and 1/2 cup (75 g) of barley flour and gently fold it together. It will be soupy; don’t panic. Cover and let it stand at room temperature for 24 hours.

- On Day 2 of feeding, do the same: add 1/2 cup (118 ml) of water and 1/2 cup (75 g) of barley flour and gently fold it together. Cover and let it stand at room temperature for 24 hours.

- On Day 3 of feeding, check for inflation. The starter is going to appear chunky because of the legume meal present in it but keep an eye out for air pockets and inflation, which means the starter is activated and is ready to work!

- If your starter is still too soupy, take one extra day to bulk it up a bit by adding only 1/2 cup (75 g) of barley flour and gently fold it together, once again.

Preparation – Activation, Baking and Storage

- Once the starter has been activated, and you are observing significant inflation following feeding, you can bake with it at any point.

- Let it be known that when I fed this starter it took about 90 minutes for it to blow the lid off of the container it was being fed in. This boy is a BEAST!

- When you’re not using it, cover it and store it in the fridge.

- When you want to bake, bring the starter out the morning of and feed it equal rations of barley flour and water. You may also create a sponge by using a portion of the starter and feeding this portion in a container of its own. This is no joke: You will not need to feed this starter the night before baking. This starter is a madman; a beast that’s hungry for barley and it will blow the lid off of the container you feed it in within a few hours. I also top up the starter periodically with fermented vetch meal that I had stored as it gives the starter quite the boost.

- Note: If your starter is a bit lazier than mine, go ahead and feed it the night before. The longer you store it in the fridge, the longer it may take to activate it as well.

- Note: I suggest that you continue to feed the starter barley flour, as you use it, as it is in keeping with Pliny’s instructions. The marriage of the two key ingredients — legumes and barley flour — is clearly a match made in heaven. The two ingredients working together have created the most aggressive bread starter I have ever grown! Feed it both!

Now if you really want a Roman baking challenge, go ahead and try to make barley bread as per Pliny’s leaven-to-barley ratio below. That’s 660 grams of leaven (starter) to 13 kilograms of unmilled barley. Hmm… I think Pliny may have been hitting the midnight mulsum when he did this calculation!

“But when barley bread used to be made, the actual barley was leavened with flour of bitter vetch or chickling; the proper amount was two pounds of leaven to every two and a half pecks of barley….”

Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis, Book XVIII

Of course, you can use this starter to make leavened barley cakes, or you can use it to make sourdough bread along with depressed Don Draper and all the others who are still out there perfecting their tension pulls! The possibilities are endless and truly wonderful!

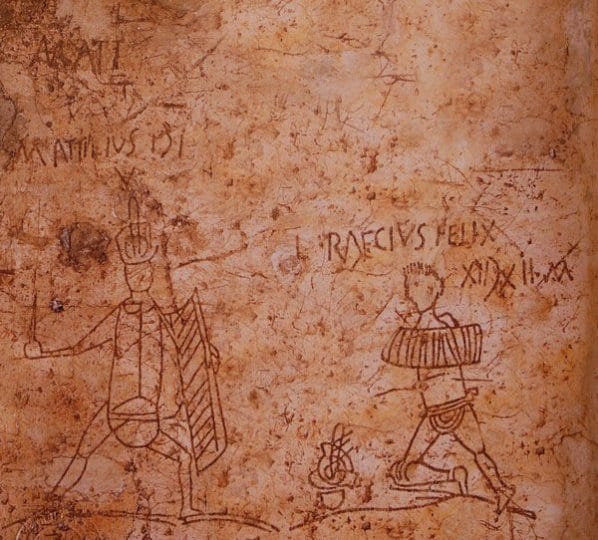

Lastly, as is the custom with all of my home-grown starters, I had to name this big boy and it didn’t take long before a name presented itself. Friends, Romans: I present to you: Marcus Attilius, gladiator. An unlikely hero and underdog,… fed with legumes and barley, just as all other gladiators were in ancient Rome. Attilius is truly a scene-stealer and a champion… and he inoculates a loaf of sourdough bread like a boss.

Most importantly, Marcus Atillius entertained and engaged me so much during the weeks that I began baking with him that before I knew it, I no longer had the COVID blues and I had moved closer to the ‘acceptance’ phase of my 2020 grieving process and I hadn’t even noticed! I mean, heck, with a sourdough starter like this blowing the lids off of jars and baking holey loaves like the one pictured below… I’ll be just fine here at home well into 2021! And you’ll be fine too. So get up and start soaking those peas! You’ve got a starter to make and bread to bake…

The science behind the starter! Learn more about legume flours during fermentation processes: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4618940/ Thank you to John Livesey and Dylan Thomas for sending this paper our way!

If you enjoyed this post, join the conversation on our Facebook, Twitter and Instagram pages! Thank you for reading and keep cooking it old school!

Hey Farrell! First I wanna just say I’m absolutely thrilled with your site! As an anthropologist who grew up in the restaurant industry this makes my heart so happy!!!

Second, I’ve been making your Arculata rings for a couple months now, my friends and family can’t get enough of them! My question is can I swap the 50g Sourghdough starter with 50g of this starter once it’s fat and sassy enough to work with, or should I stick with my basic starter and use this for other tasty treats?

Either way, absolutely love your work!

Always,

Saige

Hi! Yes, of course. Any starter will do the job if fed a day or two leading up to baking. Have fun! Thanks for the kind words!

