Salvete Amici! Non semper erit aestas….It will not always be summer. Alas, winter is coming…. just like it always does. And just like that we’ll put the bathing suits and flip-flops away for another year and get out our woolens and fire-wood instead. But that’s okay! Because good things come in all seasons and Roman cookery is a testament to that fact. It’s time for some comfort food, nay?

There’s nothing I love more than warm, filling, robust foods that stick to the ribs and give you enough energy to march your legion through the Teutoburg Forest… or at least keep you awake long enough to meet your writing deadlines… These foods usually take a bit of time to prepare, they heat up the kitchen and fill the sink full of dishes too, but the results are always so rewarding and this recipe is no different. This week’s offering is a veritable pas-de-deux of Roman cooking excellence: a recipe that welcomes winter with open arms as we explore the practical and comforting side of ancient Roman cooking as well as the creativity involved in Roman eating practices. We are going to pair Cato’s recipe for Tracta and Apicius’ recipe for Vitellian Beans and bring history to our tables once more. But before we get started, a bit of history first:

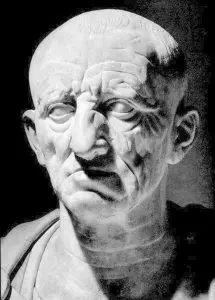

Who is Cato the Elder? Cato the Elder, or Marcus Porcius Cato (Marco Porcio Catone), (234 BC – 149 BC), was a respected Roman senator, soldier, historian and patriot who fought to preserve Roman culture and tradition in the face of Hellenistic influences in the late Republican period. Cato was no different than most Roman soldiers: when he wasn’t serving Rome he was working his land. Cato wrote his manual for agricultural life ‘De Agri Cultura‘ in 160 BC and, similar to his other writings ‘Origines‘ (168 BC), it lends a great deal of insight into Roman history, Roman daily life, and Roman food preparation. Cato offers his recipe for tracta in De Agri Cultura and it’s just as practical and filling as you’d expect the utilitarian flat-bread to be. You can read De Agri Cultura in its entirety online here.

Who is Apicius? Marcus Gavius Apicius is a figure in Roman history that many love to write about. In fact, Crystal King wrote an entire novel about him, his staff, and Roman cookery, in her recently released fiction novel “Feast of Sorrow: A Novel of Ancient Rome”… and rightly so, because he was quite the character.

Apicius is referred to several times in the documentary record by writers such as Athenaeus and Seneca; he was said to have been an epicure who enjoyed the excesses of life and had food and dining standards that were almost impossible to meet. Pliny the Elder says the following about Apicius: “Apicius, the most gluttonous gorger of all spendthrifts, established the view that the flamingo’s tongue has a specially fine flavor” (Pliny, Naturalis Historia, X.133 – 77 AD); and “Apicius, that very deepest whirlpool of all our epicures, has informed us that the tongue of the phœnicopterus is of the most exquisite flavour” (Pliny, Naturalis Historia, X.68 – 77 AD). It is believed that Apicius lived in the 1st Century AD during the reign of Tiberius, but the writings and recipes (more so loose guidelines) associated with his name weren’t published until the Middle Ages and later. While the Apician recipes, titled De Re Coquinaria, that have been scrutinised and studied for hundreds of years do indeed reflect accurate Roman Imperial food preparation and ingredients, it is often suggested that the recipes may have been devised as a tribute to Apicius, or Apician gluttony, as opposed to being created by his own hand in the 1st Century AD. The recipes outlined in De Re Coquinaria are some of the most scrutinised and tested Roman recipes in the documentary record and Fabam Vitellianam is one of them.

The first reason why I chose to interpret and attempt these two recipes, from two very different authorities on Roman cooking, was to highlight some of the simple, practical and wholesome flavours that were present in common, every-day Roman cooking; there’s no liquamen, no defrutum or dormice in these recipes but they’re delightful just the same. Another reason why I have paired these two recipes together is to demonstrate how tracta may have not only served as a flat-bread or soup thickener, but it may have also served as an utensil at the Roman table in both domestic and commercial settings. Utensils weren’t a dime a dozen in the Roman Mediterranean like they are today and forks weren’t even a reality yet for Roman diners! So how did they deal with messy soups, stews and cheeses without ample utensils? Well, Romans did have spoons and knifes but in a time when metal objects were just as precious as salt, most utensils were probably kitchen implements or personal items and other methods of ‘graceful’ food consumption may have had to be resorted to, especially when away from the home. It is often suggested that bread and tracta (hard-tack, laganum, lagana) may have been used to sop up messier foods and soups when utensils were not something that were readily available outside the home, in transit, or in the homes of the poor. I decided to test this theory and I was pleased to discover that there’s some weight to it. When you have completed this recipe you’ll discover, just as I did, that the two recipes go beautifully together, flavour-wise, and that each tractum is the perfect fabam delivery method from the dish to the mouth.

