The Christmas season is truly a beautiful time of year! You simply cannot beat that ‘cozy vibe’ that envelopes us as the first week of December arrives. Houses and streets twinkling with lights, kids practicing Christmas carols for school pageants, and the same old holiday movies on repeat for days make Christmas one of the most sensory experiences of the year. This warm and fuzzy vibe is a collective sensory experience for those of us who celebrate the holiday: it’s happening all around us, all at once, and generally sees everyone in much better spirits than usual. Within our own homes and families, however, this experience becomes much more personal and meaningful: something that is directly connected to our family, to our faith, to memories of Christmases gone by, and to late family members who have passed on and are missing from the holiday table. It is those of us in the kitchen during the holiday season who are responsible for bringing the memory of late family members back to the holiday table, and we do it with food.

The loss of a family member is never easy, and it takes years to process. Psychologists say that the stages of grief following the loss of a loved one progress through five key steps: denial; anger; bargaining; depression; and acceptance. If it were up to me, I’d add a sixth step: food. For it is certain dishes that are served at family dinners, such as those laid out for Christmas or Thanksgiving, that tether the spirit of our late loved ones to us, with such sensory might, that it’s almost as if they have never left us.

In our family, we make a Jell-O salad every year as part of our Christmas dinner to honour my late grandmother. Some readers will understand why marshmallows, shredded carrots, and pineapple chunks suspended in Jell-O result in a culinary masterpiece that’s like happiness materialized on a platter, while other readers, with less refined palates, will scoff at the dish. But when it’s a dish you’ve been served at the holiday table, year after year, by someone near and dear to you, it becomes something much more than just the dish itself: it becomes a pseudo-visitation by the person who once made it.

Have you ever had an experience when you were out for dinner and a dish was served that, when it hit your palate, sent you reeling on a sensory roller-coaster back to a time and place in your life that was associated with someone that you loved dearly? I have, but I never expected it to happen to me within the sphere of my research. After all, ancient Roman food has nothing to do with my Swedish grandmother and her Ukrainian friends, right?… Wrong.

Recently, during a cooking class that I was teaching at Eataly Los Angeles, I was preparing a simple Roman wheat berry pudding. As I was telling the class about the various uses for cereal grains in ancient Roman meals, I paused for a moment to taste the dish that I was preparing. When I did, I was speechless for a moment as it hit me — plump, chewy, boiled wheat berries kissed with the sweetness of honey and the earthiness of freshly cracked walnuts — and for a few seconds, I was transported back into a single memory: There I was, 10 years old, crammed elbow-to-elbow with my family at my grandmother’s kitchen table as she lays out the dishes that make up our Christmas dinner. On the table is a platter with slices of carved turkey meat, white and dark; green beans almondine; mashed potatoes; a Jell-O salad; turnips Teulon; and large bowl of kutia: a Ukrainian pudding made of boiled wheat berries, honey, poppy seeds and walnuts. My grandmother, who was not of Ukrainian descent, had most likely been taught how to prepare the dish by one of her Ukrainian friends and thought it would make a lovely addition to our Christmas table. And in our family, this dish was strongly associated with her.

Kutia is an Ukrainian Orthodox Christian ceremonial sweet grain pudding that is often served during funerary feasts, following the death of a loved one. It is also prepared during the Ukrainian Orthodox Christmas season. On Ukrainian Christmas Eve (January 6th), family members come together for Sviata Vecheria, or the ‘Holy Supper’, which is comprised of 12 meat- and dairy-free dishes that symbolize the twelve apostles. The first dish of the feast is kutia and it is the last to remain on the table as well. Ukrainian-Canadian home-economist, Savella Stechishin, writes that as the family sits down to eat, the first spoonful of kutia is tossed into the air and offered to departed family members so they may join the living in their holiday feast. The dish is also left on the table throughout the night, complete with serving spoons, so that deceased family members may continue to enjoy the dish.

Sacred wheat berry puddings like kutia are familiar to many central and Eastern European countries and go by similar names, such as: kolivo (Bulgaria), coliva (Romania), kolio (Georgia), and koljivo (Serbia). In Sicily, the dish is known as cuccìa, and in Greece it is called koliva/kolyva: not to be confused with the ancient Greek ‘cakes’ or ‘bread rolls’ referred to as collyra and collabos in the writings of 2nd century Greek grammarian, Athenaeus (Deipnosophistae, 3:110f-111a). Rather, the name of this pudding is likely derived from the ancient Greek words for ‘kernel of grain’ or ‘small coin’: kollyvo or kollybos. This etymological connection draws an even stronger link between the Greek name of the wheat berry pudding (koliva) and its relationship with the dead, especially when Graeco-Roman religious and funerary practices come into play.