What smell and look is fermented chuckling vetch supposed to have? I don’t know if it is ready to be feed or if we messed up.

Hi! To be honest, it smells a bit like sick when you begin to ferment it. This is from the bean meal fermenting. Once you begin to feed it with flour, it takes on the aroma of a starter. Read the piece in its entirety for warnings and missteps.

I love this idea! I’m in the midst of the process. I just soaked the chickling vetch for 48 hours and when I started to mash them, I noticed that they already had a kind of fruity even maybe moldy smell but I don’t see any mold. I let them soak on the counter for 48 hours because you didn’t specify whether that step should be done in the fridge or on the counter. Did I make a mistake? Thanks so much.

On the counter. The fridge doesn’t promote fermentation.

Hi! I recently found your blog when I stumbled over the NG article on panis quadratus – your blog is delightful 🙂

I have a few questions; I’m not a native English speaker though – my apologies if I missed any answer in the instructions:

– Regarding feeding the starter culture: Did I get it right that the starter needs to be continually fed with the soaked chickling vetch (not fermented), (barley) flour and water (~ 2:1:1)?

– I assume the starter later should be trained to the specific grain to use it for rye / wheat / spelt sourdoughs?

– Can I inoculate the mashed chickling vetch directly with existing sourdough starter?

Thank you and Cheers

Cade

Hi! Not continually fed, spike it with fermented vetch when it gets sluggish. Freeze the leftover fermented vetch though! I don’t train starters. I just feed them and see what they like and what they work with best. Sometimes you’ll have difficulties from one brand to the next and one flour variety to the next. It’s a process and a gamble. I think you certainly can spike an existing starter with vetch. Let me know how that turns out! Sorry for late reply! – Farrell

nice site

Ta!

This is very interesting, and I will try to track down cicerchia.

I have one difficulty with reproducing the Roman recipes, however: my wife is gluten-intolerant, so both wheat and barley flour is out.

Are there gluten-free flours (such as millet or rice) that the Romans sometimes used for bread?

And does the cicerchia starter also work well for those gluten-free flours?

Millet was in use but starters typically don’t do much for flours that are gluten free. It’s not strong enough to stretch and hold the air pockets. That said, if you make your dough, add the leavening agent, and leave the dough alone as it rises (don’t knead it as its pointless) you may get some rise if the dough is left to rise and then baked without being handled too much. This is how barley flour behaves as well – Farrell

I always enjoy reading your blog! I have been making natural levain bread with wild yeast water (often made from fruit) and sourdough over a year and, since I love Ancient Roman culture, I thought I should give this one a try. Unfortunately, I could not get chickling vetch, and so, I used chickpeas instead as you suggested in your response to one of the comments. It became really active only after one day, liquid and mixture of foam & some solid (mushed chickpea flesh/skin) were separated, but no yeasty smell like my other yeast starters. So, I just leave it for a while (I had to stir it to mix the separated solid and liquid, though). After a couple of days, it became very quiet; only some bubbles at the bottom but not much and no yeasty smell. I had to give it up after 9 days as I felt it would not be safe to consume it. I used a yogurt maker to keep the temperature of the starter consistently warm. Later, I discovered that the Turkish and Cypriot use chickpea flour to make bread starter, and the starter mixture activates only after 16 hours or so (!). Also, they use only thick foam on top. So, it may be that I need to try again to find chickling vetch or different legumes to substitute it, if I want to try this recipe again. Or, maybe I should try your the other Pliny the Elder’s recipe, levain with grapes instead ?. It was a very interesting experiment, and I thoroughly enjoyed it!

Hi! Initially you’re just seeing the gas from the beans. After a few days, start giving it fuel: flour and water… Try that and see how it goes! Once it eats, it starts to make alcohol and you’ll get that glorious boozy yeasty odour. 🙂

Thank you so much for the reply. I will try it and report back to you!

Hi Farrell! I just ran across this post and want to thank you for it. I was given a bag of Italian chickling peas in a Christmas box of goodies and wanted to do something special with them. Now I know what I’ll do! It’s rare to find many modern-day recipes using chickling, though I believe they are making making somewhat of a commercial comeback.

Thanks!

I just found your site and I am thrilled! I am both a dietitian and anthropologist, so this website is a terrific “marriage” of both of my passions. I love to cook, too, so I’ll be trying your recipes. Thanks for the fascinating information!

I am trying this with lentils and I will use whole wheat flour when I get there. Also I didn’t have apple vinegar, so I used alcohol. I am not following the recipe at all, I know. I just want to see if the legume starter idea works. I’ll report back.

Great blog! Same questions as one of the above, can I use different legumes?

Hi! And thank you! I would opt for chickpeas if you cannot locate chickling vetch!

Love your blog! would love to learn the art of Artisan baking SD bread for home use! there is not a single good bakery around here so sad????

Hi! I’ll be holding another bread-making class soon on Zoom. Be sure to sign up to the newsletter for updates!

This is a delightful read, well written and the connection to our pandemic quarantined lives and the need to up our cooking game is spot on. I am excited to follow you and eager to try your recipes. Bravo and much success!

Thank you Rebecca!

Love your blog! Thank you. Questions, can other legumes be used? Other flours?

Chicking Vetch…where can I order the bag from? I live in Southern California.

Try looking online or at local Italian imported grocery shops. 🙂