I have chosen to use fava beans for the fabam recipe as, quite frankly, I don’t think anything else could be more suitable. Fava (broad) beans have been grown in the Mediterranean region for over 8,000 years and it is a resilient crop that was easy to grow. Farro was chosen as the groat type to use in the tracta rusks as hulled wheat grains were also very common in Roman cooking and baking. Often referred to as ‘spelt’, farro grains are durable, flavourful and very filling. Farro grains would have been present in the Mediterranean for millenia before the Roman Empire and would have likely been as present on the tables of Romans as it is on the tables of Italians today.

So with that said, lets roll up our toga-sleeves and get cooking shall we, fellow coqui? Nota Bene: It’s a good idea to start preparing both of these recipes the night before you intend to serve them; it takes 12 hours or more to soak the beans fully and the same amount of time to swell the groats in water. Before preparing the recipes, check the ingredients below and submerge the beans completely in a large pot of water before you go to bed. Do the same with the groats in their own bowl or pot. When you return to the recipes the next day, change the water for the beans and get to work on the tracta first; it will require an additional amount of drying time and you can prepare the beans while the tracta is drying.

Tracta

To make tracta, Cato informs us of the following method in his recipe for ‘Placenta‘ (a tiered, cheese-based dessert used for ritual purposes), where he uses the tracta as a crust or pastry layer:

“Materials, 2 pounds of wheat flour for the crust, 4 pounds of flour and 2 pounds of prime groats for the tracta. Soak the groats in water, and when it becomes quite soft pour into a clean bowl, drain well, and knead with the hand; when it is thoroughly kneaded, work in the 4 pounds of flour gradually. From this dough make the tracta, and spread them out in a basket where they can dry; and when they are dry arrange them evenly. Treat each tractum as follows: After kneading, brush them with an oiled cloth, wipe them all over and coat with oil. When the tracta are moulded, heat thoroughly the hearth where you are to bake, and the crock. Then moisten the 2 pounds of flour, knead, and make of it a thin lower crust.” (Marcus Porcius Cato, De Agri Cultura (160 BC) – 76.1).

(Translation from: The Loeb Classical Library)

This is how I proceeded with Cato’s instructions after soaking the farro groats overnight and it worked out perfectly. I calculated my amounts converting Cato’s Roman pounds to modern grams/cups. A Roman pound is equivalent to approximately 330 grams and my interpretation of his recipe for tracta has applied those conversions. I found Cato’s recipe to be quite large, however, so I halved it and it made more than enough tracta for Apicius’ fabam. I added my own measurement of water to the mix when kneading the flour and groats as Cato did not specify. Perhaps Cato had too much mulsum the night before and forgot that tiny detail! Here’s what you’re going to need to prepare your tracta dough:

Ingredients

- 330 gr (1+2/3 cups) of dry farro or barley groats

- 933 gr (4+1/3 cups) of whole wheat flour

- 1+1/4 cups of tepid water

Implements

- Clean tea towels or wicker baskets

- Rolling pin

Following Cato’s instructions, I prepared the tracta rusks as follows:

Step 1. Soak the farro/barley groats overnight in 4 cups of tepid water.

Step 2. Drain the groats thoroughly in the morning and then smash them in a mortar, or a food processor, until they are the same consistency of a rough-textured porridge. No need to cream them, they’ll act as a binder with the flour and water when making the rusks.

Step 3. Mix the flour and water in with the smashed groats, bit by bit, and knead it all together. You can also do this in a bread mixer.

Step 4. Once all of the flour is mixed together with the groats, remove the dough and place it onto a cutting board or a clean work-surface. The dough is going to be very firm, and it should be, as you are making something similar to a Scottish oat biscuit. It’ll be tough, chewy, nourishing and robust once it’s ready for eating so the raw dough will reflect this texture as well.

Step 5. Flatten the dough out as much as you can with your hands. Use a cylinder, a bottle or rolling pin to flatten the dough as much as possible. It’ll fight back so do your best to get it down to approximately 1/2 cm (5 mm) or so.

Step 6. Brush the top and the underside of the dough with a fine coat of olive oil. Cut your tractum into a circle that will fit into the base of your drying basket or onto your tea towel. Take a sharp knife and section the tractum, cutting about halfway into the dough, into even sections. This will make it easier to break each piece of tractum off when you’re eating them with the beans.

Step 7. Repeat steps 5 and 6 for all of the tracta dough and leave them in a warm place to dry until each tractum is crisp and hard, showing no moisture or damp spots. If you’re in a rush, you can nudge them along and bake them gently for one hour on 250 F / 120 C / Gas Mark 1. IMPORTANT: It is an important consideration, in a modern setting, whether we should bake the rusks or not. They contain raw grain (uncooked farro), afterall. E. Coli outbreaks have occurred recently in some commercial flour products so it’s an important point to consider. The Romans may not have been aware of the possibility of E. Coli in their uncooked grain supplies but we have this knowledge at our disposal, thankfully, and it’s made our modern food preparation practices safer for it. If you are concerned about taking that risk, bake your rusks. You can bake the rusks for 1 hour on a low temperature and they’ll turn out just the same as letting them dry for 8 hours. As the tracta are drying/baking you can now prepare the beans.

