Hello good readers and Happy New Year to you! Now that we’ve all spent two weeks trying to eat healthy again after the holidays, I trust that everyone is now ready to abandon all New Year’s dietary resolutions and join me for some high-calorie Roman comfort food?…. Good! Because it’s ‘Moretum Week’ here at Tavola Mediterranea. That’s right. Who needs ‘Shark Week’ when you can be inundated by Roman cheese recipes instead, right?! So put down that bowl of kale and come with me, good people. We’re going to explore a calorie-rich Roman cheese ‘salad’ instead and not just one recipe for it, but three. We’re going to be swimming in moretum by the end of ‘Moretum Week’ so check back daily! But before we dive in, let’s have bit of history first…

So, what is Moretum? The word ‘moretum’ translates to ‘salad’ in latin and the dish is represented in the Roman written record, in the Late Republican and Early Imperial periods, as being a simple, vegetarian meal that is made with a base of cheese, additions of herbs and other greens, and condiments like olive oil or vinegar. Moretum is made using a common kitchen implement found throughout the Roman Mediterranean: a mortarium, or a mortar. The ingredients are added into the mortar, one by one, pulverized and minced together with a pestle, and formed into a spread or a dip which can then be consumed with bread.

Mortars were a commonly used kitchen implement in the Classical Mediterranean. They are common in the archaeological record the world over, actually, often found in the form of permanently installed grinding stones, inset floor basins, or free-standing stone or ceramic bowls. Mortars and pestles have been present in the archaeological record since the Paleolithic Period. They were typically formed from stone or ceramic that contained coarse inclusions in the clay, such as pumice or sand, which allowed for a porous working surface with which to grind or pulverize foodstuffs and medicinals. A pestle was used to pound or pulverize ingredients against the porous inner surface of the mortar making these implements the world’s first food processors and highly efficient ones at that. Mortaria, the Roman mortar, were common in Roman kitchens and were used daily for food preparation. Making moretum was just one of the uses for the Roman mortarium.

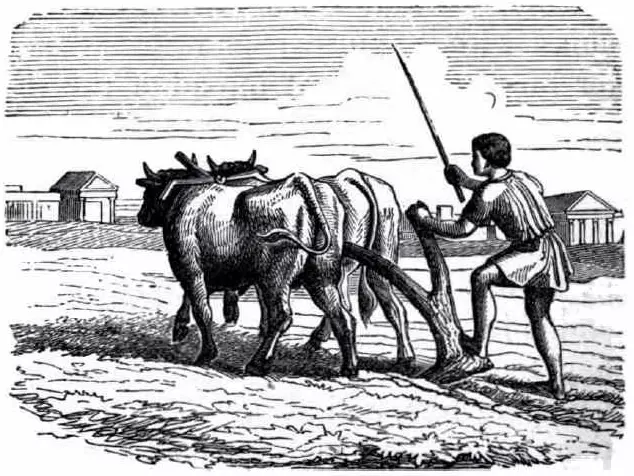

There are several references to moretum in the Classical Roman documentary record: a few references are made in the agricultural writings of Columella (4 BC-70 AD); and one particularly memorable reference is from a poem in the Appendix Vergiliana (1st c. BC). This post’s moretum recipe is derived from this poem in the Appendix Vergiliana titled “Moretum” (The Salad) and it is believed to have been written by Vergil (Virgil) either in its entirety or with some contributions from other poets. If I am to be honest, this poem is one of the most beautiful historical accounts of Roman daily life and diet that I have ever read. It is also a fantastic piece of documentary evidence that serves as a secondary source of information for the interpretation of the archaeological remains of kitchen implements such as mortaria or quern-stones. Vergil’s poem not only tells the story of a lonely peasant ploughman, Symilus, toiling miserably over his breakfast, but the poem also tells us how to make this meal, which kitchen technologies are being used, and how to use them. This document serves many purposes indeed! So, before we proceed to making Symilus’ moretum recipe, why don’t we put the kettle on or grab a cup of coffee and sit down for ten minutes and read this beautiful poem. It paints such an honest and telling picture of what daily plebeian life was like in the agricultural settings of ancient Rome during the Late Republic. It’s worth the read, I promise.