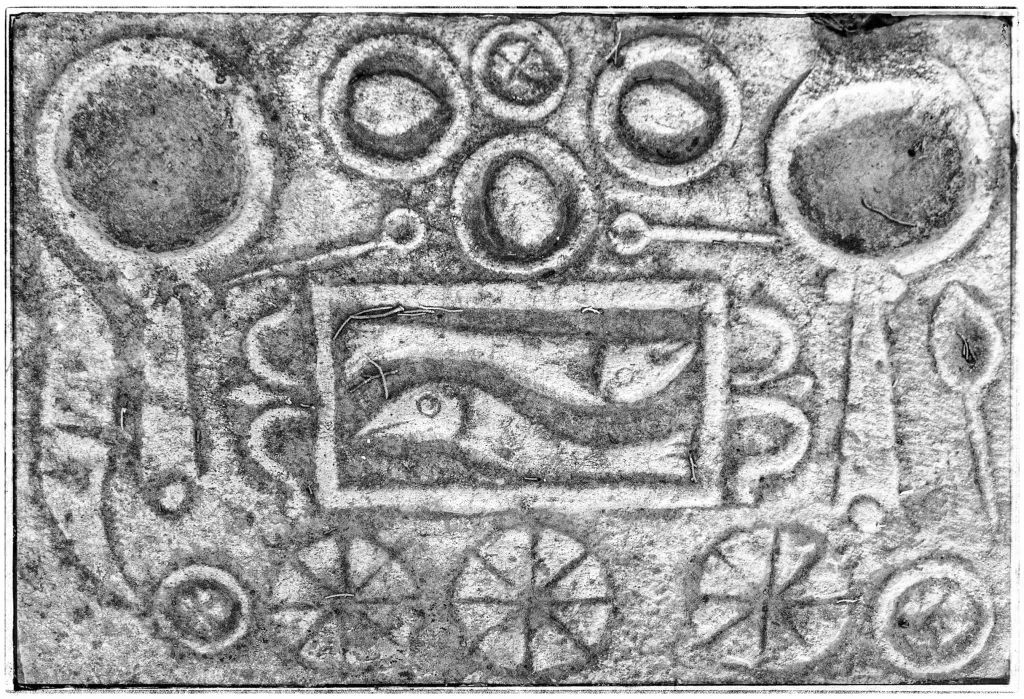

In the 2nd century BC, the Hellenized Syrian satirist, Lucian, writes of the ‘obol of Charon’: the coin placed in the mouth of a deceased person so that the soul may pay the ferryman, Charon, for its passage across the River Styx into the underworld. Archaeological finds also support the Graeco-Roman practice of placing coins with the dead prior to their burial. However, this isn’t the only funerary rite that potentially connects the Orthodox Christian dish koliva to the souls of the dead in a Classical Mediterranean setting: both Greeks and Romans took part in feasting with the dead at their resting places following their burials, even during the months and years that followed. Evidence of this ritual can be seen in bas-relief form on several funerary stelae excavated from the ruins of the 2nd century Roman/early Christian city of Thamugadi (Timgad, Algeria). On the stelae that feature feast scenes, the bases are depicted as tabletops, on which servings of fish, bread, eggs, and other smaller dishes of food are arranged. But was the grain-based koliva an actual dish that was a part of the Thamugadi stelae feast depictions, or a part of funerary feasts of ancient Greece and Rome in general?

A scholion (ancient commentary) to Aristophanes, Acharnians 1076, elaborates that during the wine harvest festival ‘Anthesteria’, a pot of ‘panspermia’ (a mixture of seeds) was sacrificed to Hermes: the Greek god of the underworld and the guide to souls along the road between life and death. The term ‘panspermia‘ is often treated as synonymous with the grain-based pudding, koliva, but the Greek literary record doesn’t support this theory. The Greek poet Alcman (7th c. BC), quoted in Athenaeus (14.173), describes a porridge-like dish called púanion (from púanos: bean), which is comprised of ‘seeds of all sorts’ (panspermia) that have been sweetly stewed. Stewed grains of wheat, however, are differentiated as a dish called: chidron in the same passage. The 2nd century Greek physician, Aretaeus, also refers to another sweet grain dish called Chondrus, which consists of boiled emmer or spelt wheat that is dressed in honey.