Fabam Vitellianam

To prepare Fabam Vitellianam, Apicius gives us the following information:

“Peas or beans with yolks are made thus: cook the peas, smoothen them; crush pepper, lovage, ginger, and on the condiments put hard-boiled yolks, 3 ounces of honey, also broth, wine, vinegar; mix and place all in a sauce pan; the finely chopped condiments with oil added, put on the stove to be cooked; with this flavor the peas which must be smooth; and if they be too harsh add honey and serve.”

(From: Apicius: Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome. Joseph Dommers Vehling, 1936 and Grainger, 2006)

Working off of the information above was tricky. Apicius must have liked his mulsum too because he forgot to give any indication of weight or volumes except for the honey! Oh well… He can’t be good at everything! The following recipe is what resulted from experimenting with Apicius’ instructions and ingredients for his Vitellian Beans recipe. Here’s what you’re going to need:

Ingredients

- 450 gr (3 cups) of dried fava beans

- 6 large eggs

- 2 cups of unsalted vegetable broth

- 1/2 cup of white wine

- 4 tbsp of vinegar

- 5 tbsp of honey

- 2 tsp of garum (fish sauce)

- 1 tsp of cracked black pepper

- 3 tsp ground ginger

- 1 tsp celery seed or ajwain seed

- olive oil

- 1 tsp of diced fresh coriander (optional, not called for in original recipe)

Step 1. Drain the beans from the water they were soaking in overnight and place them in a pot of fresh water. Boil the beans for 2 hours until they soften and begin to break open.

Step 2. Boil the 6 eggs, cool them, peel them and reserve 6 hard-boiled yolks for the fabam mixture.

Step 3. In a large mixing bowl or in a mixer container, add the cooked beans along with the egg yolks and 1 cup of vegetable broth. Smash the beans thoroughly and mix the broth and egg yolks into the beans making a creamy consistency.

Step 4. In a large pot add in the remaining cup of vegetable broth, wine, vinegar, honey, fish sauce, pepper, ginger, and celery seed and bring to a quick boil. The idea here is to burn off the alcohol in the wine and simmer the spices a bit to infuse all of the flavours together. Turn the heat down as soon as the liquids have boiled.

Step 5. Add the creamed beans and yolks into the heated sauce and stir and reduce for 15 minutes. The mixture may seem like chowder at first but after a few minutes of stirring, the beans and sauce will bind and start to thicken.

Step 6. To prepare the beans and tracta for serving, fill soup bowls with a ladle-full of the warm fabam and break off three or four pieces of tracta that can be placed into the serving bowls themselves. Drizzle the fabam with a few drops of sharp, peppery olive oil and serve. *Optional* You may also wish to garnish the top with a diced Roman herb such as coriander like I have done here. It brings some colour to the presentation and adds a pop of freshness to the warm, earthy flavours of the beans and tracta.

After working on this recipe for almost an entire day, I have to say that the final result was just extraordinary. I am going to highlight a few points here: the fabam recipe contains eggs, vinegar, wine and ginger. Who could possibly imagine that those seemingly opposite flavours could come together with the strong, smoky flavour of celery seed and earthy flavours of beans and create such a complete and flavourful dish? I was absolutely silenced when I took my first bite. I didn’t dare use a spoon to eat the fabam either, and I hope that you do the same. The tracta rusks were strong, chewy and so incredibly tasty. The richness of the whole wheat flavour and the durability of the rusk made me convinced that I could eat anything in my fridge using it as an edible ‘scoop’. The combination of the flavours between the sweet and wholesome farro rusks and the warm, earthy and tangy beans was perfect, absolutely perfect…. and incredibly pleasant. Just as all comfort food should be, Roman or otherwise.

So here’s to woolens, sweaters, home-made soups and breads! Winter is coming and now we’re prepared thanks to Cato and Apicius. Cena Bene and good eating to you!

Please feel free to rate and leave comments or suggestions about this recipe below.

I have a couple of thoughts about the tracta as someone with some experience with artisan baking. First, if you let the dough rest for a while after forming, it will be easier to shape as the gluten has time to relax. Say 20-30 minutes. Second is, I wonder if the dough was originally made and allowed to rest for an even longer time before shaping. I’m thinking of making the dough in the evening, letting it rest over night, and shaping and drying the next day which would allow for some fermentation from natural yeasts, more flavor from the grains, and an easier to handle dough – probably resulting in a thinner rusk, when shaped and dried the next day. That’s the way I’m leaning in trying to make this anyway. I really enjoyed reading this!

Thanks Beth! That’s a great idea. Come back and let us know how that worked out for you! Tracta was a versatile craker/hardtack/pastry dough that was used for a lot of purposes so I certainly hope it would be easier to handle. – Farrell

Thanks for the very descriptive recipes. Especially the tracta. Sometimes seemingly simple recipes are the hardest to figure out!

Do you think that perhaps they would have used garum to flavor up the fabam? That would be my first guess.

I plan to try this recipe soon!

Thanks for pointing this out, Cheryl! I think Vehling may have been hitting the mulsum a bit too hard and missed this ingredient. 😉 Adjusted accordingly. Happy cooking!