Moretum (The Salad)

by Vergil (Virgil) et al.

Already had the night completed ten

Of winter’s hours, and by his crowing had

The winged sentinel announced the day,

When Symilus the rustic husbandman

Of scanty farm, solicitous about

The coming day’s unpleasant emptiness,

Doth slowly raise the limbs extended on

His pallet low, and doth with anxious hand

Explore the stilly darkness, groping for

The hearth which, being burnt, at length he finds.

I’ th’ burnt-out log a little wood remained,

And ashes hid the glow of embers which

They covered o’er; with lowered face to these

The tilted lamp he places close, and with

A pin the wick in want of moisture out

Doth draw, the feeble flame he rouses up

With frequent puffs of breath. At length, although

With difficulty, having got a light,

He draws away, and shields his light from draughts

With partially encircling hand, and with

A key the doors he opens of the part

Shut off to store his grain, which he surveys.

On th’earth a scanty heap of corn was spread:

From this he for himself doth take as much

As did his measure need to fill it up,

Which ran to close on twice eight pounds in weight

He goes away from here and posts himself

Besides his quern,’ and on a little shelf

Which fixed to it for other uses did

The wall support, he puts his faithful light.

Then from his garment both his arms he frees;

Begirt was he with skin of hairy goat

And with the tail thereof he thoroughly

Doth brush the stones and hopper of the mill.

His hands he then doth summon to the work

And shares it out to each, to serving was

The left directed and the right to th’ toil.

This turns about in tireless circles and

The surface round in rapid motion puts,

And from the rapid thrusting of the stones

The pounded grain is running down. At times

The left relieves its wearied fellow hand,

And interchanges with it turn about.

Thereafter country ditties doth he sing

And solaces his toil with rustic speech,

And meanwhile calls on Scybale to rise.

His solitary housekeeper was she,

Her nationality was African,

And all her figure proves her native land.

Her hair was curly, thick her lips, and dark

Her colour, wide was she across the chest

With hanging breasts, her belly more compressed,

With slender legs and large and spreading foot,

And chaps in lengthy fissures numbed her heels.

He summons her and bids her lay upon

The hearth some logs wherewith to feed the fire,

And boil some chilly water on the flame.

As soon as toil of turning has fulfilled

Its normal end, he with his hand transfers

The copious meal from there into a sieve,

And shakes it. On the grid the refuse stays,

The real corn refined doth sink and by

The holes is filtered. Then immediately

He piles it on a board that’s smooth, and pours

Upon it tepid water, now he brought

Together flour and fluid intermixed,

With hardened hand he turns it o’er and o’er

And having worked the liquid in, the heap

He in the meantime strews with salt, and now

His kneaded work he lifts, and flattens it

With palms of hand to rounded cake, and it

With squares at equal distance pressed doth mark.

From there he takes it to the hearth (ere this

His Scybale had cleaned a fitting place),

And covers it with tiles and heaps the fire

Above. And while Vulcanus, Vesta too,

Perform their parts i’ th’ meantime, Symilus

Is not inactive in the vacant hour,

But other occupation finds himself;

And lest the corn alone may not be found

Acceptable to th’ palate he prepares

Some food which he may add to it. For him

No frame for smoking meat was hung above

The hearth, and backs and sides of bacon cured

With salt were lacking, but a cheese transfixed

By rope of broom through mid-circumference

Was hanging there, an ancient bundle, too,

Of dill together tied. So provident

Our hero makes himself some other wealth.

A garden to the cabin was attached,

Some scanty osiers with the slender rush

And reed perennial defended this;

A scanty space it was, but fertile in

The divers kinds of herbs, and nought to him

Was wanting that a poor man’s use requires;

Sometimes the well-to-do from him so poor

Requested many things. Nor was that work

A model of expense, but one of care:

If ever either rain or festal day

Detained him unemployed within his hut,

If toil of plough by any chance was stopped,

There always was that work of garden plot.