In ancient Rome, a stewed wheaten porridge would have been known as tragum or pultem/puls. Roman senator, Cato the Elder (2nd c. BC), describes pultem punicam as a porridge prepared with kernels of grain, honey, cheese and an egg but it is the Roman collection of Apician recipes (De Re Coquinaria, 1st-5th century AD) that puts forth a complete recipe for a sweet, boiled wheaten pudding dish called: Dulcia Piperata (Peppered Sweets) that, like kutia and koliva, contains whole boiled grain, nuts, and honey.

It remains to be seen if dulcia piperata is a Latin synonym or cousin of the Greek koliva, or if the smaller dishes of food on the Thamugadi funerary stelae represent a sweet wheaten pudding being served by the living to the dead. However, if my taste buds and archaeoculinary spidey-senses are to be the judges, I’d say the relationship between the dish that Apicius’ calls dulcia piperata and the earliest ritual forms of koliva is quite strong.

While I was in the midst of tasting dulcia piperata during the class I recently taught, I was indeed taken aback for a moment as the textures and flavours of the dish brought my grandmother and her Christmas cooking to the forefront of my brain, and my mind flooded with questions: How could such a simple dish carry the memory and spirit of someone long departed? Why, in almost all the countries that this dish is prepared in, is it offered to the souls of loved ones who have passed away? How is it that this dish has survived, relatively unchanged, through millennia to end up on holiday tables from Eastern Europe to East Kildonan? Perhaps, just like the Ukrainians, Romanians and Bulgarians of more recent history, the ancient Greeks and Romans before them missed their grandmothers too.

Dulcia Piperata (Peppered Sweets)

Source: Apicius VII:11.4 “Pound pepper; add honey, wine, passum, and rue*. Add to the mixture pine nuts, nuts, and boiled farro. Add chopped roasted hazelnuts and serve.” (Trans. Grocock & Grainger, 2006).

*Rue is a risky ingredient. I do not advise using it.

Ingredients (Yields 4 Servings):

- 200 g (1.5 cups) uncooked farro (can be substituted with wheat or barley grains in a pinch)

- 700 g (3 cups) water

- 85 g (1/4 cup) honey

- 100 g (1/2 cup) Vin Santo (can be substituted with a sweet wine in a pinch)

- 60 g (1/2 cup) pine nuts

- 90 g (1 cup) diced walnuts

- 25 g (1/4 cup) diced hazelnuts

- 5 g (1 tsp) cracked black pepper or grated long pepper

- Optional: Raisins as garnish

Implements:

- Mortar and pestle (or food processor)

- Sharp knife

- Large Mixing Bowl

- Whisk

Preparation:

- Place the farro and water in a pot and bring it to a boil. Reduce element to low and cover for 30 minutes. Strain and cool.

- With a sharp knife (or food processor), dice the walnuts (not too fine).

- With a mortar and pestle (or food processor) finely dice the hazelnuts. Toast the diced hazelnuts on the base of a pan on high for 1 to 2 minutes, until bronze.

- Place the pine nuts and wine in a pot and bring it to a quick boil to evaporate the alcohol. Whisk and reduce to simmer and add the honey and whisk for a minute until the mixture thins.

- Once the boiled farro has cooled, place it into a large mixing bowl and fold in the diced walnuts.

- Pour the wine, honey, and pine nut sauce onto the farro and fold the sauce into the mix until well-blended.

- Let cool to room temperature.

Serving:

Serve the pudding warm or chilled, dusting the top of the pudding with black or grated long pepper and diced hazelnuts prior to serving. The dish can be served family style and spooned onto each plate as a side during the main course.

Optional: Add a tangy pop with a few raisins sprinkled on top. Raisins are not called for in the original recipe but were a common ingredient in ancient Rome and are often featured in modern versions of kutia, koliva and their other Eastern European cousins.

For those who would like to use the dish in a ritual capacity, to honour family who are no longer with you: take a spoonful of grain from the dish before serving it and toss some of it towards the ceiling above the table. When the meal is over, leave the remainder of the dulcia on the table with a spoon so that the souls of your loved ones can partake of the dish with you. May their memory live on at your holiday table and in the dishes that you prepare in their name.

Merry Christmas, from our family to yours.

Did you make this recipe? Share photos and join in the conversation on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.