He knew the way to place the various plants,

And out of sight i’ th’ earth to set the seeds,

And how with fitting care to regulate

The neighbouring streams. And here was cabbage, here

Were beets, their foliage extending wide;

And fruitful sorrel, elecampane too

And mallows here were flourishing, and here

Was parsnip,’ leeks indebted to their head

For name, and here as well the poppy cool

And hurtful to the head, and lettuce too,

The pleasing rest at end of noble foods.

[And there the radish sweet doth thrust its points

Well into th’ earth] and there the heavy gourd

Has sunk to earth upon its belly wide.

But this was not the owner’s crop (for who

Than he more straightened is?). The people’s ’twas

And on the stated days a bundle did

He on his shoulder into th’ city bear,

When home he used to come with shoulder light

But pocket heavy, scarcely ever did

He with him bring the city markets’ meat.

The ruddy onion, and a bed of leek

-For cutting, hunger doth for him subdue-,

And cress which screws one’s face with acrid bite,

And endive, and the colewort which recalls

The lagging wish for sexual delights.

On something of the kind reflecting had

He then the garden entered, first when there

With fingers having lightly dug the earth

Away, he garlic roots with fibres thick,

And four of them doth pull; he after that

Desires the parsley’s graceful foliage,

And stiffness-causing rue,’ and, trembling on

Their slender thread, the coriander seeds,

And when he has collected these he comes

And sits him down beside the cheerful fire

And loudly for the mortar asks his wench.

Then singly each o’ th’ garlic heads be strips

From knotty body, and of outer coats

Deprives them, these rejected doth he throw

Away and strews at random on the ground.

The bulb preserved from th’ plant in water doth

He rinse, and throw it into th’ hollow stone.

On these he sprinkles grains of salt, and cheese

Is added, hard from taking up the salt.

Th’ aforesaid herbs he now doth introduce

And with his left hand ‘neath his hairy groin

Supports his garment;’ with his right he first

The reeking garlic with the pestle breaks,

Then everything he equally doth rub

I’ th’ mingled juice. His hand in circles move:

Till by degrees they one by one do lose

Their proper powers, and out of many comes

A single colour, not entirely green

Because the milky fragments this forbid,

Nor showing white as from the milk because

That colour’s altered by so many herbs.

The vapour keen doth oft assail the man’s

Uncovered nostrils, and with face and nose

Retracted doth he curse his early meal;

With back of hand his weeping eyes he oft

Doth wipe, and raging, heaps reviling on

The undeserving smoke. The work advanced:

No longer full of jottings as before,

But steadily the pestle circles smooth

Described. Some drops of olive oil he now

Instils, and pours upon its strength besides

A little of his scanty vinegar,

And mixes once again his handiwork,

And mixed withdraws it: then with fingers twain

Round all the mortar doth he go at last

And into one coherent ball doth bring

The diff’rent portions, that it may the name

And likeness of a finished salad fit.

And Scybale i’ th’ meantime busy too

He lifted out the bread; which, having wiped

His hands, he takes, and having now dispelled,

The fear of hunger, for the day secure,

With pair of leggings Symilus his legs

Encases, and with cap of skin on ‘s head

Beneath the thong-encircled yoke he puts

Th’ obedient bullocks, and upon the fields

He drives, and puts the ploughshare in the ground.

(Source: Appendix Vergiliana at virgil.org)

Now, with those descriptive passages and vivid images of the waking moments of a Roman ploughman fresh in our brains, let us roll up our sleeves and prepare our moretum as Symilus would. We’ll follow along with Symilus but I’ll add in my preparation notes as well. Note: In my preparation of this recipe I followed this poem and Symilus’ actions and ingredients list as closely as I could because I enjoy the immersive aspect of emulating the original process; it helps me to understand the action and the implements better. I used a mortar and pestle to process the moretum, a wood-fired ceramic oven and baking tiles to bake the flatbread, and a manual table-top quern-stone to mill my own flour. It is likely that some readers may not be as nerdy as I am and other readers may simply not have these implements at their disposal so substitutions are suggested and are acceptable in the course of trying this recipe! For those fellow nerds who would like to procure their own mortars, pestles, baking tiles and manual quern-stones, they can be found easily online or at your local cooking supply shops. Some ceramic outdoor ovens are also affordable and easy to assemble!

Symilus’ Aged Goat Cheese and Garlic Moretum with Flatbread

Ingredients

Moretum

- 1 lb of aged goat or sheep cheese (Pecorino, Drunken Goat, for eg.)

- 4 bulbs of fresh garlic (this is not a typo)

- Handful of fresh parsley

- A few leaves of edible rue (or a handful of cicoria/dandelion greens)

- 1 tsp dried dill

- 1/4 tsp of coriander

- 2 tbsp olive oil

- 1 tbsp white wine vinegar

- salt to taste

Implements

- Mortar and Pestle (or a food processor)

Flatbread

- 2 cups of whole emmer wheat grains (or 2 cups of emmer or whole wheat flour)

- 3/4 cup of tepid water

- salt

Implements

- Manual table-top grain mill (optional)

- Sharp knife

- Ceramic tiles (optional)

Preparation

1. Heat your oven. Symilus begins by rising before dawn, stoking his dying fire from the night before, and lighting his oil lamp. He unlocks his grain store cupboard to remove some grain from his scanty supply with which to make his morning meal. He then takes a seat next to his oil lamp, removes his shirt and prepares to mill the grain using a manual quern-stone. During this time he calls to his housekeeper/servant, Scybale, to feed the fire and add logs to the hearth. So we will follow suit by preheating our conventional indoor ovens or starting a fire in our outdoor ovens. Preheat your oven to 350F/175C/Gas Mark 4 – OR – Start the fire in your outdoor wood-fired oven about 4 hours before you start this recipe to allow for a baking environment of approximately 350F/175C. While the oven is heating, prepare the flour for your flatbread.

2. Prepare the dough for the flatbread. Symilus mills his grain at his rotary quern-stone, rotating the handle over and over, alternating between his left hand and his right hand, whilst singing and swearing throughout the process. This I can appreciate fully. I used 2 cups of whole emmer grain to produce 2 ½ cups of fine milled, sieved emmer flour. The yield ratio of grain to flour was approximately 1:1.25 cups once milled. If you are milling your own flour see the video below to see how I did it. It took 30 minutes for me to mill this amount of grain and I too had to switch arms and change my shirt throughout the process as I broke a sweat and nearly threw my back out as well. But it was worth the work because I made 2 ½ cups of my own flour and it was very satisfying work. If you are not milling your own flour you can throw your back out by lifting the bag of emmer or whole wheat flour from your pantry shelf and retrieving 2 cups of flour from it and placing it in a mixing bowl.

3. Knead the dough. Symilus sieves his flour, as I did, to ensure that he has a fine flour to work with and he leaves the middlings behind as refuse. He asks Scybale to boil him some water and then begins to work the flour and warm water together on a board and adds some salt to the dough. I began by adding 1+3/4 cups of flour to 3/4 cup of tepid water in a mixing bowl. I mixed my dough by hand in the bowl and then transferred it onto a cutting board for the kneading process. I reserved ¼ cup of my flour for dusting the dough during the kneading process.

4. Section the dough. Symilus flattens the dough into rounded cakes with his palm and then presses a square/grid mark into the dough creating perforation lines or even sections in the dough. I flattened my dough out, floured it on both sides, and used a sharp knife to section squares of dough that were the same size as the baking tiles that I preheated in my outdoor oven. If using a conventional oven, just flatten and lightly flour the flatbread then cut it into four to six square even portions.

5. Bake the flatbread. You can also grill or fry this flatbread. Symilus takes his flatbread to the fire where Scybale has cleared a space and he places the flatbread on the hearth, covers it in tiles, and then covers the tiles in fire and ash. Symilus bakes his flatbread for an hour and uses this time to prepare the moretum. He must have made thicker cakes than I did and perhaps his baking temperature was lower than mine. I would suggest you bake your flatbread for less than an hour. I burned my first batch so I advise against it especially as it’s a flatbread. I baked my second batch under hot tiles in a wood-fired oven, at 350 F, for no more than 15 minutes. In either baking environment, keep an eye on the flatbreads and wait for them to darken and harden a bit then remove them.

6. Prepare the moretum. Symilus decides to make something else to eat to accompany his bread that is baking in the hearth. He has no means to smoke meat in his hut and also has no salted meat on hand. All he has is a ring of aged cheese and some dried dill. So he exits his hut and goes to his garden where he retrieves four bulbs of garlic, some parsley, rue, and coriander and brings it inside. There, he strips the garlic of their peels, sprinkles them with a bit of salt and begins to smash the cloves in a mortar using a pestle. Then he mixes the pulverized cloves with the cheese. The fumes from the garlic makes his eyes water as he adds vinegar and olive oil into the mix. As he mixes all of the ingredients together it is noted that the moretum is neither all white nor all green as the cheese and herbs mixed together create a shade that is representative of all of the ingredients combined. The vapour of garlic is strong as Symilus uses his fingers to scoop the cheese salad out of the bowl of the mortar forming a ball of the finished mixture. He removes the flatbread from the hearth, dusts off the ash on the exterior of it, and settles down to eat his meal staving off hunger for one more day. He then starts his day ploughing the fields. We can pretty much follow along with Symilus’ preparation of the moretum. I pulverized the garlic in my mortar, added the cheese, coriander and dill. A rotary motion works well for greens in a mortar but don’t be afraid to use the pestle head to smash garlic or break up cheese. Then I pulverized some cicoria (I did not have rue), parsley and added it in with the cheese and garlic. My mortar bowl is small so I pulverized in batches and mixed everything together in a seperate bowl. I then added the olive oil, vinegar and salt (to taste) and rolled the finished mixture into a firm ball ready for serving along with the flat bread.

When this meal was finally ready I felt that I had fully earned it. So much blood, sweat and tears went into it that by the time it was done, I was famished! The finished moretum was something so foreign and incredible to me. I was amazed at how good that much garlic tastes. Don’t get me wrong… it’s pungent and powerful. You’ll be thrown out of your house after eating this, or you’ll get the bed to yourself that night at the very least. But it tastes good. REALLY GOOD. There’s some heat to it but the cheese softens the blow a bit and holds it all together. The flatbread is a nice, sweet, hearty moretum delivery method that ompletes the whole flavour profile of the dish perfectly.

This moretum recipe was really surprisingly tasty but this was not the only highlight of the recipe for me. The best part of this recipe for me was the labour that went into making it and the appreciation that I gained for the work and time that went into preparing even the most basic of meals in ancient Rome. After 30 minutes of milling grain my lower back, wrists and triceps were sore. My hands were also trembling. Then I had to move on to smashing garlic cloves and breaking up cheese and I was already tired! It took almost an hour of constant physical labour to make this meal and I can appreciate why old Symilus was cursing his life as he worked away on his breakfast. It was HARD WORK to make this meal but when it was finally ready, I was proud of my work and I valued the meal that I made greatly… just as Symilus did, I’m sure. And what a beautiful and unusual guideline to work with for this recipe: poetry. I think I’ll be reading more Vergil going forward, how about you?

Did you try this recipe at home? If so, please feel free to leave comments or suggestions below. You can also join the conversation and share photos on the Tavola Mediterranea Facebook page or Instagram page.

I finally found a greengrocery selling wet garlic (as in, with the outer skins still fresh, not dried to be papery) and bought some to make this cheese again. I reckoned it had to be closer to the original, as Symilus’s garlic is fresh out of the ground. And it’s really delicious – wet garlic, like fresh ginger, has aromatic flavours that it loses when it dries, retaining only its pungency. Highly recommended.

Do you have a recipe book for sale with all of these recipes?

It’s in the works, Jeri! Sit tight…

I’d love one too, haha